Patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) are key tools for advancing patient-centered clinical practice, with proven benefits for health outcomes. Their application has been extended to different chronic diseases, but there are few studies involving patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), a population that is aging and frail. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between frailty and self-reported health-related quality of life in patients with advanced CKD who are eligible for kidney transplantation (KT).

Materials and methodsKT candidates who were evaluated in the outpatient clinic were included in the study. The PROMIS-29® and PROMIS-Global Health® questionnaires were administered, and T-scores were calculated for each domain. Frailty was assessed using the Fried scale, categorizing participants as frail/pre-frail if FRIED > 0. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were also collected.

Results139 KT candidates were included in the study: 32% were women, the mean age was 63.5 years, 43.9% were on dialysis, and 64.5% were frail. 71.2% responded to the administered PROMIS. Overall, KT candidates reported their mental health as good (48 ± 7.4) and their physical health as fair (42.8 ± 7.3). T-scores for anxiety, fatigue, social functioning, sleep disturbance, pain, and depression were within the normal range compared to the general population. When comparing frail with robust patients, only the physical domain of PROMIS-Global Health® and physical function of PROMIS-29® were worse in the frail group. No differences were found in the other domains.

ConclusionsFrail kidney transplant candidates report worse physical function when assessed using PROMs tools. The systematic implementation of PROMs might help to implement strategies to optimize access to the waiting list, improve postKT outcomes, and enhance overall patient care.

Los resultados percibidos por el paciente (PROMs) son herramientas clave para avanzar hacia una práctica clínica centrada en el paciente, con beneficios demostrados para su estado de salud. Aunque su implementación se ha extendido en diversas enfermedades crónicas, existen pocas experiencias en personas candidatas a trasplante renal (TR), una población cada vez más envejecida y frágil. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la relación entre fragilidad y calidad de vida autoreportada relacionada con la salud en personas con enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA) candidatas TR.

Material y métodosSe incluyeron candidatos a TR evaluados en la consulta de acceso al TR. Se administraron los cuestionarios PROMIS-29® y PROMIS-Global Health® y se calculó el T-score para cada dominio. La fragilidad se evaluó mediante la escala de Fried, agrupando como frágiles/prefrágiles (FRIED > 0). También se recogieron variables sociodemográficas y clínicas.

ResultadosDe un total de 139 pacientes incluidos, el 32% eran mujeres y la edad media fue de 63,5 años, el 43,9% estaba en diálisis y el 64,5% tenían algún grado de fragilidad. El 71,2% contestaron los cuestionarios administrados. De forma global, los candidatos a TR tuvieron una percepción de su estado mental como buena (48 ± 7,4) y estado físico como regular (42,8 ± 7,3). Las puntuaciones de ansiedad, fatiga, habilidades sociales, alteración del sueño, dolor y depresión estaban dentro del rango normal comparado con la población general. Cuando comparamos a los pacientes frágiles con los robustos, solo el dominio físico de PROMIS-Global-Health® y la función física de PROMIS-29® fueron peores en el grupo de pacientes con algún grado de fragilidad. No se encontraron diferencias en el resto de los dominios.

ConclusionesLos candidatos a TR frágiles presentan una peor percepción de su función física medida con herramientas PROMs. La implementación sistemática de PROMs podría facilitar estrategias dirigidas a mejorar los resultados en salud, optimizando el seguimiento en lista de espera y el acceso al trasplante.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a major global public health problem.1 In Spain, the number of people receiving renal replacement therapy has increased by 20% in the past decade, with a prevalence of 1.406.4 people per million inhabitants reported, according to the latest report of the Spanish Registry of Dialysis and Transplantation (Registro Español de Díalisis y Trasplante, or REDYT).2 This sustained increase has rendered CKD as a health priority, which is due to both its high clinical burden and its economic and social impacts.3

