The coexistence of aortic stenosis (AS) and iron-deficiency anaemia due to gastrointestinal bleeding caused by angiodysplasia is known as Heyde syndrome. It was described in 1958 by Dr. Edward Heyde.1 It is now defined by the triad of severe AS, coagulopathy due to acquired type 2A von Willebrand syndrome and anaemia secondary to angiodysplasia-induced gastrointestinal bleeding.2–4 We present the case of a 63-year-old woman with chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to reflux nephropathy, on haemodialysis since 1989, with a history of two kidney transplants, both grafts were lost due to acute rejection, severe mitral insufficiency with mitral valve replacement by mechanical prosthesis in 2002, requiring anticoagulant therapy with acenocoumarol, and with severe AS.

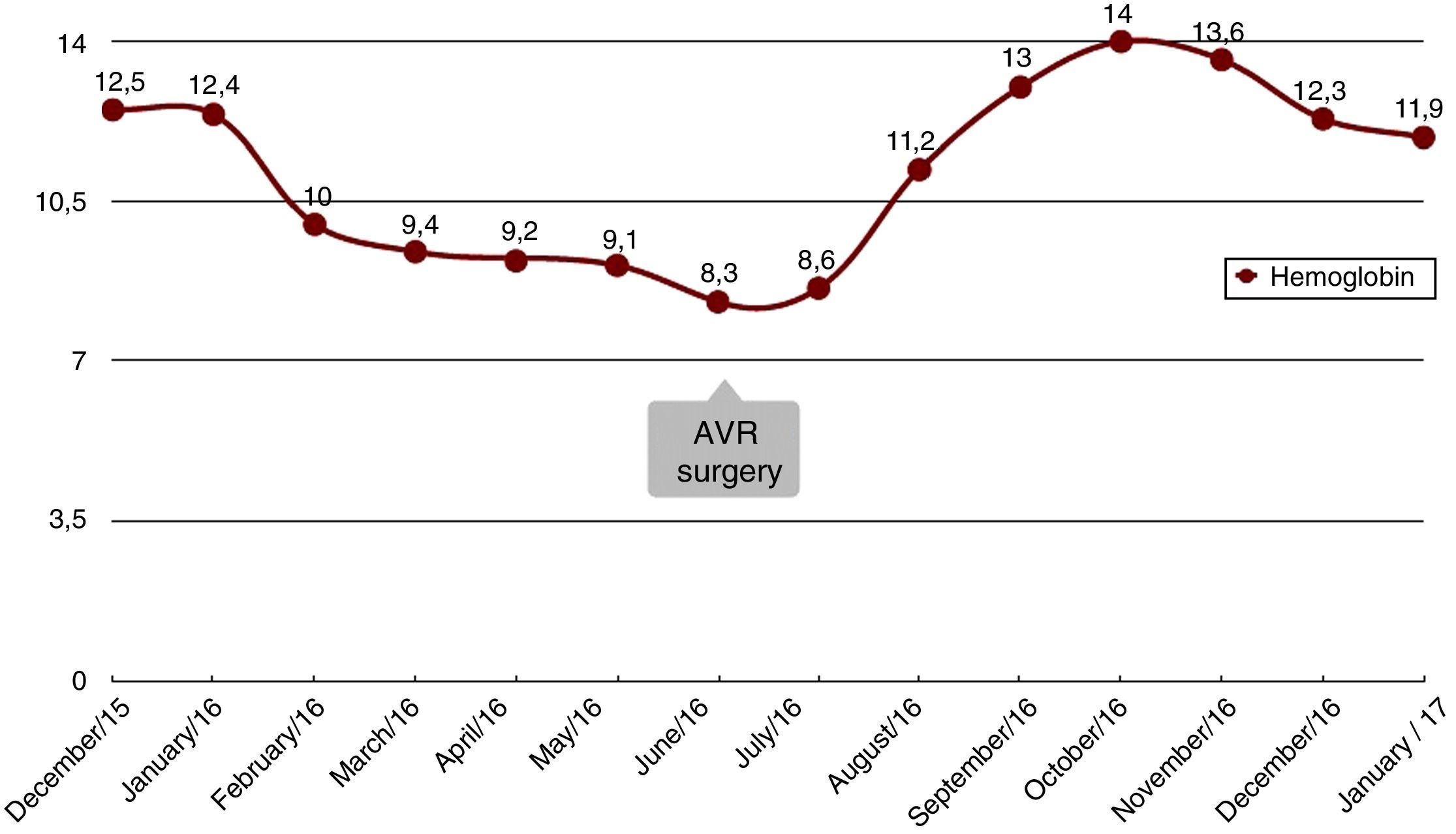

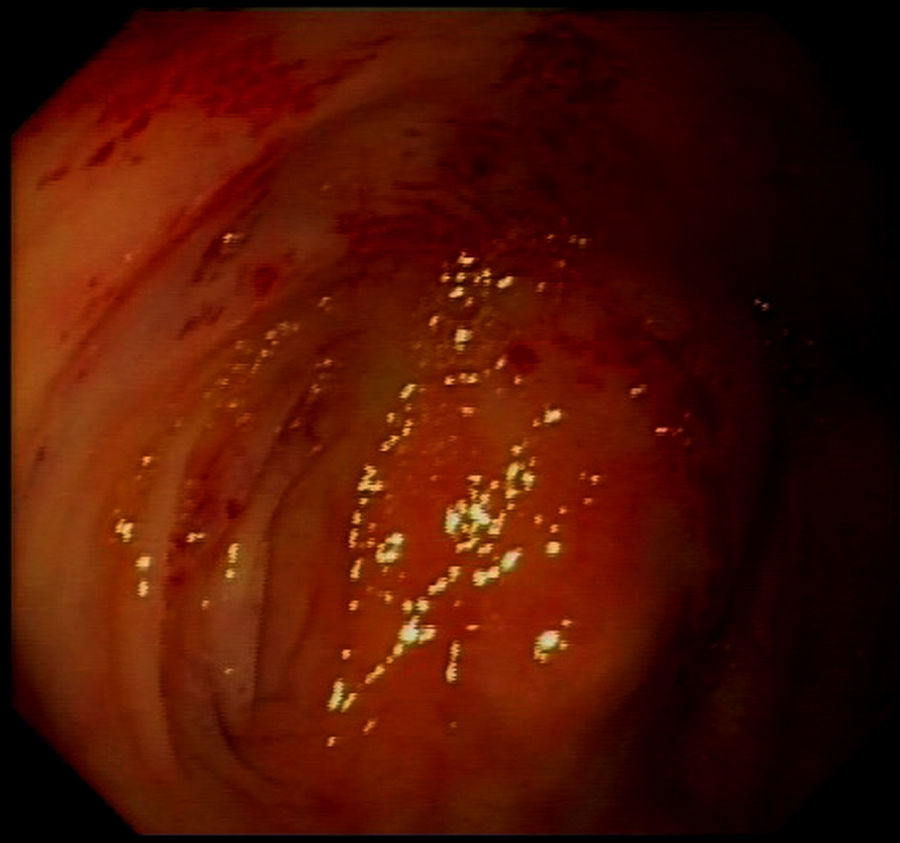

The patient presented with rectorrhagia and haematochezia in January 2016, with anaemia and a decrease in haemoglobin from 12.5 to 9g/dl; the platelets were normal, the INR was within a suitable range and the transferrin saturation fell to 18%. She did not receive heparin during dialysis. Despite the increased provision of IV iron and the increased dose of erythropoietin from 12,000 to 24,000IU weekly, she needed a mean of two packed red blood cell units per week to maintain haemoglobin levels around 10g/dl (Fig. 1). The colonoscopy (Fig. 2) revealed erythematous lesions measuring 2–3mm, which looked like small haematomas, without having the appearance of angiodysplasias, and there was no lesion which could be acted on. During the following weeks the bleeding was more intense thus additional transfusions were required each week. Another proctosigmoidoscopy was performed, which only showed fragility in the mucosa of the descending colon.

Coinciding with the anaemia, the patient presented with a worsening of her functional heart classification. The echocardiogram showed decreased LVEF, from 55% to 44%, and progression of the AS (valve area of 0.4cm2). The coronary angiogram showed no significant lesions. In June 2016, aortic valve replacement (AVR) was performed with an mechanical prosthesis ATS no. 21. The patient showed a complete resolution of symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding in the first week after the AVR, indicating that the most probable cause was Heyde syndrome.

In the months after the AVR, the patient was asymptomatic, with no episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, haemoglobin remained stable at 12g/dl without the need for transfusions, IV iron has been suspended and the dose of erythropoietin has been reduced to 8000IU per week. The patient was maintained on anticoagulation therapy with acenocoumarol in a suitable range.

