We are in the midst of an upsurge in information about genetic variants associated with hereditary diseases thanks to mass sequencing and reduced costs. Being a carrier of a variant may not have pathological implications, and linking the changes found in the genome to clinical symptoms continues to be essential. We present a case that provides good proof of this.

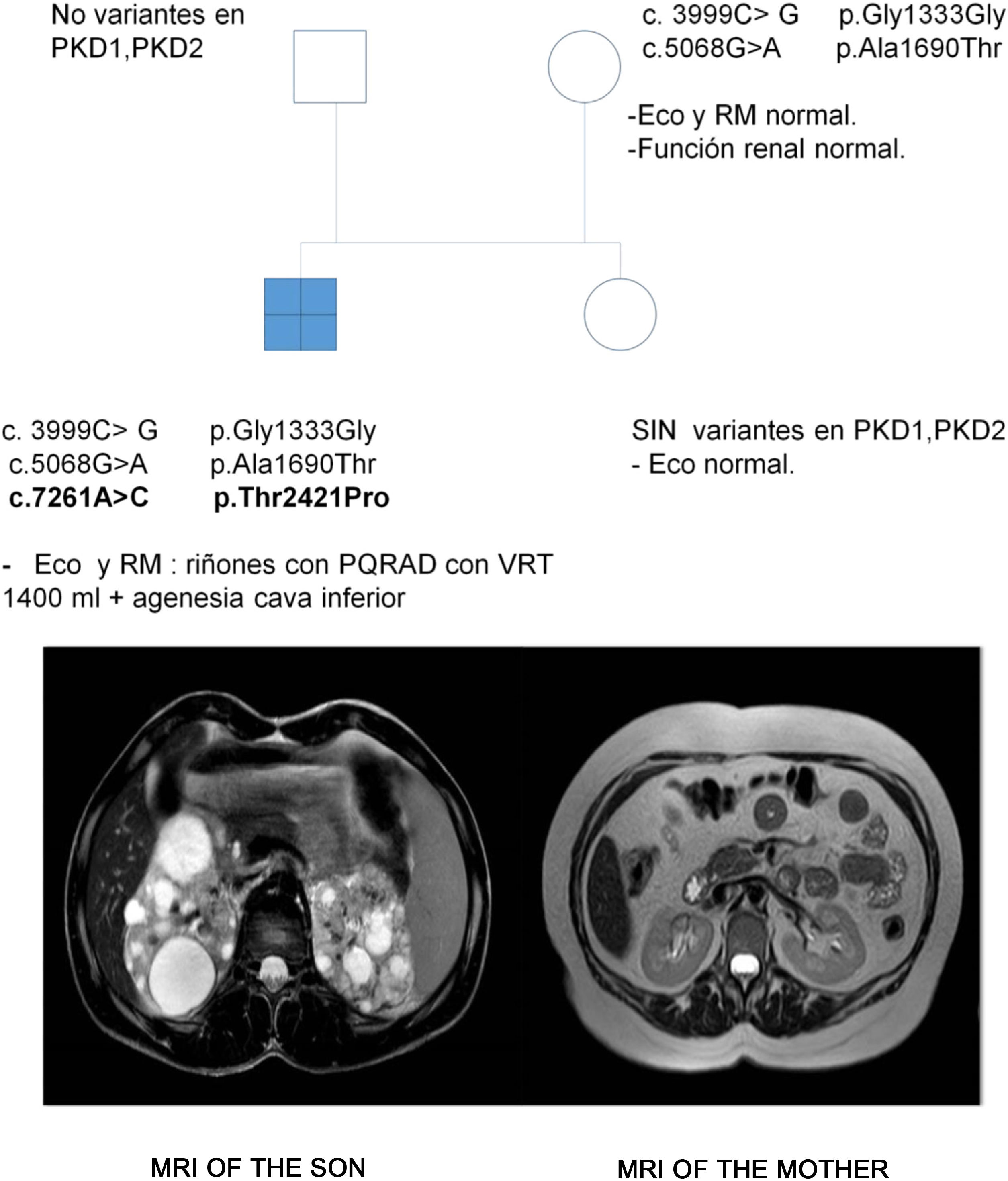

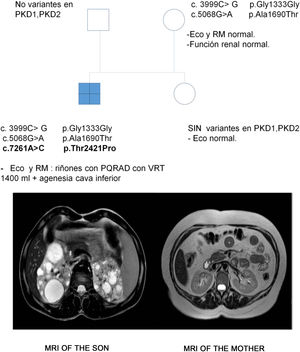

The case in question involved a 47-year-old woman referred to the Nephrology Service by Primary Care physician for follow-up of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Her 17-year-old son was incidentally diagnosed with ADPKD according to the criteria of Pei et al.1 in the context of abdominal pain. A genetic study was performed in the son to confirm the diagnosis due to the absence of a family background of the disease and the existence of normal ultrasound studies in all first-degree relatives. Three heterozygous variants were identified in the PKD1 gene, hitherto undescribed and which were classified as being of uncertain significance. However, the in silico analyses rated them as pathogenic (Table 1). The patient was symptom-free, BP 110/60 mmHg, serum creatinine 0.68 mg/dL, with no urinary alterations and the kidney ultrasound was completely normal. A genetic study was performed, identifying the heterozygous variants c.3999C > G and c.5068 G > A in the PKD1 gene, previously identified in her son. In view of this situation, a new kidney ultrasound was performed, which again presented no pathological findings, whereby an abdominal resonance was performed in which neither was any abnormality found (Fig. 1).

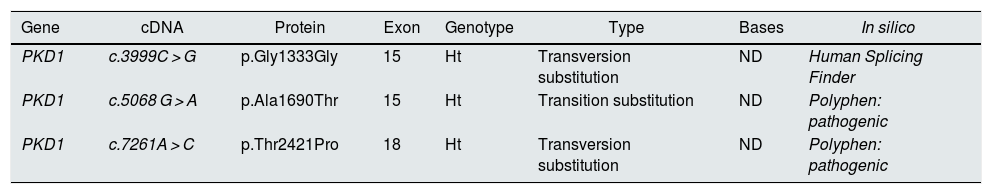

Variants identified in the PKD1 gene in the son.

| Gene | cDNA | Protein | Exon | Genotype | Type | Bases | In silico |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKD1 | c.3999C > G | p.Gly1333Gly | 15 | Ht | Transversion substitution | ND | Human Splicing Finder |

| PKD1 | c.5068 G > A | p.Ala1690Thr | 15 | Ht | Transition substitution | ND | Polyphen: pathogenic |

| PKD1 | c.7261A > C | p.Thr2421Pro | 18 | Ht | Transversion substitution | ND | Polyphen: pathogenic |

Ht: heterozygosis; ND: not described.

Genetic studies were conducted on the father and sister of the index case in the context of a segregation study and no variant was identified (Fig. 1).

The son inherited both variants in the PKD1 gene through his mother and presented another one (c.7261A > C), suspected as possibly de novo. This variant has not been described and produces, at protein level, changing a threonine for a proline in position 2421, and the in silico analysis assigned a pathogenic nature to it.

