Dear Editor,

The elderly represent 17% of the population and 70% of drug expenditure. Adverse drug events account for between 7.2 and 14% of hospital admissions for these patients in internal medicine in Spain.1 Over the last decades this consumption has increased from 3 to 4-8.2 drugs/day,2 and it has been shown that the quantity of drugs ingested is related to adverse effects. The prevalence of hidden kidney disease in old age, and internal changes in patients due to the pathology of multiple medication has led to an increase in iatrogenic events. The following case of digitalis intoxication is submitted as an example of this.

An 82-year old woman with a history of heart failure episodes, with a previous serum Cr reference of 1.2mg/dL, arrived at an emergency ward in a mentally confused state. Multiply medicated, with an unknown dose of digoxin, plus diuretics, anticoagulants, etc., and no access to medical attention in the previous 4 months. On examination there were signs of moderate dehydration, psychomotor agitation, with a blood pressure of 120/60mmHg and a heart rate of 34 beats/min. At the emergency unit, biochemistry values were: Hct 42%, Hb 11g/dl, urea 199, Cr 4.8, K 6.8, digoxinaemia 5.4, pH 7.29, HCO 18. Chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasound and CT head scans were unremarkable. ECG: nodal rhythm of 34 per minute. She was given emergency haemodialysis without ultrafiltration, controlling the hyperkalaemia without any changes in the ECG. She was not considered in need for admission to the intensive care unit, nor were any other measures taken, such as insertion of a pacemaker or administration of digoxin antibody. For 48 hours the cardiovascular and neurological status of the patient remained unchanged, with subsequent resolution of the whole process after rehydration, digoxin levels normalised, with recovery of urine output and mental state.

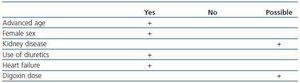

This case had several risk factors that increased the risk of drug and digoxin intoxication (Table 1), with the drug being responsible for the symptoms.

In order to evaluate kidney function when administering this drug in the elderly, more factors than the serum creatinine values should be taken into account.3 It is likely that this patient had hidden kidney disease. Our obligation as nephrologists is to carry out emergency dialysis, due to the presence of oliguric acute kidney injury after a pump failure with hyperkalaemia, obviously, not to decrease digoxin levels. The final outcome was satisfactory without any more aggressive measures being taken due to the history and age of the patient.

Digitalis toxicity is present in 0.4% of hospital admissions, with a toxicity of 10-18% in old peoples’ homes, leading to a 34% morbidity and mortality of 1%. This toxicity may be chronic, sometimes accidental and also due to attempted suicide.4 Situations (e.g. kidney disease) or drugs that increase their levels (verapamil and amiodarone, among others) can lead to intoxication. Moreover, as is known, hyperkalaemia, acidosis and hypercalcaemia enhance the effect.

Apart from the known clinical condition, hyperkalaemia requires a special mention as a prognostic factor and indicator of treatment. This may result in not only decreased excretion due to kidney disease, but a dysfunction of the Na-K-ATPase due to the digitalis effect. This would be a first order prognostic marker because it faithfully reflects the magnitude of the deleterious effect, and it is an indication for treatment with digoxin antibody (K > 5mEq/dL). Intravenous calcium administration to correct the electrocardiographic effect mediated by hyperkalaemia must be avoided, due to the risk of further increasing intracellular calcium linked to digitalis toxicity.

In another sense, arrhythmia therapy indications, among others, should be addressed by the relevant specialty, and we must practically confine ourselves to the repeated administration of atropine, if necessary, as there is a parasympathetic hyperactivity that can influence the placement of pacemakers, performing gastric lavage, etc. The use of digoxin antibodies seems far more efficient and faster, although in kidney disease a rebound effect may occur after initial administration.5

Table 1. Compliance of risk factors of digitalis toxicity in kidney function before and after treatment