Chronic hyperkalemia has negative consequences in the medium and long term, and determines the suspension of nephro and cardioprotective drugs, such as renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi). There is an alternative to the suspension or dose reduction of these treatments: the administration of potassium chelators. The aim of this study is to estimate the economic impact of the use of patiromer in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or heart failure (HF) and hyperkalemia in Spain.

Materials and methodThe annual economic impact of the use of patiromer has been estimated from the perspective of the Spanish society. Two scenarios were compared: patients with CKD or HF and hyperkalemia treated with and without patiromer. The costs have been updated to 2020 euros, using the Health Consumer Price Index. Direct healthcare costs related to the use of resources (treatment with RAASi, CKD progression, cardiovascular events and hospitalization due to hyperkalemia), direct non-healthcare costs (informal care: costs derived from time dedicated by patient’s relatives), the indirect costs (productivity loss), as well as an intangible cost (due to premature mortality) were considered. A deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed to validate the robustness of the study results.

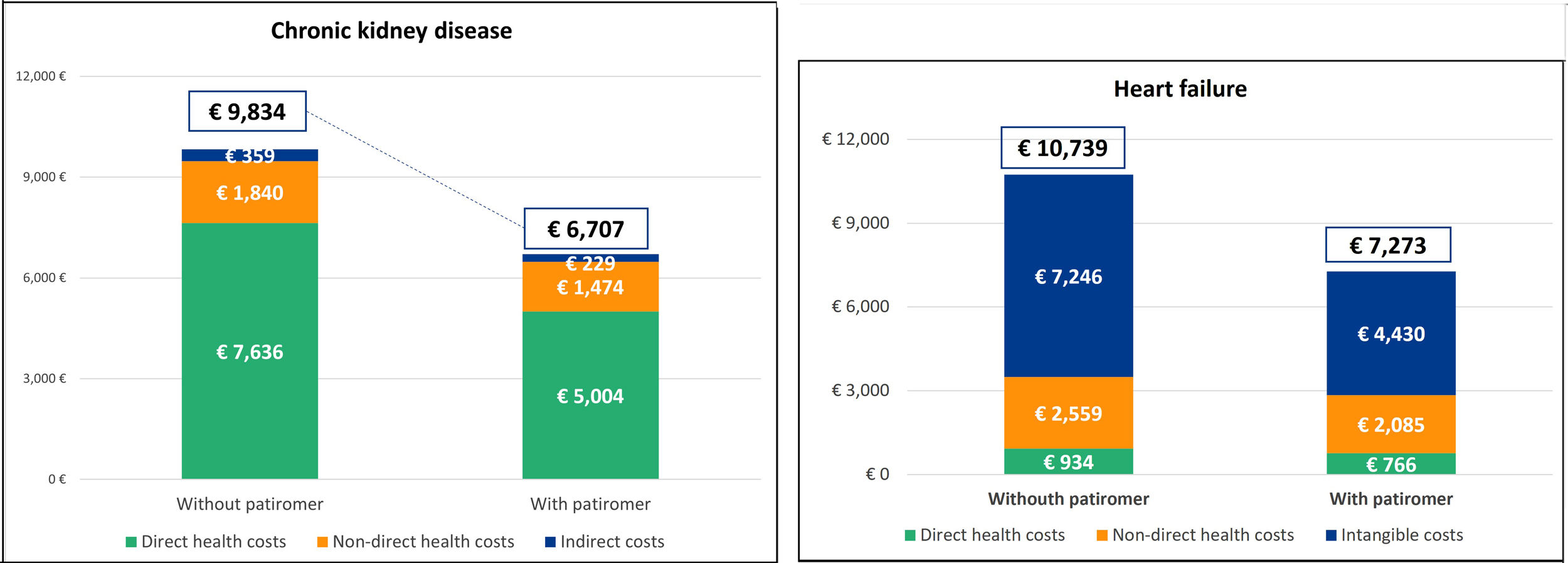

ResultsThe mean annual cost per patient in the scenario without patiromer is €9,834.09 and €10,739.37 in CKD and HF, respectively. The use of patiromer would lead to cost savings of over 30% in both diseases. The greatest savings in CKD come from the delay in the progression of CKD. While in the case of HF, 80.1% of these savings come from premature mortality reduction. The sensitivity analyses carried out show the robustness of the results, obtaining savings in all cases.

ConclusionsThe incorporation of patiromer allows better control of hyperkalemia and, as a consequence, maintain treatment with RAASi in patients with CKD or HF. This would generate a 32% of annual savings in Spain (€3,127 in CKD; €3,466 in HF). The results support the positive contribution of patiromer to health cost in patients with only CKD or in patients with only HF.

La hiperpotasemia crónica tiene consecuencias negativas a medio y largo plazo, condicionando generalmente la suspensión de fármacos nefro y cardioprotectores, en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) e insuficiencia cardíaca (IC), como son los inhibidores del sistema renina-angiotensina-aldosterona. Existe una alternativa a la suspensión o reducción de dosis de estos tratamientos y es la administración de quelantes del potasio. El objetivo de este estudio es estimar el impacto económico que supondría el uso de patiromer en pacientes con ERC o IC e hiperpotasemia en España.