In this context, renal transplantation (KT) represents the best therapeutic option for improving the survival and quality of life of patients with advanced CKD, even in older people with concurrent diseases.4 However, access to KT requires an exhaustive evaluation process to ensure that the procedure is safe and offers the maximum possible benefit. In recent years, the assessment of frailty has been proposed as a key factor in the evaluation process of KT candidates because it allows for the assessment of their degree of vulnerability beyond chronological age and the presence of comorbidities.5

Frailty (which is defined as the decrease in physiological reserves to cope with stressful situations) represents a particular challenge in the context of TR.6 In Spain, it is estimated that 70% of patients included on the waiting list (WL) for KT exhibit some degree of frailty.5 Several studies have demonstrated that this factor influences the results, both on the waiting list and after KT, as it is associated with a higher incidence of complications, an increase in hospitalization rates and lower patient survival.7,8 However, questions persist regarding how frailty affects other relevant aspects for patients, such as their quality of life or symptom control after KT.

Given this scenario, it is necessary to re-evaluate the models of care that place patients and their needs at the center of the care process. The incorporation of the results reported by patients (patient-reported outcome measures [PROMs]) has been proposed as a key strategy to evaluate fundamental aspects of health that transcend traditional clinical indicators.9 PROMs, which are defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as outcome measures communicated by the patient, are reports on the patient's health status that originate directly from the patient, without interpretations of their responses by clinicians or other individuals.10 These tools offer valuable information on the perceptions that patients themselves possess regarding their health status, functional capacity, quality of life and priorities in health care, which facilitates more personalized care aligned with their needs. Unlike classical clinical evaluations, these instruments directly collect the subjective perception of the patient, thus providing a perspective that is often unnoticed by health professionals.11 In fact, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines on the management of CKD emphasize that patients with CKD consider quality of life and symptom control as outcomes that are relevant or more relevant than survival itself.1

Despite the accumulating evidence of the value of PROMs in health care, there is little certainty regarding the application of these tools in individuals with CKD who are being evaluated as KT candidates.11 To date, the relationship between PROMs and frailty in this specific population has not been evaluated. An understanding of how frailty affects the perception that these patients have regarding their health, physical functionality, pain and emotional well-being could provide crucial information for optimizing clinical decision-making and transplant planning.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between frailty and health-related quality of life through the administration of PROMs in people with advanced chronic kidney disease who are candidates for KT.

Materials and methodsStudy designAn observational, descriptive and cross-sectional study was performed in a cohort of 139 KT candidates evaluated in the KT access consultation at the Hospital del Mar (Barcelona).

This study was performed following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5, as well as the protection of personal data and European Regulation 2016/679 on data protection. Similarly, this study was performed under the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization and Standards of Good Clinical Practice. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital del Mar within project 2024/11603.

Study populationAll patients with advanced CKD who were evaluated as KT candidates in the KT access consultation were invited to participate.

Study variablesThe following variables were collected from the clinical history: a) sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, nationality, level of education and cohabitation; and b) clinical variables, including body mass index (BMI), level of physical activity, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, dyslipidemia, peripheral and cerebral vascular disease, lung disease, type of renal replacement therapy and start date.

Assessment of frailty and functional capacityFrailty was evaluated by using the physical frailty phenotype defined by Fried et al.6 The FRIED scale includes the following 5 components: weight loss (unintentional weight loss ≥4.5 kg in the prior year), weakness (handgrip strength below a threshold according to sex and body mass index), exhaustion (self-reported), low physical activity (weekly kilocalories below an established threshold) and slowness in gait (time to travel 4.5 m below a threshold according to sex and height).

The assessment of frailty was performed at the first visit to the outpatient consultation for access to KT. Each of the 5 components is scored as 0 or 1 (according to the absence or presence of the specific component), and the final score is calculated as the sum of all of the items.

Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the FRIED score: 0 (a group of robust patients) and FRIED > 0 (a group of patients with some degree of frailty), due to the fact that our research group has demonstrated that prefrail patients on the waiting list exhibit worse pretreatment outcomes,7 as well as posttransplant outcomes.8

The evaluation of the degree of dependence for basic activities of daily living (BADL) was performed via the Barthel index, considering some degree of dependence for results below 100 points.12,13

The evaluation of the degree of dependence for instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) was performed via the Lawton and Brody scale, considering some degree of dependence for results lower than 5 points in men and 8 points in women.14

Measurement of patient-reported outcomesTwo questionnaires recommended by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes (ICHOM) for the standard set of ERC were administered.15 The results of the questionnaires were normalized by using a T score, wherein 50 represents the mean value and 10 represents the standard deviation according to the reference population (validated in the general population of the United States).16

The following 2 questionnaires were administered. a) PROMIS-Global Health®, which evaluates perceived general health through 10 items and provides summary scores for 2 domains (physical health and mental health). A T score of these domains greater than 45 is considered to represent a normal status. Moreover, a T score between 40 and 45 indicates mild impairment, a score between 30 and 40 indicates moderate impairment, and a score less than 30 is considered to indicate a severe status compared with the reference population. b) PROMIS-29®, which measures the following 7 domains: depression, anxiety, physical function, effects of pain, fatigue, sleep disorders and ability to participate in social functions and activities. In the PROMIS-29®, the domains of physical functioning capacity and the ability to participate in social roles and activities are scored in the same manner as those in the PROMIS-Global Health®: normal (T score >50), mild impairment (T score of 40–50), moderate impairment (T score of 30–40) and severe impairment (T score <30). In contrast, in the domains of fatigue, anxiety, sleep disturbance, depression and the effects of pain, the interpretation of the score is reversed: a T score <50 is considered to be normal, a T score of 50–60 indicates mild symptoms, a T score of 60–70 indicates moderate symptoms, and a T score >70 indicates severe symptoms. In the case of pain, the questionnaire evaluates how pain causes interference in the daily life of the patient and not specifically the intensity of the pain; thus, higher scores reflect a greater negative impact of pain on daily activities.

Data collectionThe sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected by reviewing the clinical histories of the participants, and the frailty and dependence scales were administered during the first visit to the outpatient clinic for access to KT.

The variables related to the PROMs were obtained by administering the 2 questionnaires via electronic devices. After their first visit to the KT access consultation, patients received a link via text message (SMS) to complete the PROMIS-Global Health® and PROMIS-29® questionnaires.

Data analysisIn the descriptive analysis, the variables with a normal distribution are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and the variables with a nonnormal distribution are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). In the comparative analysis of the characteristics between the groups, the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was applied to analyze the categorical variables. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, the Student’s t test w and the Mann–Whitney U test were used for nonparametric continuous variables. The relationship between frailty and the results of the PROMIS was determined by comparing the means of the T scores of each domain of the group of robust patients with those of the group of patients with some degree of frailty.

To evaluate the associations between the physical function domain of the PROMIS-29® questionnaire, frailty and other comorbidities, a multivariate analysis was performed by using binary logistic regression.

Statistical analysis was performed by using the statistical package SPSS® version 28 (IBM). Furthermore, p values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

ResultsThis study included 139 KT candidates who were evaluated by KT access consultation.

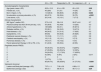

The mean age of the participants was 63.5 (±13.3) years, and 32.4% were women. The majority of the participants were born in Spain (80.6%) and lived with more people in their home (85.6%). A total of 47.5% of the participants demonstrated a lack of education or primary education. At the time of evaluation, 43.9% of the patients were receiving dialysis. With respect to frailty, 64.7% exhibited some degree of frailty (FRIED > 0) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the entire study population.

