C1q nephropathy is a controversial disease as some authors consider it to be indistinguishable from minimal change disease (MCD), while others believe it is a between minimal changes and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).1,2 The criteria for diagnosis of the disease include predominant C1q deposits by immunofluorescence and no clinical or laboratory evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus.3,4 Microscopically, in contrast to lupus, there should be no tubulointerstitial disease in C1q nephropathy.5,6

We present a case of a 21-year-old patient, referred to Nephrology from the Paediatric Department in March 2010, when he was 14 years old, due to steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Paediatricians had previously been diagnosed the patient as a likely case of minimal change disease, and treatment was started with corticosteroids at a dose of 80mg/day.

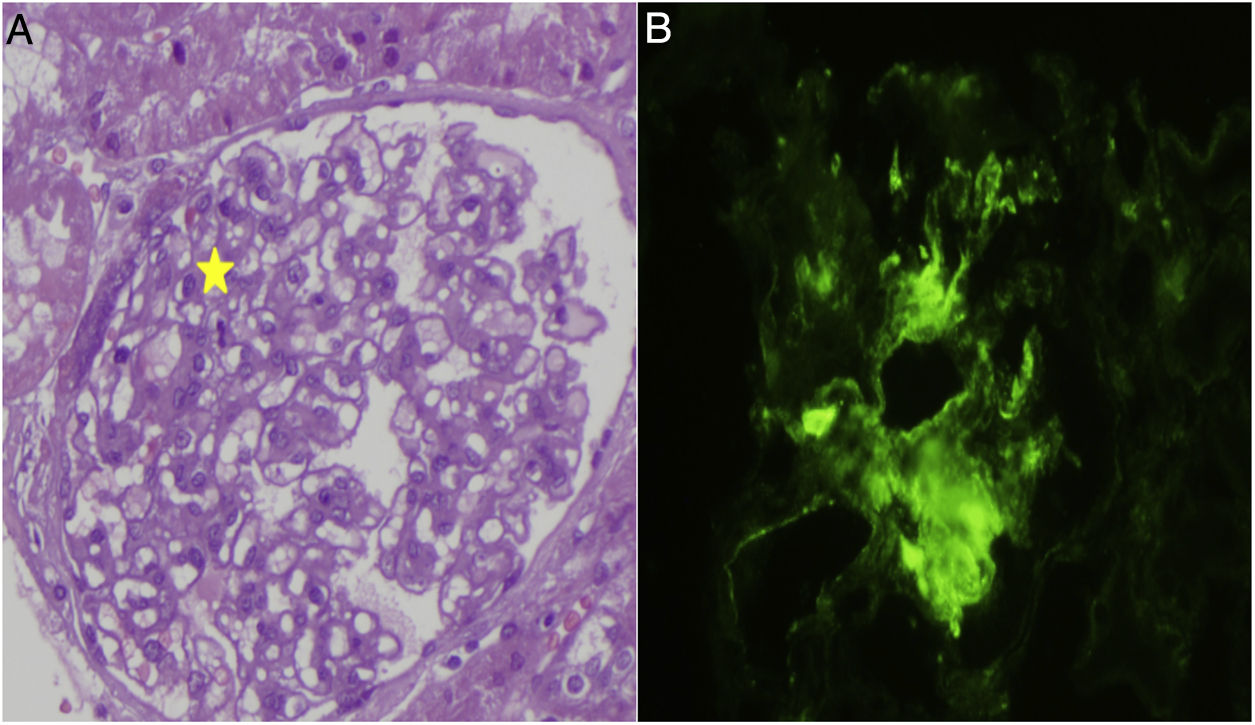

The first visit to Nephrology revealed the following values: albumin 2g/dl; total protein 4.9g/dl; haemoglobin 15.9g/dl; creatinine 0.18mg/dl and electrolytes were normal. Proteinuria was 4.9g in 24h, and C3 and C4 levels were, 162 and 22.9mg/g. An ultrasound revealed that both kidneys were enlarged with increased renal parenchyma related to the nephrotic syndrome. It was decided to maintain steroid treatment and the patient was seen in clinic in January 2011; then, proteinuria was increased despite treatment. The immunological study was negative for ANA, ANCA, ENA, DNA, anti-cardiolipin antibodies and GBM antibodies. Immunoglobulins: IgG 135mg/dl and the rest of immunoglobulins were within normal range. No data indicating anaemia were observed and kidney function remained normal. It was decided to perform a kidney biopsy (Fig. 1): 30 glomeruli, with a slight increase in mesangial cells; no evidence of basement membrane thickening or spikes, and matrix clusters or capillary collapses were not observed. There were no abnormalities in the vascular and tubular components. A dense mesangial C1q deposit was observed on direct immunofluorescence, while a more limited quantity of deposits of C3 and IgG were observed. It was negative for the remaining immunoglobulins, light chains and fibrinogen. Diagnosis: minimal change disease with predominant C1q deposit, compatible with C1q nephropathy.