Material y métodosSe ha estimado el impacto económico anual del uso de patiromer desde la perspectiva de la sociedad española, comparando 2 escenarios: pacientes con ERC o IC e hiperpotasemia tratada con patiromer y sin patiromer. Los costes se han actualizado a euros de 2020, utilizando el índice de precios de consumo de Sanidad. Se han considerado los costes directos sanitarios relacionados con el uso de recursos (el tratamiento con inhibidores del sistema renina-angiotensina-aldosterona, la progresión de la ERC, los eventos cardiovasculares y la hospitalización por hiperpotasemia), los costes directos no sanitarios (cuidados informales: costes derivados del tiempo de dedicación por parte de los familiares del paciente), los costes indirectos (pérdidas de productividad laboral), así como un coste intangible (por mortalidad prematura). Se realizó un análisis de sensibilidad determinístico para validar la consistencia de los resultados del estudio.

ResultadosEl coste medio anual por paciente en el escenario sin patiromer es de 9.834,09 y 10.739,37 € en ERC e IC, respectivamente. El uso de patiromer supondría un ahorro de costes superior al 30% en ambas enfermedades. En el caso de la ERC, el mayor ahorro procede del retraso de la progresión de la ERC. Mientras que en IC el 80,1% de estos ahorros provienen de la reducción de la mortalidad prematura. Los análisis de sensibilidad realizados muestran la consistencia de los resultados, obteniendo ahorros en todos los casos.

ConclusionesLa incorporación de patiromer permite controlar la hiperpotasemia y, como consecuencia, mantener el tratamiento con inhibidores del sistema renina-angiotensina-aldosterona en los pacientes con ERC o IC, generando unos ahorros anuales en España del 32% (3.127 € en ERC; 3.466 € en IC). Estos resultados apoyan la contribución positiva que patiromer puede tener tanto en los pacientes con ERC como en aquellos que solo tienen IC.

Hyperkalemia is a common ionic disorder defined as an elevation of plasma potassium evels above 5 mEq/l.1,2 It is classified as mild (5–5.4 mEq/l), moderate (5.5–6 mEq/l) or severe (>6 mEq/l).2 It is caused by reduced urinary excretion of potassium, the use of drugs that affect potassium homeostasis (such as renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system [RAAS] inhibitors) or by the outflow of potassium from the intracellular space in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state3 among others. Hyperkalemia occurs more frequently in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), heart failure (HF), arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus.4 A patient is considered to have chronic/recurrent hyperkalemia if the potassium levels are elevated at least twice per year.1

The prevalence of hyperkalemia in the general population varies between 2.3% and 3.2%.5,6 In Spain, a severe hyperkalemia prevalence of 0.6% has been reported in 39,501 hospitalized patients.7 In patients over 55 years of age with at least one pathology (chronic HF, CKD, ischemic heart disease, arterial hypertension, or diabetes mellitus), the prevalence of hyperkalemia has been estimated at 1.8%–2.6%. In patients with CKD, the prevalence of hyperkalemia reaches 26%,8 and it is higher as the disease progresses to more advanced stages.9 In patients with stage 5 CKD, hyperkalemia prevalences have been reported to be 16.4% of patients on hemodialysis and in 10.6% on peritoneal dialysis.10 It has also been observed that, in CKD stages 4–5, hyperkalemia is more frequent in patients treated with RAAS inhibotors.11 Moreover, the prevalence of hyperkalemia in HF patients reaches 22%.8 One in 30 patients with reduced ejection fraction has hyperkalemia. In addition, 14,900 patients with reduced ejection fraction develop hyperkalemia annually.12

Chronic hyperkalemia has negative consequences in the medium and long term and patients may need to discontinue cardio- and nephroprotective drugs, such as RAAS inhibitors.4 This may reduce the risk of hyperkalemia, but also worsen the prognosis of the disease and increase mortality.13 The mortality rate of patients who discontinue RAAS inhibitors treatment or receive doses below the target is twice that of those using the target dose.13 However, potassium binders allows these treatments to be maintained. Currently, 2 new potassium binders are available: patiromer,14 marketed in Spain since 2019, whose efficacy and safety has been demonstrated in clinical trials15–18; and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate,14 marketed in Spain since 2021, with efficacy and safety also demonstrated in clinical trials.19–22

The aim of this study is to estimate the annual economic impact for the National Health System (NHS) and Spanish society required to maintain of good control of hyperkalemia in patients with CKD or HF with patiromer treatment.

Material and methodsWe estimated the economic impact per patient of treatment with patiromer in patients with HF and CKD at risk of chronic hyperkalemia, considering 2 scenarios: patients with patiromer and without patiromer. A time horizon of one year and a social perspective were applied.

Given that treatment with patiromer allows 94% of patients to continue RAAS inhibitors,15 this percentage of use was assumed in the patiromer scenario. In the non-patiromer arm, since studies indicate that the morbidity and mortality risk due to dose reduction or discontinuation of RAAS inhibitors due to hyperkalemia is very similar,13,23–25 we assumed that all patients would discontinue this treatment.