| All n = 139 | Responded n = 99 | No response n = 40 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 63.5 ± 13.3 | 61.4 ± 125 | 65 ± 15.3 | 0.05 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 45 (324) | 31 (31) | 14 (35) | 0.6 |

| Born in Spain, n (%) | 112 (80.6) | 86 (86.9) | 26 (65) | 0.003 |

| No education or primary education, n (%) | 66 (47.5) | 36 (36.4) | 30 (75) | <0.001 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 20 (14.4) | 13 (13.1) | 7 (17.5) | 0.5 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| IMC (kg/m2, media ± DE) | 27.3 ± 5.5 | 28 ± 5.9 | 26.27 ± 4.6 | 0.7 |

| Physical activity less than 30 min per day, n (%) | 55 (39.6) | 42 (424) | 13 (325) | 0.3 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 129 (928) | 94 (5.1) | 35 (87.5) | 0.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 53 (38.1) | 34 (34.3) | 19 (47.5) | 0.1 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 48 (34.5) | 31 (31.3) | 17 (425) | 0.2 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 89 (64) | 64 (64.6) | 25 (625) | 0.8 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 15 (10.8) | 11 (11.1) | 4 (10) | 0.8 |

| Cerebral vasculopathy, n (%) | 16 (11.5) | 13 (13.1) | 3 (7.5) | 0.3 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 19 (13.7) | 15 (15.2) | 4 (10) | 0.4 |

| Renal replacement therapy in HD or PD, n (%) | 61 (43.9) | 39 (39.4) | 22 (55) | 0.9 |

| Fragilidad (escala FRIED) | ||||

| 0 | 49 (35.3%) | 40 (40.4%) | 9 (225%) | |

| 1 | 47 (33.8%) | 35 (35.4%) | 12 (30%) | |

| 2 | 34 (24.5%) | 17 (17.2%) | 17 (425%) | |

| 3 | 8 (5.8%) | 6 (6%) | 2 (5%) | 0.017 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | |

| >0 | 90 (64.7%) | 59 (59.6%) | 31 (77.5%) | <0.001 |

| Valoración funcional | ||||

| Lawton and Brody test (average ± SD) | 7.37 ± 1.1 | 7.58 ± 0.9 | 6.88 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Barthel test (average ± SD) | 99 ± 5.1 | 98.78 ± 6 | 99.7 ± 1.5 | 0.04 |

SD: standard deviation; PD: peritoneal dialysis; HD: hemodialysis; BMI: body mass index.

The numbers in bold indicate significant p values.

Of the 139 participants who were included in this study, 28.7% did not answer the administered PROM questionnaires.

Sociodemographic, clinical and frailty characteristicsWhen comparing the group of people who responded to the PROM questionnaires with the group of people who did not respond, the group of responders was younger (61.4 ± 12.5 years vs. 65 ± 15.3 years; p = 0.05), had a higher educational level (75% vs. 36.4% with higher education; p < 0.001) and involved a lower percentage of people born outside of Spain (13.1% vs. 35%; p = 0.003). No differences were observed in comorbidities or dialytic modality.

The nonresponder group demonstrated a higher level of frailty compared to the group that responded to the questionnaire (77.5% vs. 59.6%; p = 0.04). When we compared the functional statuses of both groups, the candidates who did not answer the questionnaire were more dependent on performing BADL (Barthel: 98.7 ± 6 vs. 99.7 ± 1.5; p = 0.04) and IADL (Lawton-Brody: 6.8 ± 1.5 vs. 7.5 ± 0.9; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

The main causes of nonresponses included advanced age without technological access (n = 18; 45%) and language barriers (n = 12; 30%), with the remainder (n = 10; 25%) being attributed to different logistical problems (such as a lack of internet access or mobile device failures) not related to health.

Results of patient-reported outcome measuresIn the overall analysis of the results of the PROMIS-Global Health® questionnaires, the T score for the physical domain was 42.8 (±7.3), and the T score for the mental domain was 48 (±7.4). Only the T score of the physical domain was below the mean of the reference population, whereas the mental domain was reported as being good, with the pain domain considered to be low (Fig. 1).

In the results reported with the PROMIS-29®, the domains of effects of pain (50.2 ± 9), ability in social activities (53.7 ± 9.1) and anxiety (50 ± 8.6) were within normal limits compared with those of the general population (Fig. 2A). The domains of fatigue (47.1 ± 9.4), sleep disturbance (48.4 ± 7.5) and depression (48.4 ± 2.8) were also within normal ranges (Fig. 2B).

