The relationship between parasites and glomerulonephritis (GN) is well documented in certain parasitoses, but not in cases of Strongyloides stercolaris (S. stercolaris) where there are few cases described being the majority GN of minimal changes. We report a case of hyperinfestation by S. stercolaris in a patient affected by a membranous GN treated with oral corticosteroids with fatal outcome for the patient. This case provides a double teaching: first about a rare association of strongyloid and membranous GN and second about the importance of establishing a diagnosis of suspected and appropriate treatment for certain infections or diseases with little clinical expression before starting any immunosuppressive treatment.

La relación entre parásitos y glomerulonefritis (GN) está bien documentada en determinadas parasitosis, no así en casos de Strongyloides stercolaris (S. stercolaris), donde hay pocos casos descritos, siendo la mayoría GN de cambios mínimos. Reportamos un caso de hiperinfestación por S. stercolaris en un paciente afectado de una GN membranosa tratado con corticoides por vía oral con resultado fatal para el paciente. Este caso nos aporta una doble enseñanza: en primer lugar, acerca de una asociación rara de estrongiloidiasis y GN membranosa, y en segundo lugar, sobre la importancia de establecer un diagnóstico de sospecha y tratamiento adecuados ante determinadas infecciones o enfermedades con poca expresividad clínica antes de iniciar cualquier tratamiento inmunosupresor.

The relationship between parasitic infections and glomerulonephritis (GN) is well documented in malaria, schistosomiasis, trypanosomiasis, toxoplasmosis, visceral leishmaniasis, echinococcosis and filariasis. However, it is not well-documented in cases of Strongyloides stercoralis (S. stercoralis), where there are few cases reported, with the majority being minimal change GN (MCGN). Furthermore, in these situations, the immunosuppression used for the treatment of kidney disease may trigger a Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome with a fatal outcome for the patient; hence the importance of establishing a suspected diagnosis and appropriate treatment in those patients who are considered at-risk. We report a case of S. stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome in a patient affected by membranous GN treated with oral corticosteroids.

Case reportThe case discusses a 52-year-old male patient from Ecuador who had been living in Spain for more than one year, with a previous history of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, undergoing treatment with lisinopril and atorvastatin. He was referred to the emergency department after follow-up tests at his health centre showed kidney failure with plasma creatinine (pCr) of 4.3mg/dl and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by CKD-EPI of 13ml/min/1.73m2. Six months previously, he had pCr of 1.36mg/dl and urinalysis with proteinuria and microscopic haematuria. The complementary tests revealed a glomerular proteinuria of 10g per day with microscopic haematuria. The serological tests (hepatitis B and C virus, HIV, CMV, Epstein–Barr virus) and autoimmunity tests (antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies, proteinogram, complement, extractable nuclear antigens) were negative/normal. The A2 antiphospholipid antibodies were not available at the time. He presented occasional fluctuating mild eosinophilia (1–12%, with eosinophils 100–900/mm3).