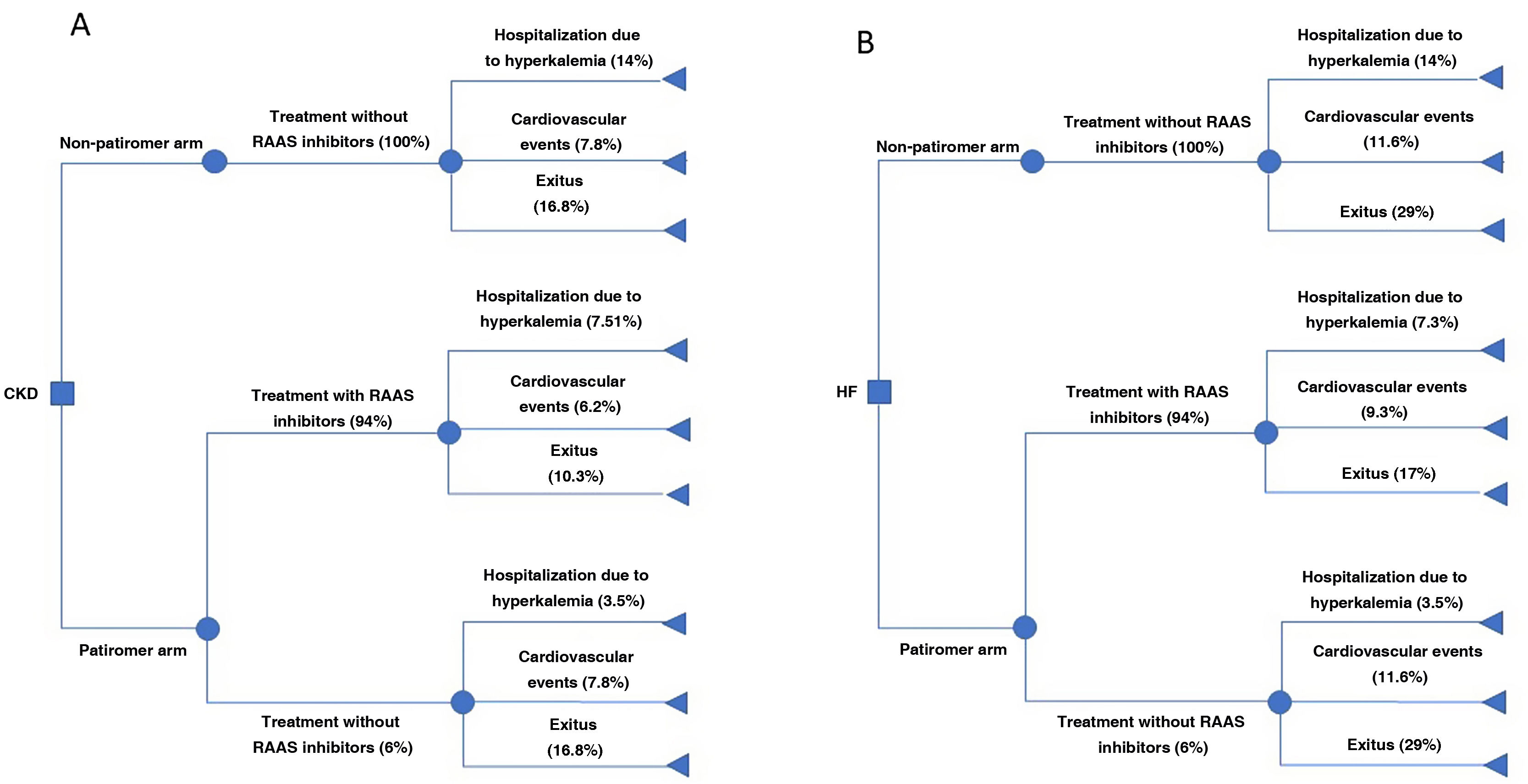

Risk of eventsPatients with CKD may be hospitalized for chronic hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events or disease progression, whereas patients with HF may be hospitalized for chronic hyperkalemia, have cardiovascular events, or suffer an exitus. The risk of suffering such events according to the scenarios of the analysis is shown in Fig. 1. Patients with CKD or HF have a hospitalization risk for hyperkalemia of 14%.26 This risk increases 2.07-fold with the use of RAAS inhibitors, 2.16-fold with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatments, and 1.89-fold with angiotensin II receptor antagonists.27 However, treatment with patiromer reduces the risk of hospitalization by 75%.15

The annual risk of cardiovascular events is 7.8%27 and 11.6%25 in patients with CKD and HF, respectively. Treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by 18% and 24%, respectively.27 Thus, considering the percentage of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (62.07% [HF] and 67.31% [CKD]) and angiotensin II receptor antagonists (27.59% [HF] and 32.01% [CKD]),25,28 we estimate that the use of RAAS inhibitors reduces the annual risk of suffering such events by 20% (RR = 0.80).