Moreover, the candidates reported a worse perception of their health only in the physical domain of the PROMIS-29® (46.1 ± 9.3) compared with the reference population.

Frailty and functional capacityThe mean age was similar between the group of robust patients and the group of patients who exhibited some degree of frailty (FRIED > 0) (61 ± 13.4 vs. 62 ± 11.3 years; p = 0.9). No differences were detected in the proportion of women (32.5% vs. 30.5%; p = 0.8), people born outside of Spain (15% vs. 11.9%; p = 0.6), people without education or with primary education (35% vs. 37.3%; p = 0.9), or regarding the scenario of SRRD through dialysis (40.7% vs. 37.5%; p = 0.7). No differences were observed in the remaining comorbidities.

Regarding the level of autonomy to perform BADL, the group of frail candidates exhibited worse scores on the Barthel index (98.1 vs. 100; p = 0.003) and worse scores on the Lawton and Brody scale (7.4 ± 1 vs. 7.8 ± 0.5; p < 0.001) compared with the group of robust patients.

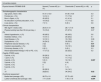

Results of patient-reported outcome measures according to frailty statusWith respect to the results of the PROMIS-Global Health®, only the physical domain differed between the two groups; specifically, frail candidates reported a worse perception of their physical health status compared with robust candidates (41.5 ± 1 vs. 44.7 ± 6; p = 0.03). No differences were observed in the results of the mental domain or in the pain domain.

Regarding the results of the PROMIS-29®, of the 7 evaluated domains, differences were only observed in the domain of physical function. Frail candidates reported worse perceptions of their physical function than nonfrail candidates (44.3 ± 10 vs. 48.8 ± 7.6; p = 0.001). In the remaining evaluated domains, the scores for pain interference, social activity capacity, fatigue, anxiety, sleep disturbance, depression and pain were similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

PROMIS results according to frailty status.

| All (n = 99) | Not frail (n = 40) | Frail (n = 59) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 61.4 ± 125 | 61 ± 13.4 | 62 ± 11.3 | 0.9 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 31 (31) | 13 (32.5) | 18 (30.5) | 0.8 |

| Born in Spain, n (%) | 86 (86.9) | 34 (85) | 52 (88.1) | 0.6 |

| No education or primary education, n (%) | 36 (36.4) | 14 (35) | 22 (37.3) | 0.9 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 13 (13.1) | 6 (15) | 7 (11.8) | 0.8 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| IMC (kg/m2, media ± DE) | 28 ± 5.9 | 26.6 ± 3.5 | 28.5 ± 6. | 0.3 |

| Physical activity less than 30 min per day, n (%) | 42 (42.4) | 13 (32.5) | 29 (49.1) | 0.1 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 94 (5.1) | 38 (95) | 56 (94.9) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 34 (34.3) | 13 (32.5) | 21 (35.6) | 0.7 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 31 (31.3) | 11 (27.5) | 20 (33.9) | 0.5 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 64 (64.6) | 28 (70) | 36 (61) | 0.3 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 11 (11.1) | 6 (15) | 5 (8.5) | 0.3 |

| Cerebral vasculopathy, n (%) | 13 (13.1) | 3 (7.5) | 10 (17) | 0.1 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 15 (15.2) | 7 (17.5) | 8 (13.5) | 0.5 |

| Renal replacement therapy in HD or PD, n (%) | 39 (39.4) | 15 (37.5) | 24 (40.7) | 0.7 |

| Fragilidad (escala FRIED) | ||||

| 0 puntos, n (%) | 40 (40.4) | 40 (100) | – | |

| 1 punto, n (%) | 35 (35.4) | – | 35 (59.3) | |

| 2 puntos, n (%) | 17 (17.2) | – | 17 (28.8) | |

| 3 puntos, n (%) | 6 (6) | – | 6 (10.2) | |

| 4 puntos, n (%) | 0 | – | 0 | |

| 5 puntos, n (%) | 1 (1) | – | 1 (1.7) | |

| PROMIS-Global-Health® | ||||

| Global Physical (average ± SD) J | 42.8 ± 7.3 | 44.7 ± 6 | 41.5 ± 1 | 0.03 |

| Global Mental Health (average ± SD) J | 48 ± 7.4 | 48.5 ± 7 | 47.6 ± 7.6 | 0.5 |

