La enfermedad neumocócica invasiva (ENI) supone un grave problema en algunos grupos de riesgo: los pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica estadios 4 y 5 y aquellos con estadio 3 y tratamiento inmunosupresor, síndrome nefrótico o diabetes. Estos individuos son más susceptibles de adquirir la infección y más propensos a padecer cuadros de mayor gravedad y peor evolución. Entre las estrategias para prevenir la ENI se encuentra la vacunación, aunque las coberturas vacunales en este grupo son más bajas de lo deseable hoy en día. Actualmente, disponemos de dos vacunas para el adulto. La vacuna polisacárida (VNP23), que se emplea en mayores de 2 años de edad desde hace décadas, es la que mayor número de serotipos (23) incluye, pero no genera memoria inmunitaria, provoca un fenómeno de tolerancia inmunitaria y no actúa sobre la colonización nasofaríngea. La vacuna conjugada (VNC13) puede emplearse desde lactantes hasta la edad adulta (la indicación en mayores de 18 años ha recibido la aprobación de la Agencia Europea de Medicamentos en julio de 2013) y genera una respuesta inmunitaria más potente que la VNP23 frente a la mayoría de los 13 serotipos en ella incluidos. Las 16 sociedades científicas más directamente relacionadas con los grupos de riesgo para padecer ENI han trabajado en la discusión y elaboración de una serie de recomendaciones vacunales basadas en las evidencias científicas respecto a la vacunación antineumocócica en el adulto con condiciones y patología de base que se recogen en el documento «Consenso: Vacunación antineumocócica en el adulto con patología de base». En el presente texto se recogen las recomendaciones de vacunación para la población de enfermos renales crónicos.

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is a serious problem in some risk groups: patients with stage 4 and 5 chronic kidney disease, stage 3 CKD undergoing immunosuppressive treatment, nephrotic syndrome or diabetes. These individuals are more susceptible to infections and more prone to suffering more severe and worsening symptoms. Vaccination is one of the strategies for preventing IPD, although vaccination coverage in this group at present is lower than desired. Currently, there are two vaccinations for adults. The polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), used for decades in patients over the age of 2, includes most serotypes (23), but it does not generate immune memory, causing the immune tolerance phenomenon and it does not act on nasopharyngeal colonisation. The conjugate vaccine (VNC13) can be used from infancy until adulthood (advice in patients over 18 years old received approval from the European Medicines Agency in July 2013) and generates a more powerful immune response than PPSV23 against the majority of the 13 serotypes that it includes. The 16 scientific societies most directly associated with the groups at risk of IPD have discussed and drafted a series of vaccination recommendations based on scientific evidence related to pneumococcal vaccination in adults with underlying conditions and pathologies, which are the subject of the document “Consensus: Pneumococcal vaccination in adults with underlying pathology”. This text sets out the vaccination recommendations for the chronic kidney disease population.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the advances made with regard to haemodialysis (HD), both overall mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients who receive this type of therapy is much higher than in non-uraemic patients1. Renal replacement therapies such as haemofiltration, high-flux HD and haemodiafiltration (HDF) combine diffusion and convection with the objective of increasing clearance of uraemic toxins. Postdilutional online HDF (OL-HDF) is the most used convective therapy because it allows large replacement volumes to be obtained using the dialysate, resulting in maximum clearance of uraemic toxins, as well as good haemodynamic tolerance, thus reducing the complications associated with conventional therapy2-4. Since convection is the transport that is predominant in the glomeruli, it is considered to be a more “physiological”, safe and versatile technique because it allows large quantities of replacement fluid to be produced in situ5.

The addition of the replacement volume and the loss of intradialysis weight (ultrafiltration) constitute the total convective volume6. Total convective volume has been directly related to clearance of uraemic molecules, especially those of a medium and large size6-8.