In addition, the annual risk of CKD progression is 16.8%29 and thetreatment with RAAS inhibitors reduces this risk by 38%.27 In patients with HF, the risk of mortality at 6 months is 17%. Discontinuation of RAAS inhibitors treatment increases risk of mortality (HR: 1.705).30

CostsThe costs included in the analysis were: direct health care, direct non-health care, indirect costs and intangible costs. The costs were expressed in 2020 euros, and for this purpose the necessary costs were updated using the Health Consumer Price Index.31

Direct health care costsThe direct health care costs included were pharmacological treatments with RAAS inhibitors and hospitalization for chronic hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events. In CKD, we also considered the cost of disease progression.

- 1)

Treatment costs

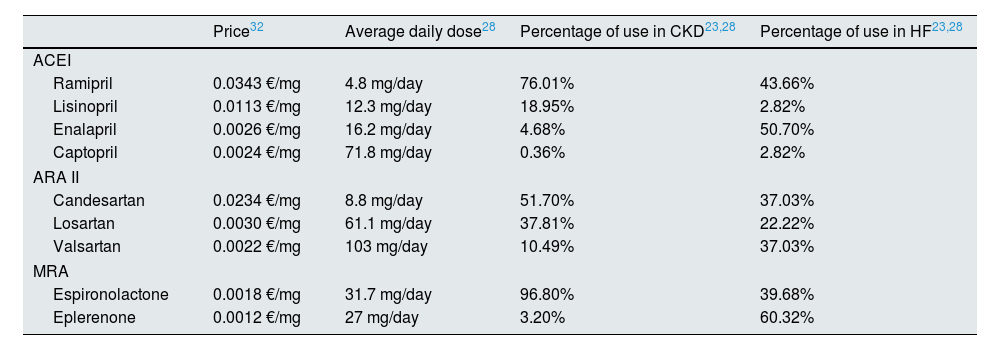

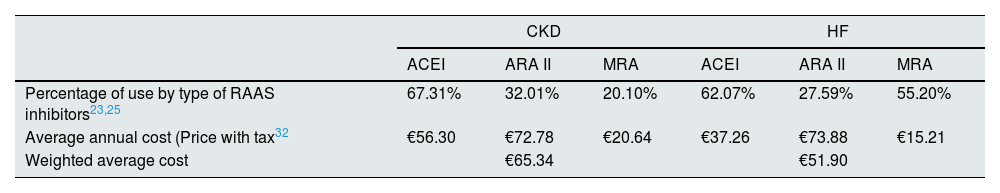

The annual costs of RAAS inhibitorss, available in community drugstores, were calculated using the retail price plus sales tax,32 the average daily dose28 and the distribution of the different treatments (Table 1).23,28 The mean annual cost of the RAAS inhibitors (Table 2) was estimated at €65.34 and €51.90 in patients with CKD and HF, respectively.

- 2)

Hospitalization costs for chronic hyperkalemia

Unit price, average dose, and percentage of use of RAAS inhibitors.

| Price32 | Average daily dose28 | Percentage of use in CKD23,28 | Percentage of use in HF23,28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI | ||||

| Ramipril | 0.0343 €/mg | 4.8 mg/day | 76.01% | 43.66% |

| Lisinopril | 0.0113 €/mg | 12.3 mg/day | 18.95% | 2.82% |

| Enalapril | 0.0026 €/mg | 16.2 mg/day | 4.68% | 50.70% |

| Captopril | 0.0024 €/mg | 71.8 mg/day | 0.36% | 2.82% |

| ARA II | ||||

| Candesartan | 0.0234 €/mg | 8.8 mg/day | 51.70% | 37.03% |

| Losartan | 0.0030 €/mg | 61.1 mg/day | 37.81% | 22.22% |

| Valsartan | 0.0022 €/mg | 103 mg/day | 10.49% | 37.03% |

| MRA | ||||

| Espironolactone | 0.0018 €/mg | 31.7 mg/day | 96.80% | 39.68% |

| Eplerenone | 0.0012 €/mg | 27 mg/day | 3.20% | 60.32% |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARA II, angioten II receptor antagonist; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; Price, retail price plus sales tax; RAAS inhibitors, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors.

Percentage of use and average annual cost of treatments by type of RAAS inhibitor.

| CKD | HF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI | ARA II | MRA | ACEI | ARA II | MRA | |

| Percentage of use by type of RAAS inhibitors23,25 | 67.31% | 32.01% | 20.10% | 62.07% | 27.59% | 55.20% |

| Average annual cost (Price with tax32 | €56.30 | €72.78 | €20.64 | €37.26 | €73.88 | €15.21 |

| Weighted average cost | €65.34 | €51.90 | ||||

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARA II, angioten II receptor antagonist; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; Price, retail price plus sales tax; RAAS inhibitors, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors.

Considering the annual cost of hospitalization of €1,183.1633 and the annual risks of hospitalization due to hyperkalemia, we obtained annual costs of €91.25 and €165.64 in the scenarios with and without patiromer respectively.