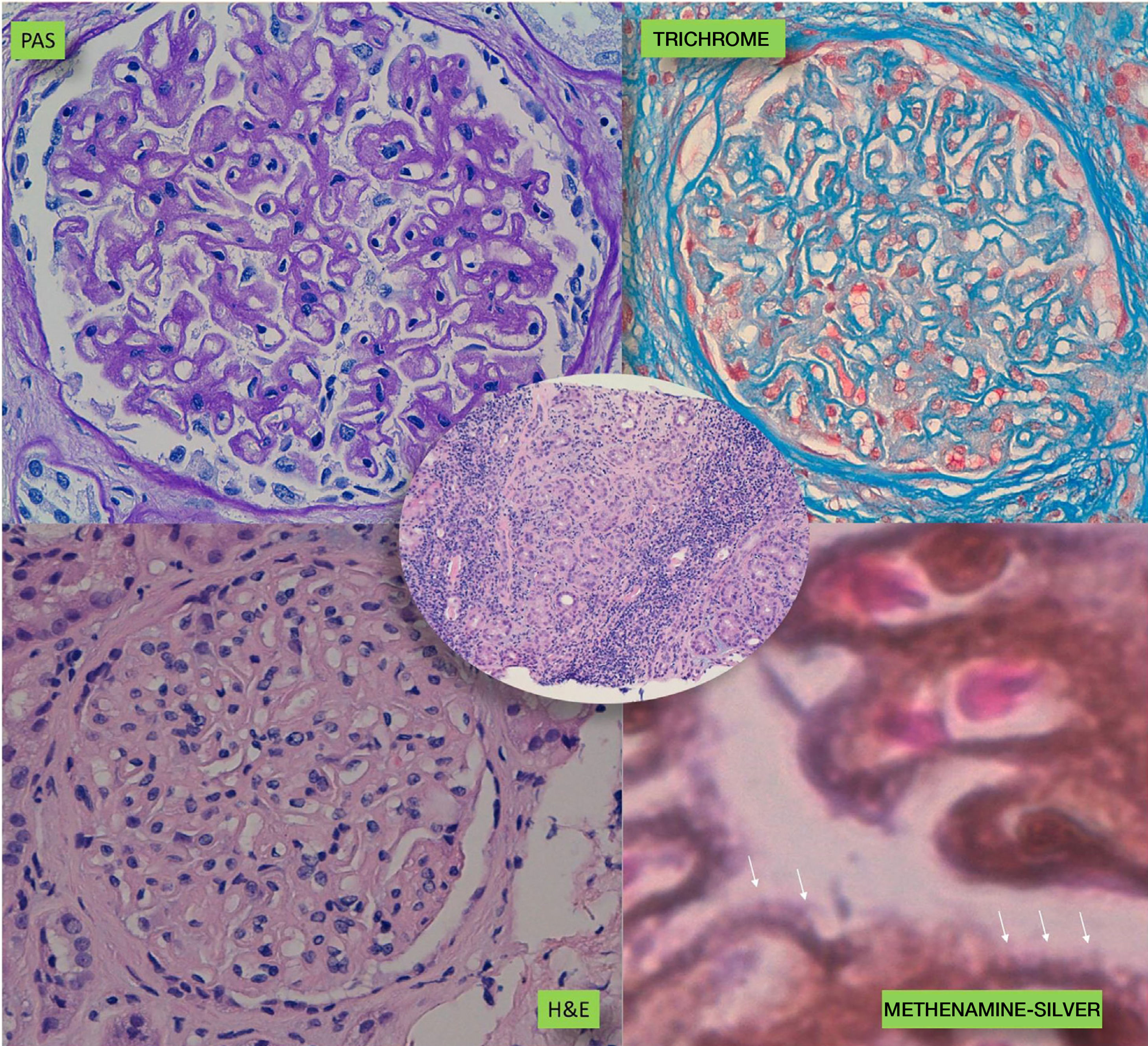

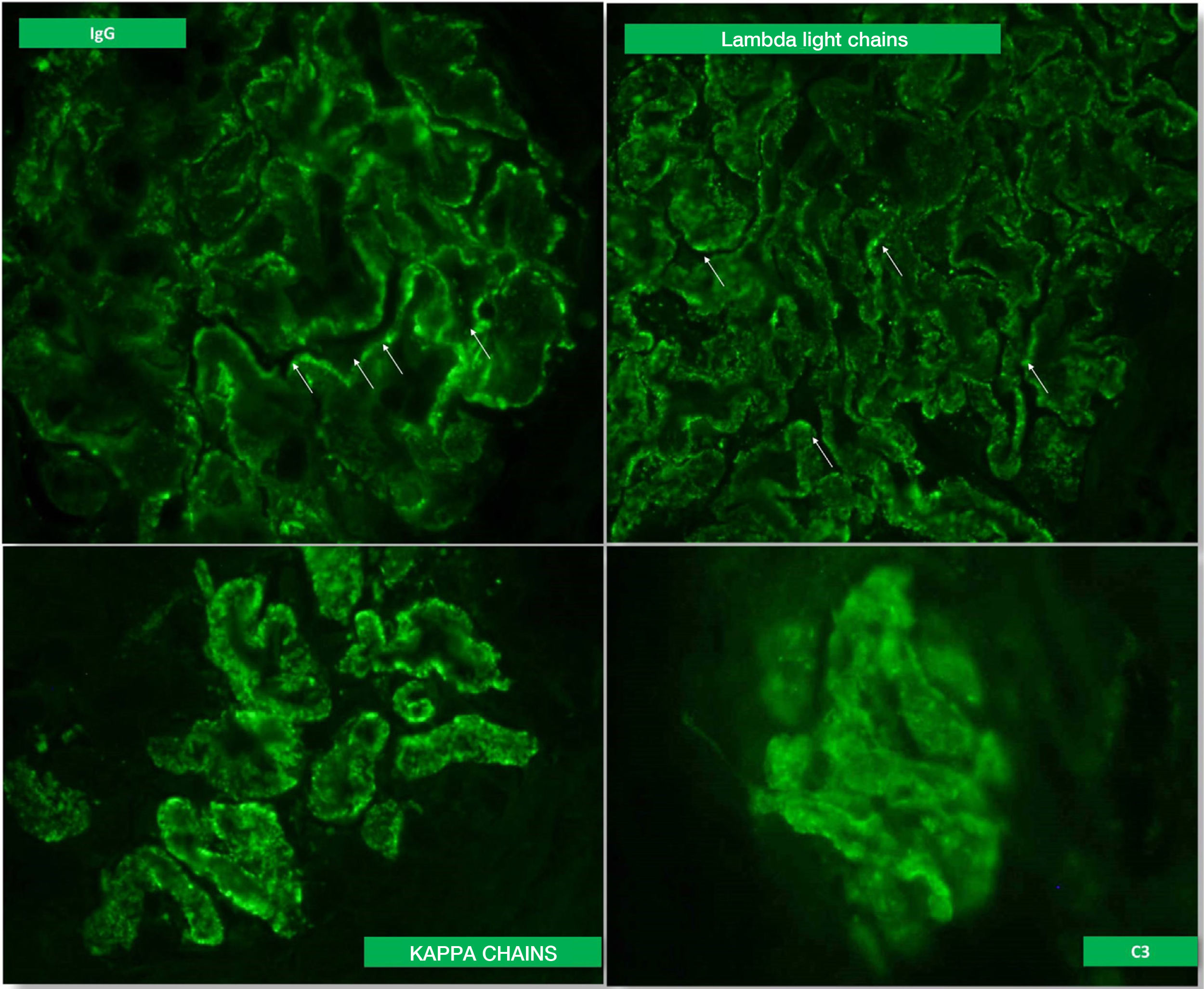

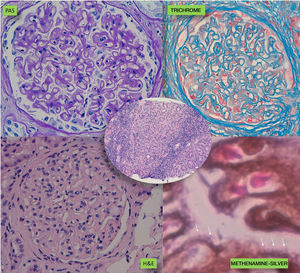

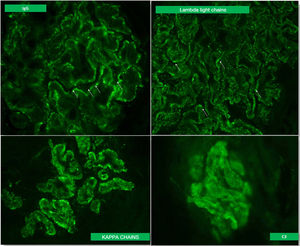

A kidney biopsy was performed with a diagnosis of membranous GN in stage 2–3, with marked interstitial inflammation (Fig. 1). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for granular deposits in the basement membrane for IGG, kappa and lambda chains, and in a lower proportion for C3, with these being negative for the rest of the immunoglobulins and C1q (Fig. 2). In view of these findings with significant interstitial inflammation and given the patient's kidney failure, it was decided to start treatment with prednisone at doses of 60mg/day. In addition, the following were added to the treatment: amlodipine, darbepoetin, furosemide, bicarbonate, atorvastatin, iron, omeprazole, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, calcium and vitamin D.

After one month, he came to the clinic reporting anorexia and nonspecific dyspepsia. Kidney function had improved to pCr of 2.3mg/dl and eGFR 30ml/min./1.73m2, as had proteinuria, to 2g/day. Of note from the blood tests were moderate hyponatraemia (127mEq/l) with hyperkalaemia (6.7mEq/l), elevation of CA 125 and corticotropin with cortisol in plasma normal. It was decided to admit the patient to hospital to complete testing and on the fourth day he started to have a low-grade fever, tachycardia, bradypsychia and hyporesponsiveness. A few hours later, he developed a generalised epileptic seizure with meningeal signs. A cranial computed tomography scan was performed which ruled out space-occupying lesions and acute haemorrhage; empirical therapy was initiated with ceftazidime and ampicillin, and a lumbar puncture was performed which showed data compatible with bacterial meningitis. The CSF culture identified Escherichia coli. The cephalosporin was therefore replaced with a carbapenem. The clinical course was poor and after 48h he developed dyspnoea, with severe overall respiratory failure and fluctuations in level of consciousness. He therefore required transfer to the ICU with the diagnosis of septic shock secondary to meningitis for assisted mechanical ventilation and support with inotropic amines.