Several studies suggest a link between convective volume and overall survival. Consequently, retrospective studies such as the European patient subgroup of the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Pattern Study and randomised studies such as the Turkish OL-HDF and CONTRAST studies have demonstrated the decrease in mortality with replacement volumes of 15, 17.4 and 20, respectively, in post-hoc analysis. The recent ESHOL study demonstrated higher survival in patients who received >23 l of total convective volume12.

The main limitation to achieving a high convective volume lies in blood flow (Qb) and haemoconcentration. In this regard, the new generation of dialysis machines has improved the software in terms of increasing the total convective volume, optimising infusion flows (Qi) in relation to intradialysis changes13. The ultracontrol system in the Gambro machines or the Fresenius 5008 CorDiax automated replacement system are technological advances that attempt to maximise the convective volume administered automatically.

Until present, use of the “automated manual” regimen was recommended, in which the values of haematocrit and total protein were modified manually on the monitor in order to optimise the Qi with the lowest number of alarms14.

The study’s objective was to evaluate the recent version of the 5008 monitor software (CorDiax) compared to that of the previous version on the impact on total convective volume.

PATIENTS AND METHOD

The study was carried out in a hospital in stable HD patients. We included 63 patients, 44 males and 19 females, with a mean age of 65.2 ± 15 years (interval of 26-88 years) who had been on a HD programme for an average of 46.6 ± 52.6 months. The chronic renal failure aetiology was as follows: chronic glomerulonephritis in 12 patients (19%), diabetic nephropathy in 11 (17.5%), polycystic kidney disease in 9 (14.3%), vascular in 6 (9.5%), renal tumour in 4 (6.3%), a urological cause in 2 (3.2%), a systemic cause in 1 (1.6%), tubulointerstitial nephritis in 1 (1.6%) and an unknown cause in 17 (27%). Most patients received dialysis via an arteriovenous fistula (81%) and the remainder, using a catheter (16%) or a polytetrafluoroethylene prothesis.

In the first stage, each patient was assessed over three sessions with a 5008 monitor before the change of software was implemented. In the second stage, we recorded three other OL-HDF sessions with the new update.

During the week in which the 5008 monitor was used, a Qi was administered using the automated manual regimen, adjusting the haematocrit and total protein to achieve and maintain the Qi prescribed, which was approximately 25% of the Qb. During the second stage of the study, with the new version of the monitor, we used the automated infusion system, in which it was not necessary to introduce any value.

We considered the demographic characteristics of each patient: age, sex, time on dialysis, body surface area and body mass index. The dialysis parameters recorded in each session were: time scheduled, real time, dialyser, type of vascular access, blood flow, dialysate flow (Qd), heparin dose, Kt measured automatically by ionic dialysance, recirculation rate, arterial blood pressure, venous blood pressure, transmembrane pressure, initial and final haemoglobin, ultrafiltration, minimum plasma volume, processed blood volume and total convective volume.

In the laboratory, we determined haemoglobin, haematocrit and albumin at each stage.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS statistical software version 20.0 and the results were expressed as an arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. To analyse the statistical significance of quantitative parameters, we used Student’s t-test for paired data and the ANOVA test for repeated data. Values of p< 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

All dialysis sessions were carried out without notable clinical incidents and with a small number of monitor alarms. The dialysers used were: 1.4 m2 helixone in 76%, 1.8 m2 helixone in 19% and 2.1 m2 polyamide in 5%. Each patient had the same dialyser in both study periods. The anticoagulation used was heparin sodium in 6.4%, low-molecular-weight heparin (tinzaparin or nadroparin) in 79% and the remaining 14.3% sessions were carried out without heparin.

The dialysis time prescribed was 288.6 ± 17 min, the Qb was 400 ± 34 mL/min (interval between 300 and 450 mL/min) and the Qd 500 mL/min; we should bear in mind that this flow is that which is going to be processed for diffusion and the Qi is additional.