- 3)

Costs of cardiovascular events

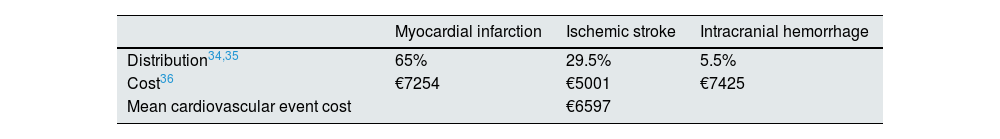

The cost of the different cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage34,35 was assumed according to the average hospitalization costs indicated by the Ministry of Health (ICD10: I21, I61 and I63),36 resulting in a weighted average cost of cardiovascular events of €6,597.42 (Table 3).

The annual direct health care costs of cardiovascular events for patients with CKD or HF were calculated by applying the annual cost and the annual risks of suffering a cardiovascular event, resulting in: €410.64 in patients with RAAS inhibitors and €512.06 in patients without RAAS inhibitors, in CKD; and €616.63 in patients with RAAS inhibitors and €768.08 in patients without RAAS inhibitors in patients with HF.

- 4)

Costs of chronic kidney disease progression

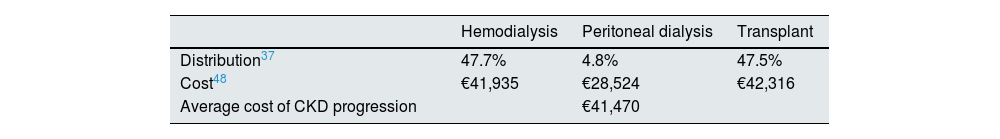

The progression of CKD could imply the need for hemodialysis (47.7%), peritoneal dialysis (4.8%) or transplantation (47.5%)37 with very high costs (Table 4). The average weighted cost in the first year after progression would amount to €41,470. Therefore, the average annual direct health care cost of CKD progression in patients treated with and without RAAS inhibitors amounts to €4282.10 and €6958.06, respectively.

Direct non-health costsThe direct non-health care costs included were informal care (care provided by persons belonging to the cared-for person’s affective environment, usually family members, sometimes also friends or neighbors). Cardiovascular events and the progression of CKD increase patients’ need for this care. Care derived from a cardiovascular event involves an average annual cost of €21,983.84 per patient.38

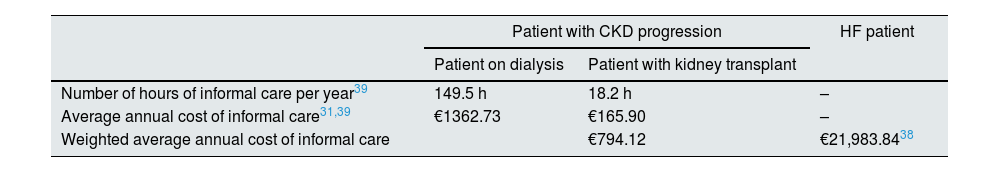

The costs of informal care related to the progression of CKD were estimated by multiplying the number of hours of care needed for dialysis or kidney transplant patients39 by the cost per hour. The hourly cost (€9.12) was estimated from the average salary of health and care workers31 and the number of effective weekly hours worked31 (Table 5).

Weighted average annual cost of informal care for patients with disease progression (CKD or HF).

| Patient with CKD progression | HF patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient on dialysis | Patient with kidney transplant | ||

| Number of hours of informal care per year39 | 149.5 h | 18.2 h | – |

| Average annual cost of informal care31,39 | €1362.73 | €165.90 | – |

| Weighted average annual cost of informal care | €794.12 | €21,983.8438 | |

CKD: chronic kidney disease; HF: heart failure.

Considering the risk of cardiovascular events and the annual cost, the costs of informal care related to cardiovascular events per patient with CKD would be €1,368.34 and €1,706.27 with and without RAAS inhibitors, respectively. The costs are €2054.73 and €2,559.40 in HF. As for the costs of informal care related to the progression of CKD, they amount to €82.00 and €133.24.

Indirect costsIndirect costs included patients’ lost work productivity. These were estimated only in patients with CKD since the mean age of patients with HF (68.8 years) exceeds the Spanish retirement age.30 For this purpose, we estimated that 33.3% of patients with CKD who progress to hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis work.40 Patients on hemodialysis lose an average of 782.1 h of work per year,41 while a patient on peritoneal dialysis loses 14.9 h/year.42 Considering the average salary of the patients (€26,515.50 in persons aged 45–54 years and 27,252.17 € in those over 54 years31 and the average number of working hours per week (30.4 h),31 we estimate costs due to annual labor productivity losses of €4,477.78 and €83 in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, respectively. According to the distribution of patients with CKD (Table 4), the weighted average cost of work productivity losses due to disease progression amounts to €2,138.56.

Intangible costsIntangible costs were those related to premature mortality in patients with HF. This value was approximated according to the cost-utility threshold (cost per quality-adjusted life year gained) recommended in Spain (€25,000).43 Thus, the intangible cost per premature mortality in patients with HF who continue treatment with RAAS inhibitors amounts to €4,250 compared to €7,246 in patients who discontinue this treatment.

