Cinacalcet has proved effective to control secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients on haemodialysis (HD). Some studies have reported an appropriate secondary hyperparathyroidism control and a better compliance after intradialytic use of calcimimetics.

ObjectivesTo assess the effect of post-dialysis calcimimetics use on mineral bone disorders and calcimimetics gastrointestinal tolerability in our HD unit.

Material and methodsA 12-week single-centre prospective study in HD patients treated with cinacalcet (>2 months). Two study periods: usual outpatient use (Stage 1) and use after HD session (Stage 2). Endpoints: (1) biochemical MBD data; (2) Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) for gastrointestinal tolerability, and visual analogic scale (VAS) for satisfaction; (3) adherence: Morisky–Green test (MG) and final tablet count (TC).

ResultsSixty-two HD patients. Fourteen received cinacalcet (22.5%). TEN patients were included, mean age was 60.9 years; patients had received HD for 80.9 months. Mean Charlson index: 9. Biochemical data: Stage 1 (initial vs. final): Ca 8.8±0.5mg/dl vs. 9.1±0.7mg/dl (P<0.05); P 5.2±0.8mg/dl vs. 4.5±1.6mg/dl, iPTH 360.3±232.7pg/ml vs. 349±122pg/ml. MG: 70%. Stage 2 (initial vs. final): Ca 9.1±0.7mg/dl vs. 8.8±0.6mg/dl; P 4.5±1.6mg/dl vs. 4.6±1.3mg/dl, iPTH 360.3±232.7pg/ml vs. 349±122pg/ml. TC: 89%. GSRS and VAS were better in Stage 2 (GSRS 7.5±5.2 vs. 4.3±1.9; VAS 4.8±2.3 vs. 6.9±2.8). No significant changes were observed in calcimimetic dose (201mg/week vs. 207mg/week), number of phosphate binders (9pts/day vs. 8.2pts/day), native vitamin D (70% vs. 60%), selective vit D receptor activators (30%), or suitable dialysis parameters.

ConclusionsPost-dialysis use of calcimimetic was effective in secondary hyperparathyroidism control, improved gastrointestinal tolerability and ameliorated patients’ satisfaction. Based on our findings, post-dialysis use of calcimimetics should be considered in selected patients with low therapeutic compliance.

Cinacalcet resulta efectivo en el control del hiperparatiroidismo secundario de los pacientes en hemodiálisis (HD). Algunos estudios han reportado un buen control del hiperparatiroidismo secundario y un mejor cumplimiento terapéutico tras la administración de calcimiméticos intradiálisis.

ObjetivosAnalizar el efecto de la administración de calcimiméticos posdiálisis sobre el metabolismo óseo mineral y la tolerancia gastrointestinal en nuestra unidad de HD.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo unicéntrico de 12 semanas de duración en pacientes en HD tratados con cinacalcet (> 2 meses). Dos períodos de estudio (6 semanas): Administración habitual ambulatoria (fase 1) y posthemodiálisis (fase 2). Datos analizados: 1.- Datos bioquímicos metabolismo óseo mineral. 2.-Test síntomas gastrointestinales (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale [GSRS]) y grado de satisfacción (escala visual analógica [EVA]). 3.-Adherencia: Test de Morisky-Green (MG) y recuento final comprimidos (RC).

ResultadosSesenta y dos pacientes en HD. Catorce recibían cinacalcet (22,5%). Diez pacientes incluidos, edad media 60,9 años y 80,9 meses en HD. Charlson medio: 9. Datos bioquímicos: fase 1 (inicio vs. fin): Ca 8,8±0,5 vs. 9,1±0,7 mg/dl (p<0,05); fósforo 5,2±0,8 vs. 4,5±1,6 mg/dl, PTHi 353±129 vs. 360±232 pg/ml. Adherencia (MG): 70%. Fase 2 (inicio vs. fin): Ca 9,1±0,7 vs. 8,8±0,6 mg/dl; fósforo 4,5±1,6 vs. 4,6±1,3 mg/dl; PTHi 3603±2327 vs. 349±122 pg/ml. Adherencia (RC): 89%. Con relación al GSRS y el grado de satisfacción, fueron mejores en la fase 2 (GSRS 7,5±5,2 vs. 4,3±1,9; EVA 4,8±2,3 vs. 6,9±2,8). No se objetivaron cambios significativos en la dosis de calcimiméticos (201 vs. 207 mg/sem), número captores fósforo (9 vs. 8,2 pac/día), vitamina D nativa (70 vs. 60%) o activadores selectivos receptor vitD (30%), ni en los parámetros de adecuación dialítica.

