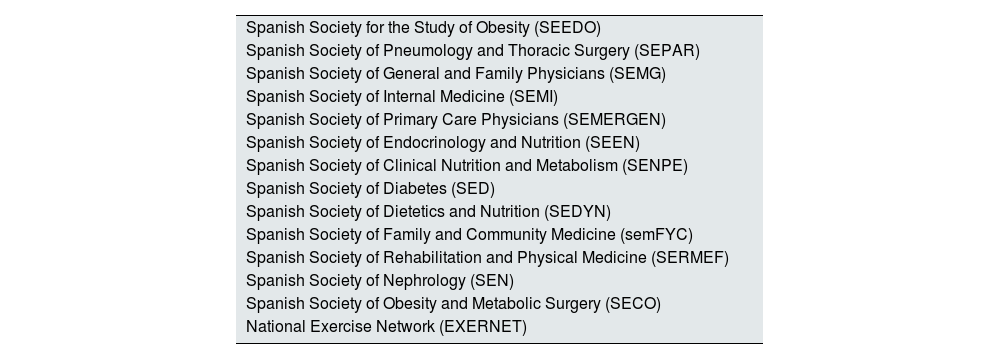

The second edition of GIRO, an acronym for the “Spanish Guide to the Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Management of Obesity in Adults”1,2 has recently been published. The Spanish Society of Nephrology is one of the 39 scientific societies that participated in its development (Table 1), highlighting the impact that excessive and dysfunctional adipose tissue can have on renal function. The guide aims to be a valuable tool for health care professionals and to influence those responsible for health policies, as well as all those committed to promoting the prevention and improving the treatment of obesity.

Societies participating in the creation of the GIRO guidelines.

| Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (SEEDO) |

| Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) |

| Spanish Society of General and Family Physicians (SEMG) |

| Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI) |

| Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN) |

| Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN) |

| Spanish Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (SENPE) |

| Spanish Society of Diabetes (SED) |

| Spanish Society of Dietetics and Nutrition (SEDYN) |

| Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (semFYC) |

| Spanish Society of Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine (SERMEF) |

| Spanish Society of Nephrology (SEN) |

| Spanish Society of Obesity and Metabolic Surgery (SECO) |

| National Exercise Network (EXERNET) |

This is a much-needed guide. On the one hand, the 18.7% of the Spanish population currently living with obesity is estimated to increase to 37.0% over the next 10 years. On the other hand, obesity constitutes the origin of cardiovascular-renal-metabolic syndrome, a health disorder resulting from the interconnections among obesity, metabolic risk factors, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular disease.3 Thus, a large number of patients with CKD live with obesity, a disease that may trigger deterioration of renal function or worsen its progression and prognosis.4,5 Although the classic definition of obesity refers to an increase in body fat mass, today it is accepted that this disease originates as a result of adipose tissue dysfunction caused by excessive or abnormal accumulation.6,7