Treatment was initiated with tacrolimus to maintain levels between 6 and 8μg/l and genetic testing was ordered to rule out diseases related to the WT1 gene (WAGR syndrome, Denys-Drash syndrome and Fraser syndrome). They were all negative and there was no response to the treatment. In February 2012 the patient was started on mycophenolate mofetil with increasing doses up to a maximum of 1g/12h, and again without response. He presented in January 2015 with proteinuria of 9.4g/24h and impaired kidney function, negative autoimmune testing (ANA, ANCA, DNA, ENA, GBM and cryoglobulins). A second biopsy was indicated: 19 glomeruli, of which 50% (9) were completely sclerosed, six did not present abnormalities and the remaining four presented variable degrees of sclerosis, in two glomeruli the slclerosis was also surrounded the Bowman's capsule. Immunofluorescence did not reveal deposits of complement, immunoglobulins, light chains or fibrinogen were observed in any of the structures. Despite the disappearance of C1q deposits in this biopsy, the patient underwent five years of treatment with a progressive decline in kidney function. It was therefore decided to start a fourth line of treatment with rituximab, receiving four weekly boluses in June 2015 with no improvement in proteinuria and significantly impairment of kidney function (Table 1). All possible treatment lines had therefore been exhausted and the patient's status progressed to advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).

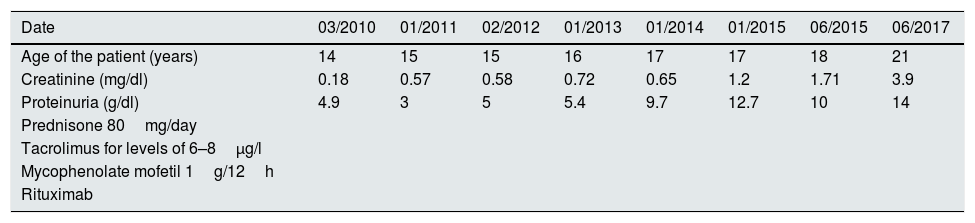

Relationship between treatment, proteinuria and kidney function from March 2010 to July 2017 in a patient with a diagnosis of C1q nephropathy.

| Date | 03/2010 | 01/2011 | 02/2012 | 01/2013 | 01/2014 | 01/2015 | 06/2015 | 06/2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the patient (years) | 14 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 21 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.18 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 1.2 | 1.71 | 3.9 |

| Proteinuria (g/dl) | 4.9 | 3 | 5 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 12.7 | 10 | 14 |

| Prednisone 80mg/day | ||||||||

| Tacrolimus for levels of 6–8μg/l | ||||||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil 1g/12h | ||||||||

| Rituximab |

Over time, and according to the kidney disease stage, the patient received treatment with: acetylsalicylic acid, hidroferol 0.266μg, statins, proton-pump inhibitors, phosphate binders and antihypertensive drugs.

Anti-C1q antibodies target the first complement component. The majority of them are of the IgG subtype, predominantly IgG1 and IgG2, demonstrating a strong correlation between their presence and kidney damage. The mechanisms through which C1q is found in kidney biopsies would be: (1) that it is bound to the Fc portion of the implanted Ig or of the circulating immune complexes; (2) apoptotic remains could capture C1q facilitating their clearance; (3) C1q could bind to C-reactive protein, amyloid or Ig trapped in the glomerulus; (4) specific and direct binding of C1q to renal parenchyma cells; (5) passive entrapment, and (6) cross-reaction with antigens similar to C1q.1,7–9 This therefore explains why every time we are faced with nephropathy involving the classical complement pathway, C1q deposits can be observed in the biopsy.

Therefore, patients who have C1q nephropathy and FSGS are more likely to progress to end-stage kidney disease. There are no randomised trials which have evaluated the treatment of C1q nephropathy. Therapy involves treatment of the underlying microscopic lesion.

Please cite this article as: Romaniouk Jakovler I, Mouzo Javier R, Perez Nieto C, Romero A, Simal F, Castañon B. Enfermedad de cambios mínimos compatible con nefropatía C1q en paciente pediátrico. Evolución y tratamiento de una enfermedad complicada. Nefrologia. 2019;39:84–86.