ConclusionesLa administración de calcimiméticos post diálisis permitió controlar el hiperparatiroidismo secundario de forma eficaz, mejorando la sintomatología gastrointestinal y el grado de satisfacción. Se debe considerar la administración de calcimiméticos post diálisis en aquellos pacientes con escaso cumplimiento terapéutico.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important public health problem, due to its high prevalence as well as its significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and socioeconomic cost.1,2

The prevalence of CKD is around 10% in the general population, and it is higher in those older than 64 years. Around 1–1.5% require renal replacement therapy, in most cases with haemodialysis (HD).3–5

The aims of treatment are directed at reducing and treating the complications associated with CKD such as anaemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism. Strong association has been shown between these disturbances and an increased rate of cardiovascular events and pathological fractures.6–9

Hypocalcaemia, vitamin D (calcitriol) deficiency, and build-up of phosphorus levels in patients with CKD are some of the multiple factors that stimulate synthesis of parathyroid hormone (PTH), leading to proliferation of the parathyroid glands and various bone and systemic abnormalities. Currently, there is a broad range of drugs to control this pathological process, including phosphate binders, native vitamin D, vitamin D-receptor-selective analogues, and calcimimetics.10–12

The mechanism of action of calcimimetics is to increase the sensitivity of the calcium-sensing receptor that is located on the surface of the chief cells of the parathyroid glands, thus reducing serum concentration of PTH, calcium, and phosphorus.13–15

The use of calcimimetics is indicated in cases of uncontrolled secondary hyperparathyroidism in which optimum levels of PTH are not achieved despite administration of phosphate binders or vitamin D. Calcimimetics have a high cost, are given orally, and are dispensed from hospital, therefore patients must periodically attend to collect the drug from their reference hospital. The main adverse effects are gastrointestinal, principally in the form of nausea and vomiting associated with high doses used for control of hyperparathyroidism.16–18

Bearing in mind the characteristics of patients with CKD on HD and all the details associated with the administration of calcimimetics, it is not difficult to understand that there is poor treatment adherence and difficult control of hyperparathyroidism, with its associated consequences.

There are few, very limited, previous studies available in the literature that have analysed the effectiveness of supervised, intradialytic administration of calcimimetics. Those studies obtained results of good control of secondary hyperparathyroidism without significant adverse effects, as well as better treatment adherence.19–21

This study aims to assess the effect of supervised post-dialysis administration of calcimimetics in our HD unit on control of abnormal bone mineral metabolism and gastrointestinal tolerance, our intention is the achievement of better treatment adherence with less side effects.

Materials and methodsThis was a prospective single-centre observational study of 12 weeks’ duration in patients on a HD programme in our centre, carried out between November 2012 and February 2013. It was approved by the ethics committee and performed in accordance with the standards of the declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria were being on a HD programme in our unit for at least 2 months prior to enrolment, receiving treatment with calcimimetics at least 2 months prior to enrolment, and giving informed consent. The exclusion criteria were sustained hypocalcaemia (<8.8mg/dL) after correcting for serum albumin, or not giving informed consent.

There were two study phases, of 6 weeks’ duration each. In the first phase (phase 1), the enrolled patients received treatment with a calcimimetic prescribed according to routine clinical practice (to be taken daily as an outpatient), which was collected by the patient at the pharmacy service in our hospital. In the second phase (phase 2), the calcimimetic was given at the end of each HD session (3 times per week) under nurse supervision, with no changes to the total dose prescribed in phase 1, and no need to attend the hospital pharmacy. The calcimimetic tablets used were 30 and 60mg. All prescribed tablets were kept and stored by HD nursing staff. The daily doses for 1 one week were added to get the weekly dose (mg/week), which was then divided in 3 for administration at the end of the HD session, aiming to give the fewest tablets possible. For example, if the dose to be given was 210mg/week (30mg/day), it was divided in the following way: first day, 60mg (1 tablet); second day, 60mg (1 tablet); and third day, 90mg (1 tablet of 60mg and 1 tablet of 30mg). The highest dose was always given on the last day of HD.

The main demographic and biochemical variables related to bone mineral metabolism were collected, as were variables regarding adequacy and characteristics of HD at the start and end of each phase of the study, coinciding with the routine scheduled follow-up tests for HD patients.

Regarding treatment with calcimimetics, information was collected on the weekly dose (mg/week), the usual time of administration, and the length of time on treatment (months). Information was also collected on the number of tablets and types of phosphate binders (calcium binders, non-calcium binders, aluminium hydroxide), vitamin D receptor-selective analogues, and native vitamin D.