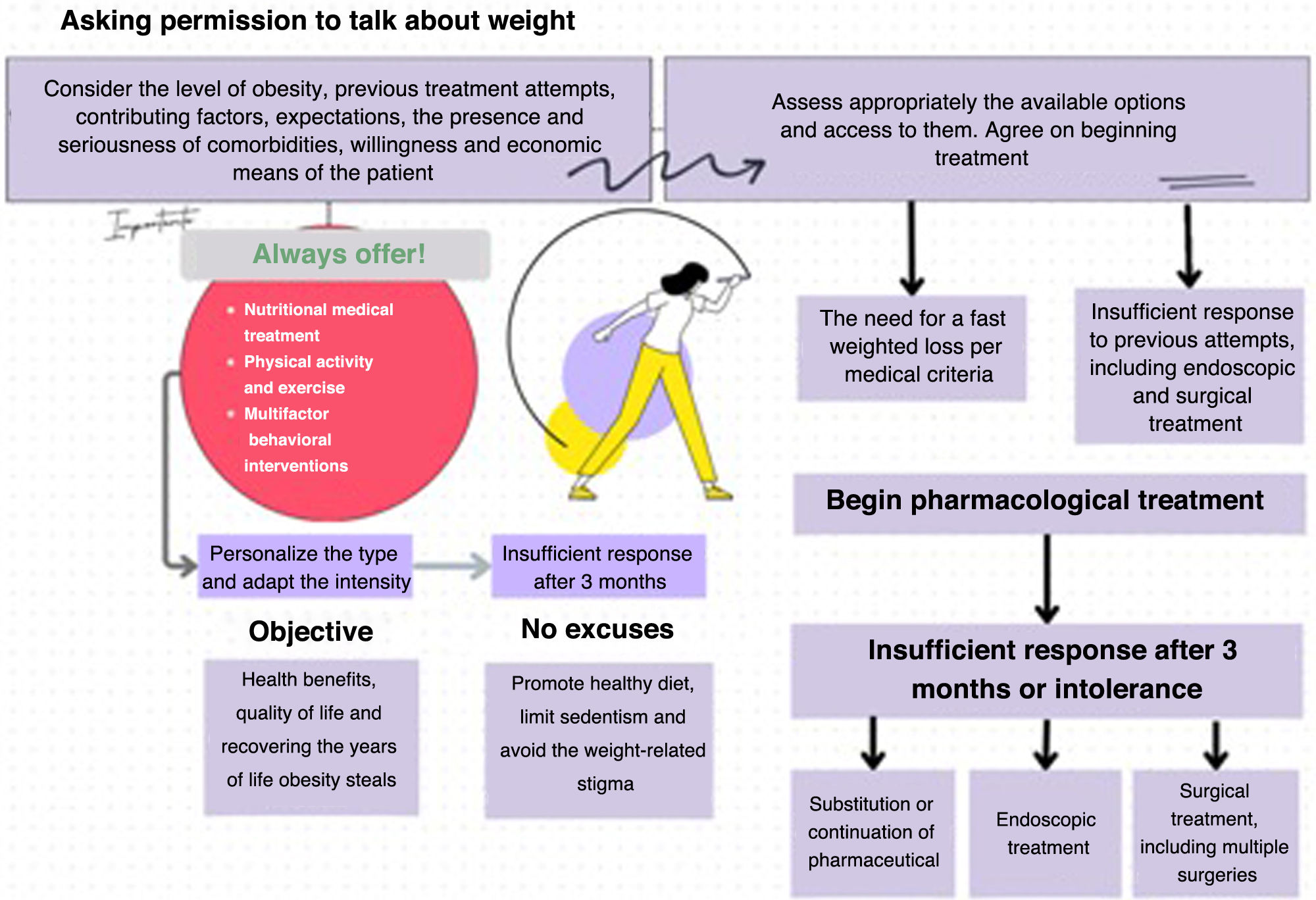

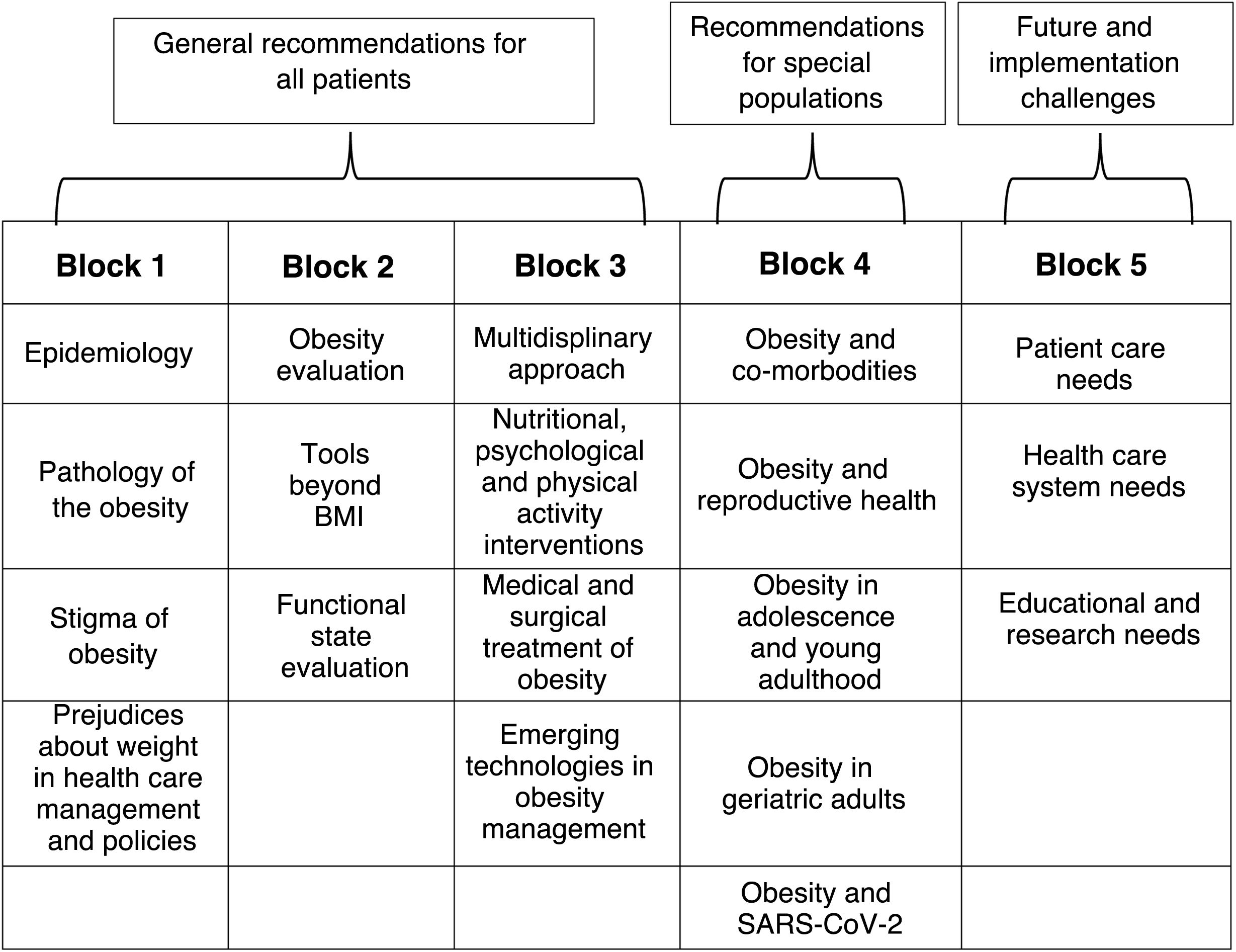

The GIRO guidelines, though inspired by the Canadian guidelines published in 2020, include the most recent and relevant evidence in our field on the best management and treatment of adult obesity.8 With the primary objective of proposing a change of approach in the management of the disease, the guideline aims to promote the approach to obesity as a chronic and complex disease, to reject the misconception that obesity is a moral failing and the solely the patient’s responsibility, to understand that we must move forward by starting to talk about “obesities” instead of “obesity,” to promote the inclusion and use in clinical practice of valid health indicators for measuring obesity that are not based solely on body mass index (BMI), to incorporate precision medicine in its management, and to propose the need for a holistic approach and a multidisciplinary approach.