| PROMIS-29® | ||||

| Pain interference (mean ± SD) k | 50.2 ± 9 | 49.4 ± 8.6 | 50.8 ± 9.1 | 0.3 |

| Ability in social activities (average ± SD) k | 53.7 ± 9.1 | 55 ± 8.6 | 52.7 ± 9.3 | 0.1 |

| Physical function (mean ± SD) k | 46.1 ± 9.3 | 48.8 ± 7.6 | 44.3 ± 10 | 0.01 |

| Fatigue (mean ± SD) k | 47.1 ± 9.4 | 45.6 ± 9.2 | 48.1 ± 9.5 | 0.2 |

| Anxiety/fear (mean ± SD) k | 50 ± 8.6 | 49.4 ± 9 | 50.5 ± 8.3 | 0.4 |

| Sleep disturbance (mean ± SD) k | 48.4 ± 7.5 | 48.4 ± 9.2 | 48.3 ± 6.1 | 0.9 |

| Depression/Sadness (mean ± SD) k | 48.4 ± 2.8.1 | 48.6 ± 9.2 | 48.4 ± 7.5 | 0.8 |

| Effects of pain (mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 2.3 | 3 ± 2.1 | 3.4 ± 2.5 | 0.6 |

| Valoración funcional | ||||

| Barthel test (average ± SD) | 98.78 ± 6 | 100 ± 0 | 98.1 ± 7.3 | 0.003 |

| Lawton and Brody test (average ± SD) | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 1 | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; PD: peritoneal dialysis; HD: hemodialysis; BMI: body mass index.

Data in bold indicate statistically significant p values.

With the aim of identifying the factors associated with a worse perception of physical function, we compared patients with normal scores in the physical domain of the PROMIS-29® (T score > 45) with those who reported decreased physical function (T score <45). Patients with worse physical function exhibited a higher BMI (28.7 ± 7.1 vs. 26.8 ± 4.1; p = 0.03), as well as peripheral vascular disease (9.1% vs. 2%; p = 0.01) and more cerebral vasculopathy (10.1% vs. 3%; p = 0.002). They also demonstrated lower scores in both the Barthel index (97.8 ± 8.3 vs. 99.7 ± 1.8; p < 0.001) and the Lawton and Brody scale (7.4 ± 1.2 vs. 7.7 ± 0.6; p = 0.004). In this group, there was also a greater percentage of patients with some degree of prefrailty/frailty observed (34.3% vs. 25.3%; p = 0.02) (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, peripheral vascular disease and prefrailty/frailty (FRIED > 0) were the 2 independent factors associated with decreased physical function according to the PROMIS-29® (Table 3).

Results according to the physical function score in the PROMIS-2.

| Univariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical domain PROMIS-29 ® | Normal (T score>45) (n = 51) | Disminuido (T score<45) (n = 48) | p |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 61.01 ± 13.9 | 61.85 ± 10.9 | 0.3 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 14 (14.1) | 17 (17.2) | 0.7 |

| Born in Spain, n (%) | 45 (45.5) | 41 (41.4) | 0.1 |

| No education or primary education, n (%) | 19 (19.2) | 17 (17.2) | 0.8 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 7 (7.1) | 6 (6.1) | 0.8 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| IMC (kg/m2, media ± DE) | 26.8 ± 4.13 | 28.7 ± 7.15 | 0.03 |

| Physical activity less than 30 min per day, n (%) | 15 (15.2) | 27 (27.3) | 0.07 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 48 (48.5) | 46 (46.5) | 0.6 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 14 (14.1) | 20 (20.2) | 0.1 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 12 (12.1) | 19 (19.2) | 0.08 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 34 (34.3) | 30 (30.3) | 0.6 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 2 (2) | 9 (9.1) | 0.01 |