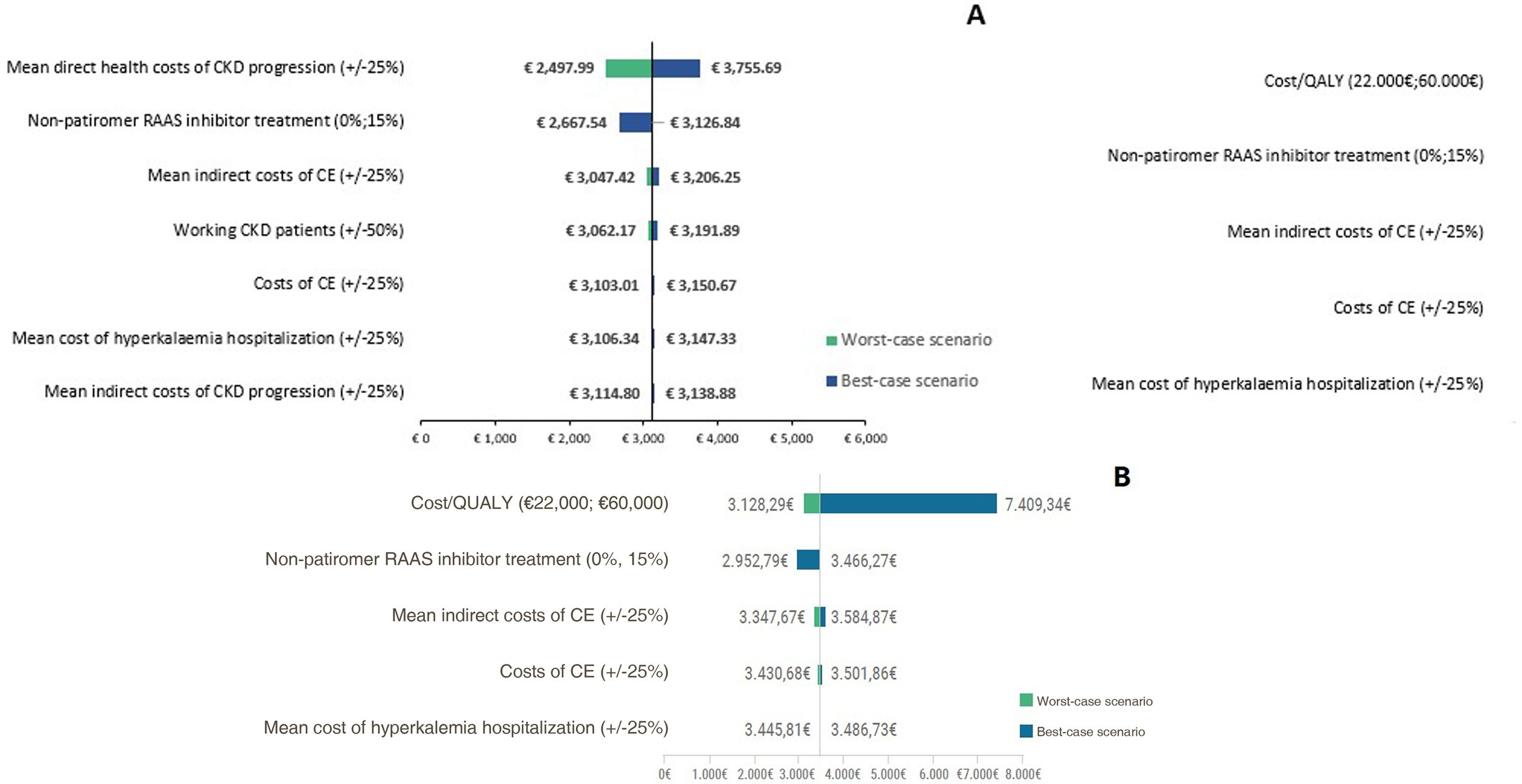

Sensitivity analysisA deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed to validate the consistency of the study results, varying the following parameters: costs of cardiovascular events (±25%); mean direct health care cost of CKD progression (±25%); mean cost of informal care (±25%); mean cost of hospitalization for hyperkalemia (±25%); cost/quality-adjusted life-year (quality-adjusted life-year) (€22,000; €60,000); percentage of patients with CKD who are working (±50%); percentage of patients without patiromer who would maintain treatment with RAAS inhibitors (0%; 15%).

ResultsOutcomes in patients with chronic kidney diseaseThe average cost of a patient with CKD and hyperkalemia without patiromer treatment is €9,834.09. The use of patiromer could reduce this cost to €6,707.25, generating a saving of 31.8% (Fig. 2). Direct health care costs represent more than 70% of the cost. The average annual cost of treatment with RAAS inhibitors in patients with patiromere is estimated at €61.42. Considering the risk of cardiovascular events and progression of CKD, as well as the risk reduction due to treatment with RAAS inhibitors, the direct non-health care costs without patiromer amount to €1,839.51 and with patiromer to €1,473.69, which represents a saving of 19.9% with patiromer. Indirect costs, labor productivity losses, are also 36.2% lower with the use of patiromer.