In the third week of each phase, we evaluated gastrointestinal tolerance and level of satisfaction. For gastrointestinal tolerance, the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) was used as an assessment tool. This scale contains 15 items divided into 5 groups with different gastrointestinal symptoms. The 5 groups of symptoms are reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, indigestion, and constipation. It contains a Likert-type scale of 7 marks, with 1 being the post positive option and 7 being the most negative option. For assessment of the level of satisfaction, a visual analogue scale was used, with scores and visual representation between 0 (least satisfied) and 10 (most satisfied).

Treatment adherence was evaluated at the start of phase 1 using the Morinsky-Green test. This is an indirect method of evaluating treatment adherence using a self-questionnaire of 4 questions. It evaluates if the patient adopts a correct attitude regarding treatment. To be considered good adherence, the response to all questions must be adequate. At the end of phase 2, treatment adherence was evaluated by counting the number of tablets administered.

Statistical analysis was performed using the programme SPSS version 180 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as percentage. The comparison of quantitative data was done using Wilcoxon test for nonparametric related variables, and the comparison of qualitative data was done using McNemar test. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

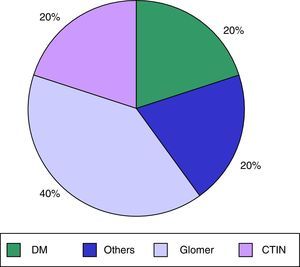

ResultsWe analysed 62 patients on a HD programme in our HD unit, of whom 14 (22.5%) were receiving treatment with calcimimetics (cinacalcet); 10 patients were enrolled and 4 patients were excluded (1 due to a psychiatric disorder and 3 due to time on treatment being <2 months). 40% were men, and the mean age was 60.9±14.1 years. Mean time on HD was 80.9±114.9 months. The main cause of CKD in our patients was diabetes mellitus, in 40%; the other causes are shown in Fig. 1. The mean Charlson comorbidity index score was 9±4.2. The mean cinacalcet dose was 201±155mg/week and the mean duration of previous cinacalcet use was 23.7±20.5 months. None of our patients had known previous gastrointestinal disease.

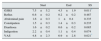

The main biochemical data on bone mineral metabolism are shown in Table 1.

Main biochemical data on bone mineral metabolism. Phase 1 and phase 2 of the study.

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | SS | Start | End | SS | |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 8.8±0.5 | 9.1±0.7 | 0.045* | 9.1±0.7 | 8.8±0.6 | 0.049* |

| P (mg/dL) | 5.2±0.8 | 4.5±1.6 | 0.270 | 4.5±1.6 | 4.6±1.3 | 0.766 |

| Ca×P (mg/dL)2 | 45.7±0.4 | 40.9±11.2 | 0.652 | 40.9±11.2 | 40.48±7.81 | 0.983 |

| iPTH (pg/mL) | 353±129 | 360±232 | 0.929 | 360±232 | 350±122 | 0.880 |

Ca, calcium; Ca±P, calcium–phosphorus product; P, phosphorus; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; SS, statistical significance.

In phase 1, serum calcium increased significantly (start vs. end: Ca 8.8±0.5mg/dL vs. 9.1±0.7mg/dL, P=.045). There were no relevant changes in phosphorus values (P 5.2±0.8mg/dL vs. 4.5±1.6mg/dL, P=.270) or intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH 353±129pg/mL vs. 360±232pg/mL, P=.929). In phase 2, serum calcium decreased significantly (start vs. end: Ca 9.1±0.7mg/dL vs. 8.8±0.6mg/dL, P=.049). As with the first phase, there were no relevant changes in phosphorus values (P 4.5±1.6mg/dL vs. 4.6±1.3mg/dL, P=.766) or intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH 360.3±232.7pg/mL vs. 349±122pg/mL, P=.880). Likewise, there were no relevant changes in the values of serum albumin (39±4.9mg/dL vs. 38.4±3.85mg/dL, P=.678), serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP 151.2±148.8mg/dL vs. 155.3±162mg/dL, P=.515), magnesium (Mg 2.44±0.52mg/dL vs. 2.44±0.54mg/dL, P=.472), or native vitamin D (36.49±19.26ng/mL vs. 37.22±10.44ng/mL, P=.861) throughout the study.

