To the Editor:

Cocaine has been used by 2.6% of the Spanish population aged between 15 and 64 at some point in their life, making it one of the most consumed illegal drugs after cannabis.1 Cocaine use is associated with multiple complications: neurological, cardiovascular, psychiatric, pulmonary, gastrointestinal and nephrological.

Renal complications associated with cocaine use have received little attention, despite the existence of several mechanisms, in addition to secondary high blood pressure, that can cause acute renal failure (ARF) or worsen a pre-existing case of chronic renal failure.2

Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis (DIAIN) represents a high percentage of acute renal failure in clinical practice. Some studies indicate that DIAIN is the lesion responsible for renal failure in about 15% of biopsies with ARF. Furthermore, in many cases of DIAIN, no biopsy is performed and diagnosis is based on clinical data and recent administration of a new drug which, as described below, is sometimes not very easy to identify.3-5

CASE REPORT

28-year-old male, admitted with pain at the dimples of Venus, fatigue and nausea, with preserved diuresis.

The patient had used intranasal cocaine (1g) five days before admission. He denied having taken non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other medication. The physical examination showed a good general condition, with slightly high blood pressure of 147/97mmHg and without fever, rash or arthralgia.

Cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft, depressible and painless and the liver was palpable 1cm below the costal margin and there was slight pain on bilateral palpation of lower back.

The initial blood test showed an unremarkable complete blood count (without eosinophilia), normal liver function and albumin within the normal range, serum creatinine: 160μmol/l, urea: 7.5mmol/l, potassium: 3.9mmol/l, sodium: 139mmol/l chloride 101mmol/l. Total creatine phosphokinase was normal (3.3μkat/l) with normal MB fraction. Urine sediment showed 2 leukocytes and 3 erythrocytes per high power field and no dysmorphic erythrocytes or eosinophils. Urine biochemistry: sodium: 46mmol/l, potassium: 33mmol/l and chloride: 63mmol/l, protein ratio: creatinine 5g/mol, negative urine culture.

Protein electrophoresis, immunoglobulins, complement, levels of angiotensin converting enzyme and antinuclear antibody titres were normal. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis A, B, and C and mycoplasma did not detect active infection. The ultrasound showed normal-sized, diffusely echogenic kidneys with appropriate arterial and venous flow.

The electrocardiogram was normal. The chest x-ray showed a cardiothoracic ratio <0.5 and lung fields without infiltrates.

After admission, urinary output remained at 50 to 75ml/h and creatinine remained unchanged. The patient underwent a renal biopsy.