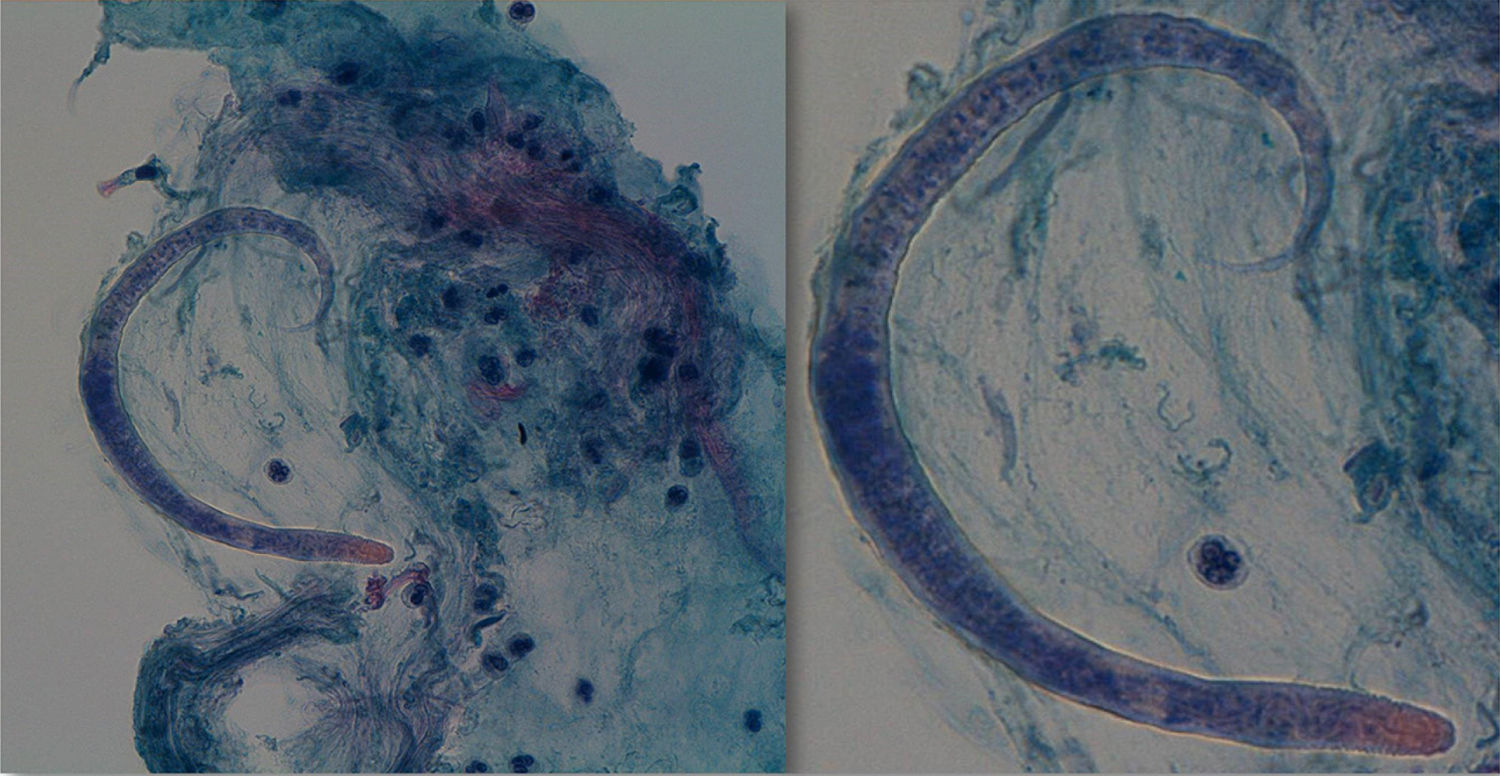

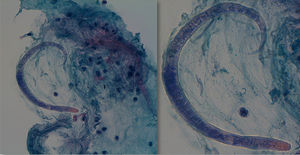

During his stay in the ICU, he developed bicytopenia which required a blood transfusion; adult respiratory distress syndrome secondary to pneumonia due to Cryptococcus neoformans; new culture of CSF with growth of Enterococcus faecium; oligoanuric renal failure which required CVVH; severe malnutrition and polyneuropathy of the critically ill patient. In the anatomopathological study of the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, an inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils and the presence of parasites indicative of S. stercoralis was observed (Fig. 3), which were also subsequently identified in the stool culture. He received treatment with meropenem, vancomycin, liposomal amphotericin B and subsequently with fluconazole, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ivermectin and albendazole. While he was being monitored, CMV in blood developed (1000copies/ml), so ganciclovir was added. Despite the stool culture, BAL culture and blood cultures becoming negative, the patient did not improve clinically and remained in a state of coma vigil. The electroencephalogram revealed a severe slowing down and diffuse suppression of brain activity, and the brain magnetic resonance imaging identified signs of hyperintensity on a T2 sequence in the right frontal parasagittal region and the occipital horn of the right lateral ventricle, indicative of the persistence of the inflammatory/infectious process. Despite maintaining an appropriate antibiotic therapy for the cultures, the patient died after developing respiratory failure due to nosocomial pneumonia caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

DiscussionThis case report reveals the devastating prognosis of S. stercoralis hyperinfection in a patient immunosuppressed due to corticosteroids and who, a priori, did not seem to have other risk factors. S. stercoralis is a soil-transmitted helminth which measures 2.5mm in a female adult state and 0.3–0.6mm in the larval stage, which lives mainly in Eastern Europe, South-east Asia, South America and sub-Saharan Africa, with prevalence rates close to 30%.1 Spain was an endemic country, in particular in the Mediterranean area, although in recent decades the number of imported cases have increased as a result of immigration.2 It is transmitted by contact with the soil or by the intake of contaminated food or water. It lives in the upper jejunal mucosa and is reproduced by parthenogenesis, completing its life cycle by transforming from non-infective rhabditiform larvae into infective filariform larvae which self-infect the host crossing the intestinal lumen, reaching the lymph nodes of the wall, and from there the bloodstream, from where it reaches the liver, and subsequently the lungs, kidneys and central nervous system, self-perpetuating its infection.