Outcomes in patients with heart failureThe average cost of a patient with HF and hyperkalemia without treatment with patiromer amounts to €10,739.37. The use of patiromer could reduce the cost to €7273.10, generating a saving of 32.3% (Fig. 2). The intangible cost of premature death accounts for more than 60% of the cost in patients with HF. The use of patiromer would reduce this cost by 38.87%. Direct non-health care costs also represent an important weight in the treatment of these patients. Considering the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events due to treatment with patiromer and, therefore, the maintenance of the RAAS inhibitors, there would also be a saving of 18.54% in informal care. Finally, in terms of direct health care costs, the use of patiromer would generate savings of 18.54% in costs related to cardiovascular events and 49.40% in those due to hospitalizations for hyperkalemia. The average annual cost of treatment with RAAS inhibitors in patients also taking patiromer is estimated at €48.78.

Sensitivity analysisThe results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Fig. 3. In CKD, the parameters that have the greatest impact on the result are the variation in the direct health care cost of CKD progression (±20.11%) and the percentage of patients without patiromer who maintain treatment with RAAS inhibitors (0%; −14.69%). 100% of the sensitivity analyses show that the use of patiromer in patients with CKD would generate savings for society, which demonstrates the consistency of the results. In HF, the parameters that have the greatest impact on the result are the variation in the cost per quality-adjusted life year (−9.75%; 113.76%) and in the percentage of patients without patiromer who maintain treatment with RAAS inhibitors (0%; −14.81%). As in CKD, 100% of the sensitivity analyses show that the use of patiromer in patients with HF would generate savings for society, which demonstrates the consistency of the results.

DiscussionThe present study analyzed the annual economic impact, per patient, of the use of patiromer in patients with hyperkalemia and CKD or HF in Spain, estimating annual savings of €3,127 (31.8%) and €3,466 (32.3%) in CKD and HF, respectively, which would offset the pharmacological cost of patiromer. In CKD, the greatest savings come from delaying disease progression (80.4%) and reducing the need for informal care (11.7%), while in HF the savings come from reducing mortality (81.4%) and informal care (13.7%).