| Cerebral vasculopathy, n (%) | 3 (3) | 10 (10.1) | 0.02 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 6 (6.1) | 9 (9.1) | 0.3 |

| Renal replacement therapy in HD or PD, n (%) | 17 (17.2) | 22 (22.2) | 0.2 |

| Fragility (FRIED scale) | |||

| 0 points, n (%) | 26 (26.3) | 14 (14.1) | |

| 1 point, n (%) | 18 (18.2) | 17 (17.2) | |

| 2 points, n (%) | 5 (5.1) | 12 (12.1) | 0.007 |

| 3 points, n (%) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | |

| 4 points, n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 points, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| 0 | 26 (26.3) | 14 (14.1) | |

| >0 | 25(25.3) | 34 (34.3) | 0.02 |

| Functional assessment | |||

| Barthel test (average ± SD) | 99.75 ± 1.8 | 97.75 ± 8.3 | <0.001 |

| Lawton and Brody test (average ± SD) | 7.71 ± 0.64 | 7.44 ± 1.16 | 0.004 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| IMC (kg/m2) | 1.06 | 0.96–1.16 | 0.20 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5.96 | 1.63–9.28 | 0.012 |

| Cerebral vasculopathy | 3.02 | 0.67–13.65 | 0.15 |

| FRIED > 0 | 2.56 | 1.01–6.49 | 0.04 |

| Barthel Test | 0.94 | 0.81–1.09 | 0.44 |

| Lawton and Brody Test | 1.09 | 0.57–2.09 | 0.78 |

CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; OR: odds ratio.

Data in bold indicate statistically significant p values.

This study analyzed the perceptions of the health statuses of patients with advanced CKD who were candidates for KT through the application of PROMs, as well as the association of PROMs with comorbidities and frailty in particular. Compared with robust patients, frail or prefrail patients perceived a worse state of physical health. In contrast, no differences were detected in other dimensions, such as mental health, pain or emotional well-being.

In recent decades, progress has been made toward person-centered health care models, wherein patients’ opinions play a central role in clinical decision-making. In this context, PROMs have been consolidated as fundamental tools to capture subjective aspects of health status that are not reflected in traditional clinical measures, such as quality of life, level of autonomy or symptom burden.8,10 For this reason, interest in the implementation of PROMs in different health care settings is increasing,17 with the ultimate goal of complementing and improving clinical outcomes, including patient survival.18 In patients with advanced CKD, PROMs should function as a priority tool to improve the quality of life, as well as morbidity and mortality, of renal patients, given the high burden of symptoms experienced by this population.19

Currently, there is no consensus on the use of PROMs in the population with CKD. The ICHOM ERC working group15 has proposed 2 questionnaires (the PROMIS-Global Health® and PROMIS-29® questionnaires) as part of the standard set to evaluate the results reported by patients.20,21 The latest KDIGO guidelines also recommend the use of these 2 PROMIS questionnaires in renal patients.1

In this study, the response rate to the PROM questionnaires was 71.2%, which is similar to that reported in the literature for self-administered telematic surveys.22 Nonresponses were associated with age-related technological barriers23 and language difficulties.24 A lower educational level and a higher proportion of foreign patients represented factors associated with lower response rates.25,26

To address these limitations, various strategies have been proposed. One of the most prominent strategies involves the use of hybrid models, which combine digital versions with paper forms or face-to-face interviews, thus facilitating the participation of people of advanced age or with little digital literacy.27–29 Other effective measures to improve implementation in special populations include offering assistance during completion, simplifying the content of the questionnaires and sending personalized reminders.30–32 To address language barriers, the translation and cultural adaptation of PROMs to different languages is recommended, involving patients from the target population in their validation.33 The PROM coordinators can also represent a key facilitating element for a more inclusive implementation.29,34