There were no statistically significant differences in the laboratory parameters, the real dialysis time, the Qb or other dialysis parameters (Table 1). The only exception was the ultrafiltration volume: 2.25 l ± 0.92 with the 5008 monitor versus 2.06 l ± 0.85 with the CorDiax monitor (p = 0.005). Arterial pressure, venous pressure and transmembrane pressure were similar in both study periods, as well as the recirculation rate, the processed blood volume and the dialysis dose measured by ionic dialysance and expressed as Kt (Table 1).

The replacement volume was significantly higher with the 5008 CorDiax monitor: 31.2 ± 3.4 l, versus the 5008 monitor: 27.2 L ± 2.8, p< 0.001. These differences are maintained when we separate the sessions into the three days of the week (Figure 1). Table 2 also displays the absolute total convective volume, as well as volume related to dry weight, body surface area and body mass index and lastly the effective convective volume percentage of the total processed blood, with the differences being significant in all cases. Patients with a catheter received a replacement volume below that of those with fistulas; however, upon changing to the 5008 CorDiax monitor, there was a significant increase in the replacement volume in patients with fistulas and those with tunnelled venous catheters (Figure 2).

The replacement volume increase was maintained regardless of the dialyser used, 27.43 ± 2.5 versus 31.38 ± 3.2 l with 1.4 m2 helixone, 27.47 ± 2.6 versus 31.71 ± 3.0 with 1.8 m2 helixone, and 26.08 ± 4.9 versus 31.57 ± 5.8 with 2.1 m2 polyamide (p< 0.001 in all cases).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that it is possible to increase the total convective volume with postdilution OL-HDF with the only change being the new dialysis machine software, without modifying any of the other dialysis parameters.

OL-HDF is a safe technique that improves intradialysis haemodynamic tolerance15. Currently, the ESHOL study has contributed scientific evidence that patients who receive postdilution OL-HDF have increased survival compared those on HD12. A subsequent meta-analysis that includes the three main randomised multi-centre studies10-12 has confirmed that OL-HDF reduces overall mortality by 16%16. These data lead us to predict a progressive increase in this technique, and it will probably become the standard treatment in the near future.

However, there are still issues to be resolved with regard to HDF techniques. The first is a conceptual redesign. According to the Eudial group, HDF is a blood clearance treatment that combines diffusive and convective transport using a high-flux dialyser with the following characteristics: an ultrafiltration coefficient greater than 20 mL/mmHg/h/m2 and a screening coefficient for ß2-microglobulin greater than 0.6. It is considered that the minimum effective convective transport percentage must be greater than 20% of the total blood processed6.

A second issue to discuss is what the adequate convective volume should be per session. In a post-hoc analysis that assessed mortality in relation to the convective volume received, in the three randomised clinical trials, there was superiority in receiving a high convective volume. In the Turkish study, when we analysed the patients by the median reinfusion volume, 17.4 l, we found a 46% reduction in mortality10. In the CONTRAST and ESHOL studies, the analysis was carried out separating patients into terciles and they found a reduction in mortality when they received a total convective volume greater than 22 and 23 L, respectively. Logically, since it was a secondary analysis, there was a selection bias, since the patients who achieved a higher convective volume could be younger, with better vascular access and lower comorbidity11,12.

The main limiting factors in achieving high convective volumes were Qb, time and haemoconcentration in the dialyser. In recent years, there has been technological development with the aim of achieving an increase in convective volume. New dialysers were developed with an increased pore size and some were developed with an increase in the diameter of the capillary fibres specifically designed to increase the convective volume. The other advancement corresponded to the development of new dialysis monitors that allow an automated Qi in order to maximise the convective volume. The 5008 CorDiax monitor software update is based on the dynamic analysis of the pressure pulse signals that are generated when blood passes through the filter, and using an internal algorithm, the machine automatically regulates the Qi to the highest possible volume at each moment. This system, known as AutoSub plus, uses the already existing signals of pressure pulses created continuously by rotation of the blood pump, venous blood pressure and transmembrane pressure. The frequency and amplitude of these signals are measured by the venous pressure sensor, allowing analysis of stress in the dialyser capillary dynamically, and optimising continuously the Qi administered.