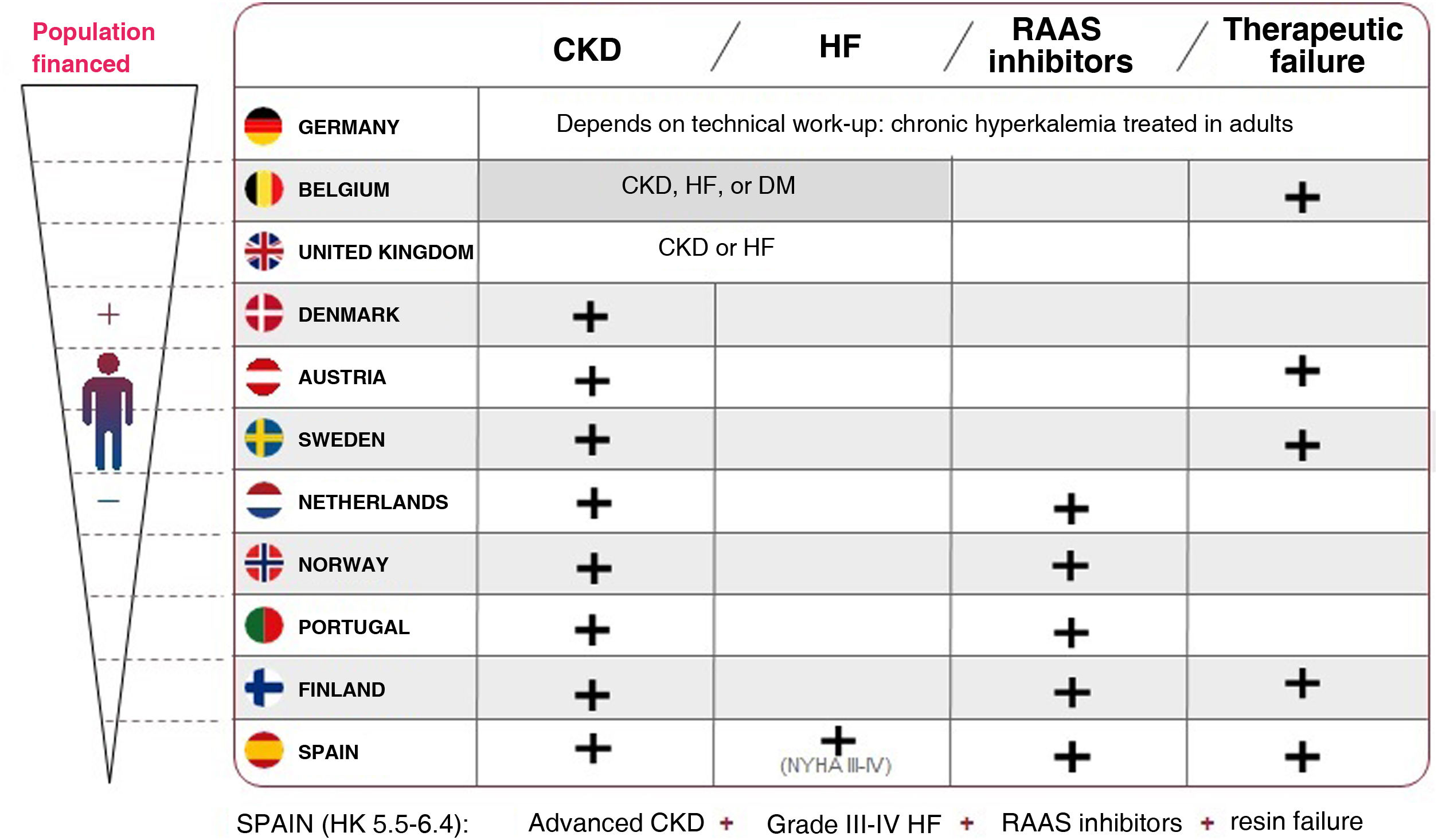

Although the indication for the new potassium binders is for the treatment of hyperkalemia in adults, and their use is recommended by the main scientific societies, currently in Spain the reimbursement of these drugs is restricted to patients with double comorbidity (CKD and HF at the same time),3 specifically for “patients with advanced CKD and grade III-IV HF and with mild to moderate hyperkalemia (5.5–6.4 mmol/l), in treatment with RAAS inhibitors and in whom its continuation is considered essential, and with failure or intolerance to ion exchange resins.”

The results of the present study support the savings that the use of patiromer signify in the population with CKD alone and also in the population with HF alone, and this finding may contribute in the future to expanding the available evidence to redefine the use of these products, which is currently restricted in Spain to patients with specific permission for prescription, unlike in other EU countries (Fig. 4).

Chronic hyperkalemia generates a high consumption of healthcare resources, primarily due to hospitalizations, with an average stay that varies according to severity: between 1.5 days in mild forms to 14 days in severe forms.33 In Spain, in 2019, there were 728 and 27,996 primary and secondary diagnoses respectively in patients hospitalized for hyperkalemia; and there were 2225 hospitalizations due to hyperkalemia as the main diagnosis. This represents a total direct health care cost of almost 8 million euros.36 In adition, this pathology is associated with higher rates of hospitalization, and visits to emergency department, and hospital clinics (up to 14, 10 and 52% respectively).26 In addition, the existence of a first hyperkalemia event favors the occurrence of other episodes, with an increasingly shorter period between the subsequent episodes.44,45 All this indicates that the management of hyperkalemia generates a high consumption of health care resources, both in patients with CKD and HF, which has an economic impact on the Spanish NHS, increasing direct health care costs, as well as on society due to productivity loss, informal care, and premature death.

The use of patiromer achieves sustained potassium reduction from the first dose and long-term control of hyperkalemia and allows treatment with RAAS inhibitors. It is administered once daily, which facilitates therapeutic compliance, and does not contain sodium, making it suitable for administration in patients with CKD or HF.14,46 This study shows that this economic impact could be reduced, thanks to better control of hyperkalemia with patiromer, generating savings for the NHS and society.

To our knowledge, to date, there have been no studies estimating the impact and possible savings of better control of hyperkalemia in patients with CKD and HF. Only studies quantifying the use of resources in these patients have been performed. In Germany, a study of more than 3000 patients showed a significantly higher number of hospitalizations in patients with hyperkalemia than in those without hyperkalemia.47 In patients with CKD in the United States, the risk of hospitalization in patients with hyperkalemia was almost twice as high as in patients without hyperkalemia (75.8% vs. 42.3%), and in patients without hyperkalemia the risk of hospitalization decreased after each admission (22.8% after the first admission and 4.2% after the fourth and subsequent admissions), while in patients with hyperkalemia this risk remained relatively constant (26.4% and 17.8%, respectively).5

However, our study has limitations. First, the costs may vary considering the prices specific to each hospital, although, given that these costs are not all public, we used the publicy available prices paid by the autonomous communities. However, the sensitivity analyses performed on the costs show that the variability of these costs would not have an impact on the results. Second, the percentage reduction in hospitalizations due to the administration of patiromer comes from the clinical trial; however, given that the reduction in hospitalizations in real clinical practice is unknown, a new cost analysis is recommended once the evidence is available.

ConclusionsThe incorporation of patiromer makes it possible to control hyperkalemia and, consequently, to maintain treatment with RAAS inhibitors in patients with CKD or HF, generating annual savings in Spain of 32% (€3,127 in CKD; €3,466 in HF). This strategy could reduce the health care burden of these pathologies and support the sustainability objectives of the Spanish NHS by containing the cost associated with the management of chronic hyperkalemia in Spain. The results of the study support the savings represented by patiromer and may help to expand the available evidence in the future to redefine the use of these products for all patients with hyperkalemia.

FinancingFunded by CSL Vifor.

Conflict of interestP.S. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentation from CSL Vifor, Amgen, Fresenius, Astra Zeneca, Alexion, Braun, and Baxter; support for meeting attendance from Nipro, CSL Vifor, Amgen, Fresenius, Astra Zeneca and Baxter, and Advisory Board participation from Astellas, CSL Vifor, Baxter, Astra Zeneca. R.B. has received honoraria from CSL Vifor and Astra Zeneca. Y.I.M., A.I. and A.G.D. work at Weber, a consulting firm that has received funding from CSL Vifor. M.V. and V.C. work at CSL Vifor.