In the assessment of obesity, the concept of nutritional ultrasound is increasingly being introduced, allowing the morphology and structure of muscle mass and adipose tissue to be analyzed in the clinical setting, with the advantages of being low-cost, portable, non-radiative and easy to learn. Structured ultrasound of abdominal adipose tissue allows differentiation between superficial and deep layers of subcutaneous fat, as well as examination of deeper layers, such as preperitoneal, omental (intraperitoneal) and perirenal (retroperitoneal) fat. All these types of fat are included in the concept of “visceral adiposity” and omental and perirenal fat deposits are considered predictors of metabolic complications.9,10

The GIRO guide details the mechanisms associated with obesity-related renal disease, delving into the hemodynamic pathway, the perirenal ectopic adipose tissue pathway (due to the compressive effect, local accumulation and the presence of inflammatory cytokines) and the insulin resistance pathway.5 It also highlights how arterial hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus amplify the negative effects of obesity on the renal parenchyma, which manifest as reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate or increased proteinuria, so that screening for CKD should be routinely performed in all patients with obesity.5

The authors of the GIRO guide, including the signatories of this editorial, deeply hope that its dissemination will facilitate synergies between professionals and specialties, which will also help to correctly identify patients with obesity in order to offer them treatment free of stigma or inequity, to preserve the years and quality of life threatened by obesity and CKD.

The guidelines also draw the attention of health professionals to other obesity-related conditions of the renal apparatus, such as urinary stones, particularly uric acid lithiasis. Associated causes include insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, which increase urinary excretion of calcium and oxalate and reduce excretion of citrate, a natural inhibitor of stone formation. Other contributing factors include consumption of diets high in salt and protein, dehydration due to increased perspiration and decreased fluid intake, and chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity.4

Also highlighted in this guideline is how patients with obesity on kidney transplant waiting lists experience longer delays and are less likely to undergo transplantation than patients without obesity. Although in most clinical practice guidelines obesity is not considered a contraindication for renal transplantation, many centers consider a BMI > 35 kg/m2 a relative contraindication for this process.5 However, it is important to note that renal transplantation in patients with obesity offers better survival than permanent dialysis.5

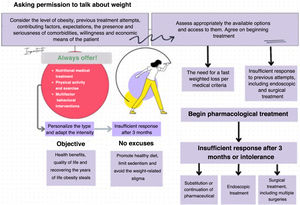

In recent decades, sufficient evidence has been generated to understand that obesity is not a disease caused only by alterations in individual habits.11 Currently, obesity is understood as a disease with a multifactorial etiology in which genetic, sociodemographic and environmental factors contribute to its development.11,12 The management of obesity in patients with CKD should be multidisciplinary and based on all the options currently available (nutritional therapy, physical activity, behavioral therapy, pharmacological options and bariatric surgery), with special preference for the strategies that have demonstrated the greatest renal benefit. The available evidence shows that pharmacological treatment for weight loss has renal protective effects, although the evidence is more limited regarding the effect of pharmacological treatment to treat obesity before renal transplantation.13–16

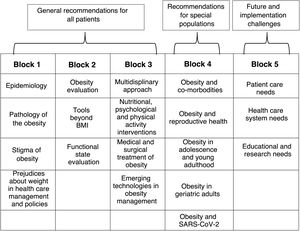

Finally, the GIRO guideline provides a total of 144 recommendations (Table 2): 31 of them literally translated from the Canadian guideline and applicable to Spain without the need for changes, and 113 elaborated based on newly available and evaluated evidence. The 3 recommendations related to CKD correspond to the latter group (Fig. 1): 1) screening for CKD should be promoted in patients with obesity by determining glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria; 2) the management of obesity and kidney disease should be multidisciplinary and should include weight loss strategies, behavioral modifications, pharmacological treatments, and, when appropriate, bariatric surgery; and 3) people with obesity and end-stage renal disease should not be excluded from renal transplantation because of their BMI, since survival after transplantation is greater than on dialysis. In all of them, the quality of the evidence and its strength, using the Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) system, were rated as “low” quality and “weak” strength, respectively.

We would like to thank all the scientific societies and their representatives that have collaborated in the development of the GIRO Guideline.