Sustained low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) is an intermittent hybrid renal replacement modality in between conventional intermittent haemodialysis (IHD) and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).1 The superiority of continuous techniques compared to conventional intermittent techniques with regard to haemodynamic tolerance in critically ill patients has not been demonstrated,2,3 meaning that the choice of modality depends on the availability thereof and on the experience of the doctor the prescribe the modality of treatment. However, the clinical experience is that approximately two-thirds of IHD sessions in critically ill patients are not well tolerated,4 requiring the use of continuous techniques.

We present the experience of using SLED in a tertiary hospital where both modalities are available, and in which the prescription of both continuous and intermittent techniques depends on the Nephrology Department.

The objective of our study was to describe the characteristics of patients who received SLED-type renal replacement therapy in intensive care units due to a non-standardised indication by the Nephrology specialist. As secondary objectives, we proposed to assess complications in relation to haemodynamic tolerance and electrolytes abnormalities.

A retrospective study was therefore conducted using the registry of patients in intensive care units treated with SLED between 2014 and 2016, including those who received it as the first therapeutic option, immediately after receiving CRRT or after IHD. The technique included a QB 100–150ml/min, QD 200–250ml/min and a dialysis time of 7–8h. The presence of haemodynamic instability in a session was defined as the need to start or increase vasoactive drugs during the session according to the nursing record, a fall in systolic blood pressure <90mmHg when values were greater than 90mmHg at the start of the session or a decrease of >25% in systolic or diastolic blood pressure during the session. Mortality was defined as deaths which occurred during hospital admission.

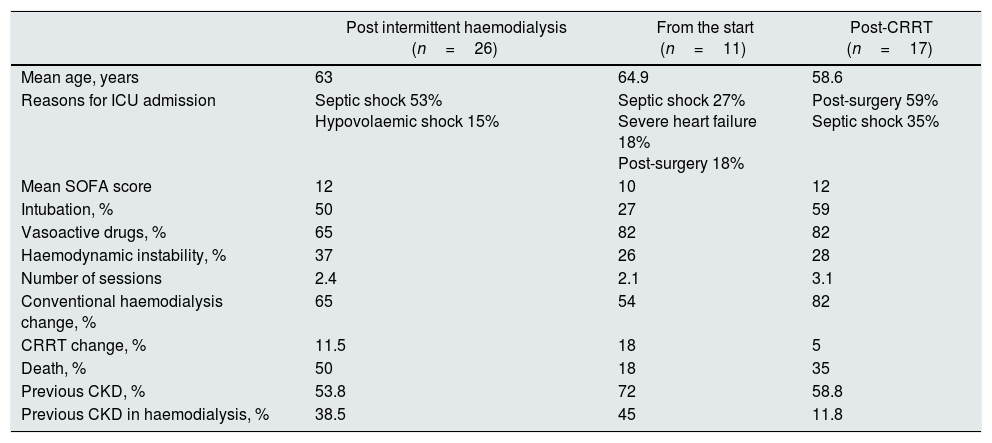

A total of 54 patients were analysed, of which 26 received the technique after IHD, 11 as the first therapeutic option and 17 as a first option after CRRT. The characteristics of the three groups, and the complications, are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of patients treated with sustained low-efficiency dialysis distributed according to the time it was performed.

| Post intermittent haemodialysis (n=26) | From the start (n=11) | Post-CRRT (n=17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 63 | 64.9 | 58.6 |

| Reasons for ICU admission | Septic shock 53% Hypovolaemic shock 15% | Septic shock 27% Severe heart failure 18% Post-surgery 18% | Post-surgery 59% Septic shock 35% |

| Mean SOFA score | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| Intubation, % | 50 | 27 | 59 |

| Vasoactive drugs, % | 65 | 82 | 82 |

| Haemodynamic instability, % | 37 | 26 | 28 |

| Number of sessions | 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| Conventional haemodialysis change, % | 65 | 54 | 82 |

| CRRT change, % | 11.5 | 18 | 5 |

| Death, % | 50 | 18 | 35 |

| Previous CKD, % | 53.8 | 72 | 58.8 |

| Previous CKD in haemodialysis, % | 38.5 | 45 | 11.8 |

In the first column, after conventional intermittent haemodialysis, in the second, as the first therapeutic option, and, in the third, as the first option after CRRT.

In addition to those related to haemodynamic tolerance, other complications that should be highlighted include hypokalemia related to the session, which was detected in 29.6% of cases. Severe hypoglycemia, chest pain and bleeding were also reported. In one isolated case, all of the above complications were reported.

Regarding the recovery of kidney function, excluding patients who received dialysis as chronic treatment or those who died during admission (n=21), 66.6% recovered full kidney function and 19% required haemodialysis upon discharge. Of the total number of patients, 29% did not require IHD after SLED sessions.

Therefore, according to our registry, the majority of treatments with SLED are indicated after poorly-tolerated IHD; secondly, as a step between CRRT and IHD, and, less frequently, as first-line treatment in critically ill patients. The patients are usually on vasoactive drugs, most of them intubated when using the technique after CRRT. Regarding haemodynamic tolerance, more than 70% of the sessions were well tolerated, with the rate falling to 63% when performed after IHD, although none of the sessions had to be discontinued due to poor haemodynamic tolerance. An interesting point is that among all patients in whom SLED was indicated after poorly-tolerated IHD, only 11.5% subsequently received CRRT, which seems to indicate that the technique has fulfilled its objective of maintaining the intermittent modality.

We therefore believe that SLED is an intermittent renal replacement technique which is not widely used as a first treatment modality in intensive care units and is more frequently used as an intermediate step between CRRT and IHD. One of the possible reasons for its limited use as a first therapeutic option is the availability of the technique due to its long duration,5 as it depends on dialysis nursing staff for its application. We believe that if knowledge of this technique is expanded, it may have an important role as it is well tolerated in critically ill patients.

Please cite this article as: Molina-Andújar A, Blasco M, Poch E. Papel de la diálisis sostenida de baja eficiencia en las unidades de cuidados intensivos. Nefrologia. 2019;39:98–99.