The perceptions of the physical conditions of the TR candidates included in this study were deteriorated, as assessed with both PROMIS questionnaires. In the PROMIS-Global Health®, the mental domain demonstrated scores within the mean, whereas the physical domain demonstrated scores below the values of the general population. Similarly, in the PROMIS-29®, physical function was the only domain demonstrating scores below the mean, whereas the remaining domains (anxiety, fatigue, pain, sleep and social ability) remained within normal ranges. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies conducted in older patients with chronic diseases,35 including advanced CKD, in which physical function systematically represents the most altered domain.36 Similarly, when the PROMIS is administered to TR patients, the physical domain demonstrates the worst score, followed by depression and sleep disturbance.37

Experience in the use of PROMIS questionnaires among transplant candidates is still very limited. In a recent publication involving 154 KT candidates, patients who reported worse PROMIS scores before KT visited the emergency room more often and experienced more readmissions during the first month after KT.38 Another study conducted in liver transplant candidates also revealed an association between a lower physical function score on the PROMIS-29®, greater frailty measured via the Liver Frailty Index scale and hospitalization rate during the waiting list period.39

Frailty is a determining factor in access to KT5 and in posttransplant results.7 In our study population, the prevalence of frailty or prefrailty was 64.7%, and candidates with FRIED scores > 0 reported a worse perception of their physical state in both the PROMIS-Global Health® and the PROMIS-29®; however, these scores did not differ across the other domains. In our cohort of patients, the worst perception of physical function reported by the patient was independently associated with prefrailty/frailty, and peripheral vascular disease was the only disease that was independently associated with a low T score in the PROMIS-29®.

The association between frailty and the worst self-perception of physical state observed in our results reinforces the usefulness of PROMs as a complementary tool in the functional evaluation of KT candidates. In addition, this association could suggest a specific impact of frailty on the self-perceived physical dimension, which would be consistent with the pathophysiology of frailty (which is focused on the loss of physical and functional reserves). The implementation of PROMIS could contribute to differentiating among subgroups within the set of frail patients, thus allowing for a more precise stratification and facilitating personalized interventions. Moreover, the standardization of PROMs should be prioritized for use in this group of patients, with the aim of improving the evaluation and comparison of interventions for frailty.40

The main limitations of this study include its retrospective and cross-sectional design, which prevents the establishment of causal relationships or the investigation of the temporal evolution of PROMs and their impacts on access to KT or on posttransplant outcomes. In addition, the sample is not completely representative of the population on the waiting list, because the characteristics of those individuals who did not respond to the questionnaires differ from those who did respond.

In conclusion, the PROMs represent a valuable tool for evaluating the subjective perception of the health statuses of patients who are candidates for KT. The implementation of these instruments in daily clinical practice could facilitate strategies aimed at improving health outcomes, optimizing follow-up on the waiting list and improving access to transplantation. In addition, the standardization and validation of specific PROMs for this population (with a special focus on frail or prefrail patients) will improve the comparability of studies and their applicability in different clinical contexts.

ORCID IDAnna Bach-Pascual: 0000-0003-0571-6131

Clara Amat-Fernández: 0000-0001-9595-0970

Guillermo Pedreira-Robles: 0000-0002-6180-4059

Betty Chamoun-Huacon: 0000-0002-4267-2273

Olatz Garin: 0000-0001-6193-0779

Yolanda Pardo: 0000-0003-4982-5495

Erica Briones-Vozmediano: 0000-0001-8437-2781

Esther Rubinat-Arnaldo: 0000-0003-0232-9777

Marta Crespo-Barrio: 0000-0002-1852-2259

María José Pérez-Sáez: 0000-0002-8601-2699

CRediT authorship contribution statementDolores Redondo-Pachón and Anna Bach-Pascual share first authorship, and María José Pérez-Sáez and Guillermo Pedreira-Robles are the last authors.

FinancingThis study was conducted as part of the doctoral thesis of the author (Anna Bach-Pascual).

Clara Amat-Fernández is funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya, Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR FI-2 00266).

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

We acknowledge the individuals with CKD who selflessly participated in this study.