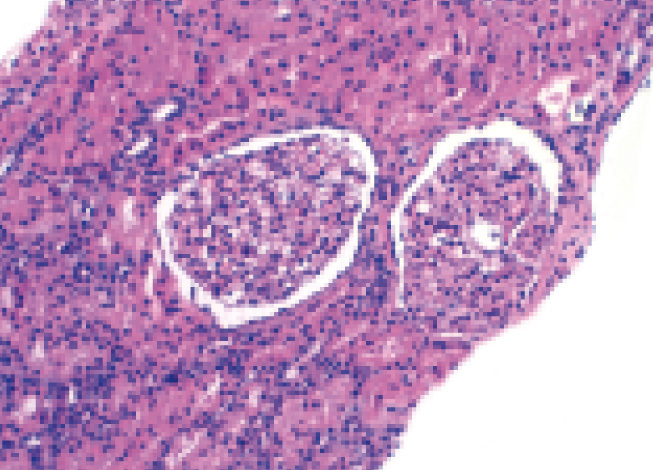

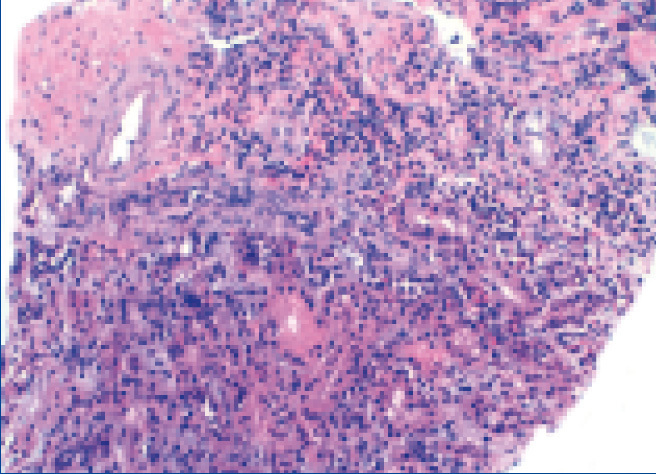

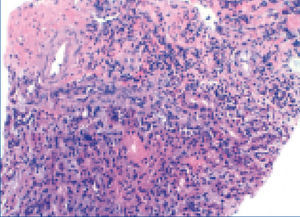

Histological findings are as follows: optical microscopy showed a total of 13 glomeruli, all normal, without sclerosis, proliferation or necrotic lesions (Figure 1). Basement membranes and the glomerular mesangium were normal. The interstitium displayed moderate mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate with abundant eosinophils (Figure 2), with presence of focal tubulitis and atrophy (Figure 2). The arterioles did not display remarkable lesions and immune deposits were not shown in the immunofluorescence.

The findings were compatible with the pathological diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATN).

This fact, along with the clinical characteristics and recent use of cocaine led us to define this case as cocaine-induced AIN.

The patient obviously suspended drug use and was treated with oral prednisone (initial dose 1mg/kg/day), which was progressively decreased and discontinued after 12 weeks.

In the subsequent follow-up, his progression was good with a gradual improvement in renal function until complete recovery in the month in which treatment started.

DISCUSSION

We report the case of a patient with ARF, with acute tubulointerstitial lesion associated with DIAIN, in which no related agent was identified, except for cocaine. Currently people are starting to become aware of cocaine-induced ARF in adults; in fact, the two most common causes are rhabdomyolysis and malignant high blood pressure induced by intense arterial vasoconstriction.

There are few reported cases of cocaine-related DIAIN.2,6 The mechanism remains unclear, and it remains to be demonstrated whether this entity is related to cocaine per se or natural impurities, adulterants or diluents.7 In fact, in the case of crack, contamination is highly likely.

In this case the patient may have been sensitised to cocaine or its additives by previous consumption. Hypersensitivity to the drug is the most likely cause in our patient.7,8

Our patient did not have any “classic” symptoms of ARF, such as fever, rash, or eosinophilia, but recent studies suggest that AIN is a heterogeneous disorder and, therefore, these “classic” symptoms are only seen in fewer than 30% of cases.8 Eosinophiluria is usually interpreted as a feature of DIAIN; however, it has very low sensitivity (67%). The eosinophiluria specificity for the diagnosis of AIN is 87%, but it may be present in other diseases that may also present with acute renal failure.6

The pathogenesis of AIN involves an idiosyncratic allergic reaction to drug exposure. It often involves a type IV hypersensitivity T cell response. Molecular mimicry or direct binding of the drug to the tubular basement membrane are the main mechanisms involved,9 and this maybe the underlying process in our case.

Early recognition of DIAIN is crucial because patients may ultimately develop chronic kidney disease.

The key element of treatment is the interruption of the causative agent. However, as DIAIN is an inflammatory allergic process, it is necessary to consider the use of immunosuppressive agents, including corticosteroids.10

In corticoresistant AIN, there are reports of cases that suggest the benefit of cyclophosphamide and cyclosporine, as well as potential beneficial effects of mycophenolate mofetil.11

Growing evidence based on different studies suggests that steroids lead to a quicker and more complete recovery of renal function.4

As a consequence of interstitial infiltration typical of AIN, a rapid progression towards interstitial fibrosis can occur in a few weeks. Based on these data, we used corticosteroids at the time of diagnosis to prevent potential progression to irreversible interstitial fibrosis. The result was positive and displayed rapid normalisation of renal function.

DIAIN should be recognised as a potential cause of acute renal failure in cocaine users and the history of potential use should be carefully investigated in patients with AIN with no obvious cause.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Renal biopsy.

Figure 2. Renal biopsy.