Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a disorder secondary to deficiency in CD55 and CD59, two surface complement regulatory proteins, resulting in chronic complement-mediated haemolysis.1 Renal involvement ranges from acute kidney injury during hemolytic crisis, proximal tubular dysfunction (PTD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).2 Hemoglobinuria only occurs in 25% of patients,3 recent series have reported an incidence of 64% of ERC, with up to 20% of CKD stage 3–5.4

We present two HPN cases in which hemosiderin deposits visualized by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appear to be early signs of renal impairment.

Case 1Male of 41 years old, submitted for evaluation of proteinuria. Previously diagnosed of PNH in context of hemolytic anemia. It did not require blood transfusions and had no thrombotic events. Laboratory tests showed persistent hemolytic activity, elevated LDH (1800–3000U/L) and undetectable haptoglobin, hemoglobin of 8.5mg/dl, leucopenia and thrombocytopenia, mild normal ferritin of 25ng/ml.

He presented recurring haemolytic crisis with fatigue, dysphagia, abdominal pain and dark urine. The episodes usually lasted one to three days, every two or three months.

Renal function was normal, serum creatinine 0.9mg/dl and FG (MDRD)> 60ml/min. Persistent hemoglobinuria with normal urinary sediment. Proteinuria 1.3g/day with albuminuria 170mg/day and non-selective aminoaciduria, thus indicating PTD. The acid-base status, phosphate and uric acid were normal. The possibility of PTD due to hemosiderin deposition was considered, so an MRI was performed, finding hypointense bilateral renal cortical compatible with iron deposition (Fig. 1A and B). Eculizumab therapy was considered, but he was not eligible because lack of transfusion requirement, and normal GFR.

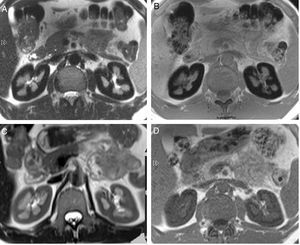

(A) Axial T2 sequence image. Diffuse low signal of the renal cortex compared to the liver and skeletal muscle. (B) Axial T1 in-phase sequence also shows low signal of the renal cortex compared to the liver and skeletal muscle. (C) MR of the same patient 14 months after start of treatment. Axial T2 sequence image shows important improvement of the low signal on T2. (D) Axial T1 in-phase sequence confirms the important increase of the renal cortex signal compared with the previous MR study.

Two years later, he presented a severe hemolytic crisis with acute renal failure, which was attributed to hemoglobinuria. The patient was treated conservatively, showing recovery of renal function in 18 days. After this episode start treatment with eculizumab. In a few weeks, the LDH and hemoglobin almost normalized, maintaining low levels of haptoglobin. In the following months, the tubular proteinuria gradually normalized.

Fourteen months after the start of eculizumab a new MRI showed improved hypointense signal in the renal cortex of 34% and 51% in the left and right kidney respectively, indicating the partial removal of iron deposits in the kidney (Fig. 1C and D).

Case 2Male of 40 years old, with newly diagnosed renal PNH referred for evaluation. In the previous nine months had repeated episodes of dark urine and lower back pain. He had severe hemolytic anemia, hemoglobin of 7.7mg/dl, undetectable haptoglobin, elevated LDH 3800U/L and requiring transfusion of red blood cells. Ferritin and transferrin saturation were normal. The renal function was normal, creatinine 0.8mg/dl, proteinuria of 427mg/24h, with albuminuria of 120mg/24h. Positive hemoglobinuria with normal sediment, negative glucosuria and normal fractional excretion of phosphate.

In the 10 months follow-up presented repeated hemolytic crisis, with gross hemoglobinuria. He reported difficulty to concentrating and recurrent headache. An MRI showed a marked hypointense signal in the renal cortex in all sequences (Fig. 2A and B) and a brain MRI revealed multiple subcortical lacunar lesions. Due to the cerebral involvement attributable to PNH eculizumab treatment was started.

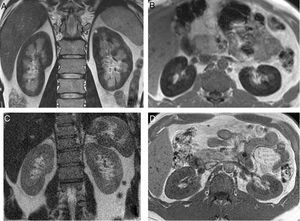

(A) Coronal T2 sequence image. Diffuse low signal of the renal cortex suggesting the presence of iron deposit. (B) Axial T1 in-phase sequence also shows low signal of the renal cortex compared to the liver and skeletal muscle. (C) MR of the same patient 17 months after start of treatment. Coronal T2 sequence image shows disappearance of the low signal on T2. (D) Axial T1 in-phase sequence also demonstrates normal intensity of the renal cortex.

The patient evolved without new hemoglobinuria crisis with resolution of anemia and normalization of LDH with persistent decreased haptoglobin level.

Seventeen months after the start of treatment a new IRM showed a normal intensity signal in the renal cortex (Fig. 2C and D). Renal function remained normal, with proteinuria 130mg/day and negative hemoglobinuria.

DiscussionThe accumulation of visceral iron produces a artifact which leads to signal loss in gradient echo sequences and T2. It is useful compare the signal of the renal cortex with skeletal muscle, if it is lower than the muscle, suggests the presence of visceral iron.5

The accumulation of hemosiderin generates oxygen free radicals leading to mitochondrial injury, with consequent deleterious effects on the apical and basolateral transport.6–8

Improvement in hypo intensity signal in the renal cortex indicates the decrease in the iron deposit.9,10 In our patients improved hypointense was accompanied by the recovery of tubular proteinuria. Hemosiderin deposits by MRI can be present previous to development of proteinuria (Case 2).

It has been reported that treatment with eculizumab was associated with an improvement in the degree of CKD after 18 months. This effect was more pronounced in patients with CKD stage 1–2, suggesting that therapy should be initiated early.11

In summary, we present two cases of PNH with renal involvement manifested as tubulointersticial proteinuria and hemosiderin deposits evidenced by MRI as the first manifestation.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Piñeiro GJ, Nicolau C, Gaya A, Buñesch L, Poch E. Rol de la resonancia magnética renal en la monitorización del aclaramiento de los depósitos de hemosiderina en la hemoglobinuria paroxística nocturna. Nefrologia. 2017;37:225–227.