Angiodysplasias are small, dilated, tortuous vessels with a diameter smaller than 1cm. A 30–40% of gastrointestinal haemorrhages of unknown cause are related to angiodysplasias. They primarily cause gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly and in patients with CKD. They can be detected earlier in patients with CKD, and are the principal cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (19–32%).5

The most common valve lesion in the elderly is AS. The prevalence of critical AS is 1–2% at 75 years and 6% at 85 years.3,4 AS causes low-grade chronic hypoxia, which stimulates the formation of angiodysplasias.3,5 Pate et al.6 and Shoenfeld et al.7 found a significant correlation between AS and gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to angiodysplasias.

The mechanism involved in AS which causes acquired type 2A von Willebrand syndrome is the mechanical disruption of the large vWF multimers due to the high tension caused by the turbulent flow when passing through the tight valve. Exposure to this tension causes a change in shape (from a spiral structure to an elongated filament) so it is exposed to protease ADAMTS13 activity and triggers proteolysis, which reduces the number of high molecular weight (HMW) vWF multimers. HMW vWF multimers are important for haemostasis; they mediate platelet aggregation and adhesion to the subendothelium of the damaged blood vessels and in situations of high-speed blood flow. The angiodysplastic vessels themselves are associated with high-speed blood flow. In the absence of these multimers, prolonged bleeding would be expected.2–4,8

Endoscopic treatments, embolisation, surgery, hormone therapy or octreotide only elicit short-term success.8 Stenotic valve replacement is the most effective treatment, as it corrects the blood supply to the intestine and the decreased HMW vWF multimers.2–4,8 A review of the Mayo Clinic9 presented 57 cases of Heyde syndrome treated with AVR, with a follow-up of 15 years. 79% of patients had no recurrence of bleeding, with a bioprosthesis as the valve of choice. King et al.10 observed a decrease in gastrointestinal bleeding after AVR in 93% of patients.

In patients with AS who develop anaemia due to gastrointestinal bleeding, as well as assessing the most common causes (ulcers, neoplasms, ischaemic colitis, etc.), the possibility of HS should be considered. In patients presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown cause, AS must be ruled out. The most effective treatment for complete resolution of the symptoms is AVR.

Please cite this article as: Milla M, Hernández E, Mérida E, Yuste C, Rodríguez P, Praga M. Síndrome de Heyde: resolución de anemia tras reemplazo valvular aórtico en paciente en hemodiálisis. Nefrología. 2018;38:327–329.