When an intestinal or pulmonary invasion of a large number of larvae occurs, it may trigger multiple organ failure which is known as hyperinfection syndrome. It is more common in elderly patients, patients with kidney disease, diabetes, malnutrition, in situations of achlorhydria and patients immunosuppressed due to any cause (leprosy, corticosteroid therapy, HIV, HTLV-I, anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy), post solid organ transplant or bone marrow transplant patients3–12 and, although rare, it can also occur in immunocompetent patients.

The diagnosis of S. stercoralis parasitic infection can be performed by detecting the parasites in faeces or in other biological samples in the case of hyperinfection. Direct viewing of faeces is used routinely in laboratories, but it has a very low sensitivity, with this sensitivity improving somewhat if repeated samples are used. A stool culture in agar and direct or indirect immunoassay methods can also be resorted to, detecting antibodies to Strongyloides.9

Ivermectin is considered the treatment of choice when there are symptoms of hyperinfection. Tiabendazole and albendazole achieve comparable remission results in uncomplicated infections, with these being more poorly tolerated than ivermectin.9 In Spain, ivermectin should be requested as a foreign drug and the recommended conventional dose is 0.2μg/kg/day for two days, with it being necessary to repeat the dose after 15 days.9 In cases of cumulative dose of prednisone above 420mg in four weeks, some authors recommend prophylaxis in patients at risk of infestation.13

In the ten cases reported in the literature of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome,14 88.9% were males, with a mean age of 48 (24–79), with onset of abdominal pain as the most common symptom (88.9%) and, in a lower percentage, fever (66.7%), pulmonary infiltrates (66.7%), diarrhoea (44.4%), eosinophilia (66.7%) and mortality of 22.2%. In overall data, eosinophilia does not exceed 20–35% and tends to be episodic and non-continuous. There are doubts regarding its prognostic value, as it seems to represent an adequate Th2-type immune response, but the data are contradictory. The suspected diagnosis is fundamental in immunosuppressed patients, especially those on treatment with corticosteroids, with eosinopenia or eosinophilia, with protein-losing enteropathy or malabsorption syndrome, nausea, vomiting and ileus, and in patients from endemic countries. Chan et al.14 report the case of a 72-year-old Vietnamese male, resident in Australia, affected by diabetes mellitus and asthma, who developed hyperinfection syndrome after recent laparoscopic surgery and died on the seventh day after starting treatment with ivermectin. Clinically, it has been associated with signs of pseudo-obstruction and may become complicated with tumour processes, such as colon adenocarcinoma, GIT T-cell lymphoma and MALT lymphoma of the stomach and colon,15 in relation to co-infection with Helicobacter pylori, and resolution when treating both infections. The mechanism assumes the interaction of a parasite antigen with the colon mucosa causing a continuous stimulus of T-lymphocytes.