As for haemoconcentration, there is a difference between haematocrit and albumin levels. In an analysis of the factors that determine the convective volume carried out in the CONTRAST17 study, there was an inverse relationship between haematocrit levels and the convective volume; however, they found a direct correlation with pre-dialysis albumin values (there was an increase of 1 l of convective volume per session for each 10 g/l of albumin). It seems that, a higher albumin value increases oncotic pressure and facilitates increased vascular filling.

It is important to distinguish between the convective volume in the predilution, postdilution, mid-dilution or mixed reinfusion method. The postdilution technique is that which has been most effective in clearing uraemic toxins of a small and medium size18-21. The main limitation in using this technique would be the intra-filter haemoconcentration that occurs and as the HD session passes, the polarisation phenomenon increases (accumulation of plasma proteins) which blocks the membrane pores, increasing the transmembrane pressure necessary to produce ultrafiltration, which decreases the effectiveness of the technique and may cause coagulation of the circuit22. The new dialysis machines with automated infusion systems have minimised haemoconcentration problems and the number of alarms, which has maximised the convective volume. This study is a clear example of the technological advancement and it shows that the reinfusion volume may increase between 3 and 4 l per session with an automated continuous Qi control system.

Achieving adequate convection volumes (probably higher than 21 l per session) may be complicated in patients with limited blood flow (patients with catheters or malfunctioning vascular access). Some studies have achieved high ultrafiltration volumes using monitor optimisation systems. For example, the Gambro® ultracontrol system in some studies allowed a higher convective volume to be achieved13 and in others, an increase in the filtration fraction by more than 30%23. Moreover, in the previous Fresenius 5008 monitors, to maximise the infusion rate, use of the automated manual regimen was recommended, which consisted of maintaining the automatic infusion of the Qi, achieving the initial regimen by modifying the protein and/or haematocrit monitor values, which achieved an increase in the Qi with a lower number of alarms14; in this study, in one of the four sessions, the Qi was forced to 20 mL/min and a 2.2 l increase was achieved in the replacement volume (half of the current version). The new 5008 CorDiax version simplifies the process with a fully automated infusion system which, as this study shows, has achieved an increase in the convective volume.

Another aspect that has not yet been resolved is the way in which to express convective volume. We should express it in litres per session in absolute terms or relative to dry weight, by body surface area, by body mass index or, as was mentioned previously by the EuDial group, by the percentage of total filtered blood. In this study, considering that the average dialysis duration was almost five hours, the total convective volumes achieved were high, regardless of how we express them, and a significant increase was observed with the new software. The replacement volume increased from 5.3 L/h to 6.17 l/h, with the effective convective volume percentage increasing from 26.1% to 29.6% of total filtered blood. This significant difference may be important in patients who carry out short OL-HDF sessions or in those in which the Qb is limited.

The convection dose continues to be the major issue to be resolved in the coming years, and it is currently recommended that a total convective volume greater than 21 l per session should be achieved, based on the post-hoc analysis results of the main clinical trials, in the absence of more conclusive scientific evidence.

CONCLUSION

The change of software in the 5008 dialysis monitor has meant a 13% increase in the total convective volume. The effective convective volume percentage of total processed blood increased by 3.5%. These results were achieved without differences in arterial, venous or transmembrane pressure. This technological advancement has allowed an increase in the convective volume per session, which could lead to optimum volumes being achieved in a greater number of patients.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Francisco Maduell has received fees as a Fresenius speaker.

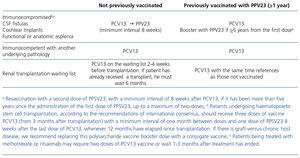

Table 1. Patients considered to be immunocompromised or immunocompetent with other underlying pathologies or risk factors

Table 2. Vaccination recommendations in adults with an underlying disease