Despite the advances in genetics, ADPKD is still diagnosed clinically at this point in time. Genetic studies make it possible to explain diagnoses, although in some cases they may lead to confusion. The interpretation of genetic studies is by no means simple and requires training. Clinicians will have to become increasingly more familiar with the specific nomenclature of these studies and with searching for variants in the international databases set up for sharing knowledge about these variants. Genetics cannot be separated from clinical practice and from the study of families, because this could lead to an unsuitable appraisal of the results, as exemplified by this clinical case. The limitations of genetic studies and what may be expected of them should be explained in consultations. Being a carrier of one or several genetic variants in a specific gene is not synonymous with disease. Moreover, ADPKD is characterised by major intrafamilial variability, whereby, and even if the genetic variant is shared, a disease may evolve very differently between different individuals due to mechanisms as yet unknown.2,3 However, despite these limitations, until now, genetic studies play a major clinical role in the management of ADPKD and are essential in being able to make an early diagnosis of the disease. There is still a certain degree of controversy as to what the most adequate time for screening the children of affected patients is, since there is still no curative treatment, although neither is there any doubt that patients who carry hereditary diseases are entitled to a proper genetic assessment.4,5 The autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (GEEPAD) study group has demonstrated that in 60% of cases ADPKD is diagnosed at a mean age of 34 years and after the birth of the first child.6

The only way to make an early diagnosis of ADPKD is to classify all families properly and perform genetic studies. Building family trees, conducting sequential genetic and segregation studies, when necessary, must also be addressed by nephrologists. Changing from an individual to a familial approach is essential to the proper management of this and other hereditary kidney diseases.

This clinical case highlights the need to combine clinical experience and genetics. This challenge will enjoy increasingly greater presence in daily healthcare work and is a change that we must adapt to.