In an extensive review of cases of strongyloidiasis reported in Spain from 2000 to 2015,2 18 cases were gathered; 66.7% were males with a mean age of 40 (21–70). A total of 94.4% were of foreign origin, mainly from South America (82.3%) and secondly from West Africa (17.6%). Only one indigenous case has been reported since 2006. Some 77% of them were immunosuppressed due to corticosteroid therapy, HIV, HTLV and solid organ transplant. The initial symptoms were gastrointestinal in 55.6% of cases, accompanied by a fever in 27.8%. One case had nephrotic syndrome, with no more data, which is why it was not included in the total count. Mortality was 11.1%.

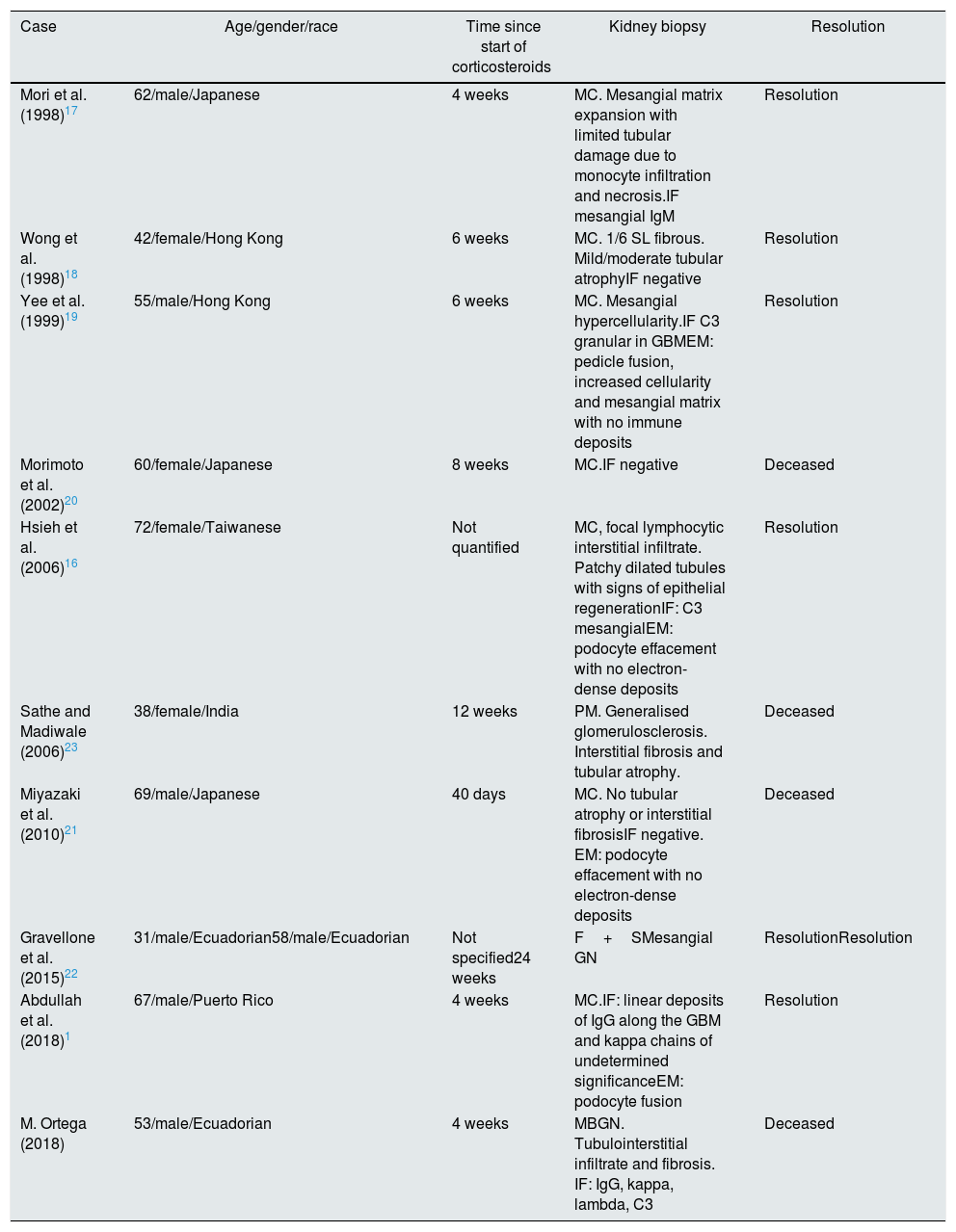

There are 18 reported cases which associate Strongyloides infection with glomerular disease, 11 of which have histological diagnosis (Table 1).10,16–23 Almost all started between four and eight weeks after starting corticosteroid therapy and most of them are defined as MCGN. In general, the diagnosis of GN preceded that of parasitic infection, which was revealed after the corticosteroid therapy, except in the case reported by Hsieh et al.,16 which started with the parasitic infection while the GN developed three months later and was resolved after initiating treatment with ivermectin. Four of the patients died. In the other patients the parasitic infection and the kidney disease was resolved, except in one of the cases reported by Gravellone et al.,22 an Ecuadorian affected by focal segmental GN treated with prednisone, in whom the renal impairment persisted after resolution of the Strongyloides infection.

Summary of cases of Strongyloides infection with nephrotic syndrome published in the literature.

| Case | Age/gender/race | Time since start of corticosteroids | Kidney biopsy | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mori et al. (1998)17 | 62/male/Japanese | 4 weeks | MC. Mesangial matrix expansion with limited tubular damage due to monocyte infiltration and necrosis.IF mesangial IgM | Resolution |

| Wong et al. (1998)18 | 42/female/Hong Kong | 6 weeks | MC. 1/6 SL fibrous. Mild/moderate tubular atrophyIF negative | Resolution |

| Yee et al. (1999)19 | 55/male/Hong Kong | 6 weeks | MC. Mesangial hypercellularity.IF C3 granular in GBMEM: pedicle fusion, increased cellularity and mesangial matrix with no immune deposits | Resolution |

| Morimoto et al. (2002)20 | 60/female/Japanese | 8 weeks | MC.IF negative | Deceased |

| Hsieh et al. (2006)16 | 72/female/Taiwanese | Not quantified | MC, focal lymphocytic interstitial infiltrate. Patchy dilated tubules with signs of epithelial regenerationIF: C3 mesangialEM: podocyte effacement with no electron-dense deposits | Resolution |

| Sathe and Madiwale (2006)23 | 38/female/India | 12 weeks | PM. Generalised glomerulosclerosis. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. | Deceased |

| Miyazaki et al. (2010)21 | 69/male/Japanese | 40 days | MC. No tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosisIF negative. EM: podocyte effacement with no electron-dense deposits | Deceased |

| Gravellone et al. (2015)22 | 31/male/Ecuadorian58/male/Ecuadorian | Not specified24 weeks | F+SMesangial GN | ResolutionResolution |

| Abdullah et al. (2018)1 | 67/male/Puerto Rico | 4 weeks | MC.IF: linear deposits of IgG along the GBM and kappa chains of undetermined significanceEM: podocyte fusion | Resolution |

| M. Ortega (2018) | 53/male/Ecuadorian | 4 weeks | MBGN. Tubulointerstitial infiltrate and fibrosis. IF: IgG, kappa, lambda, C3 | Deceased |

The case described illustrates the high mortality and severity of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome triggered by the immunosuppression which is necessary and used routinely in the treatment of glomerular diseases. This case teaches us two things. First, about a rare association of strongyloidiasis and membranous GN, and second, and most importantly, about the significance of establishing a suspected diagnosis and appropriate treatment in the face of certain infections or diseases with little clinical expression in at-risk patients before starting any immunosuppressive therapy. It is necessary to pay special attention to the individual risk of each patient of infectious complications, referring to the medical history and investigating their origin, behaviours and travel to risk areas. In the case of S. stercoralis, a mild and fluctuating eosinophilia in patients from endemic areas may be the only abnormality that helps us to establish a suspected diagnosis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ortega-Díaz M, Puerta Carretero M, Martín Navarro JA, Aramendi Sánchez T, Alcázar Arroyo R, Corchete Prats E, et al. Inmunosupresión como desencadenante de un síndrome de hiperinfestación por Strongyloides stercolaris en la nefropatía membranosa. Nefrologia. 2020;40:345–350.