In both phases there were no significant changes in the mean total dose of cinacalcet (201±155mg/week vs. 207±151mg/week; P=0.816), or in the number of phosphate binders (9binders/patient/day vs. 8.2binders/patient/day, P=.678) or type of phosphate binders (85% calcium binders, 40% non-calcium binders, 15% aluminium, in both phases respectively), or in the percentage use of native vitamin D (70% vs. 60%) or selective vitamin D analogues (30% in both phases). There were no differences in the parameters of dialysis adequacy (Daugirdas second gen Kt/V: 1.69±0.26 vs. 1.71±0.27, P=.649) or in the HD characteristics (calcium bath: 2.5mEq/L, 20%; 3mEq/L, 50%; and 3.5mEq/L, 30% in both phases).

Gastrointestinal tolerance and level of satisfactionSeverity of gastrointestinal symptoms improved significantly in patients treated with supervised cinacalcet at the end of the HD session (phase 1 vs. phase 2 GSRS, 7.5±5.2 vs. 4.3±1.9, P=.011). In the analysis of the different aspects of GSRS, there was a lower scoring in all aspects, fundamentally due to lack of diarrhoea and indigestion, though it was not statistically significant (Table 2). There were no changes in consumption of antacid medications or gastric protectors throughout the study (90% in both phases). All patients completed the study.

Evaluation of gastrointestinal symptoms (GSRS) and level of satisfaction (VAS).

| Start | End | SS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSRS | 7.5±5.2 | 4.3±1.9 | 0.011* |

| Reflux | 0.6±0.2 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.487 |

| Abdominal pain | 1.6±0.3 | 1±0.4 | 0.335 |

| Constipation | 1.5±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | 0.235 |

| Diarrhoea | 1.6±0.2 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.085 |

| Indigestion | 2.2±0.4 | 1.1±0.4 | 0.074 |

| VAS | 4.8±2.3 | 6.9±2.8 | 0.021* |

GSRS, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale; SS, statistical significance; VAS, visual analogue scale. Average score (1–5) of symptoms according to the different categories. Start vs. end: GSRS categories: reflux, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhoea, and indigestion.

There was also a higher scoring for level of satisfaction, using the visual scale (4.8±2.3 vs. 6.9±2.8; P=.021), in patients who received supervised cinacalcet treatment at the end of the HD session.

Treatment adherenceIn phase 1, using the Morisky–Green test, treatment adherence was 70%. In phase 2, using counting of tablets, adherence was 89% (245 tablets administered/276 prescribed).

DiscussionIn our patients, supervised intermittent administration of calcimimetics after dialysis sessions was effective in control of secondary hyperparathyroidism. In the literature, there are recent studies that have assessed the effectiveness of supervised intradialytic administration of calcimimetics, with results of good control of secondary hyperparathyroidism without significant adverse effects, and better treatment adherence.

Al Hilali et al.19 saw a similar effect in PTH suppression after administration of calcimimetics twice per week after dialysis, compared with a daily regimen, in a group of 27 patients on a HD programme. Likewise, Haq and Chaaban20,21 observed that post-dialysis administration of cinacalcet was as effective as the standard daily home schedule in a group of 11 patients, after 16 weeks of follow-up. In contrast to the aforementioned studies, our study did not have a comparison group, there were no changes to the treatments involved in hyperparathyroidism control or in the dialysis characteristics, and also, our patients had previously received treatment with calcimimetics. Although it is true that with a higher treatment compliance there would be an expected improvement in values of bone mineral metabolism control (above all calcaemia and iPTH), in our study we saw statistically significant changes only in serum calcium values in the different phases, with no changes in the values of phosphorus and iPTH. Regarding the difference in serum Ca, this could have been due to incomplete taking of calcimimetics in phase 1, and correct treatment compliance with calcimimetics in phase 2. The absence of significant changes in iPTH values could be attributed in part to use of one isolated value and not average values of iPHT, as well as the great variability in average values in a small sample that is analysed with a nonparametric test. However, in both study phases, our patients remained within the therapeutic targets of the guidelines on bone mineral metabolism from various nephrology societies, without changes in the total doses administered. Therefore, we interpret that the 2 patterns of administration are equally effective in the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Many medications have adverse effects that can contribute to their irregular consumption. The gastrointestinal side effects of calcimimetics are widely known, the most common symptoms being nausea (21–43%) and vomiting (13–30%).11,12 Taking medications at night or with food are some of the strategies used to minimise those adverse effects.22–25 In our study, gastrointestinal symptoms improved after the supervised post-dialysis administration of calcimimetics. This was fundamentally due to the symptoms of diarrhoea and indigestion, which were reduced by up to 50%. These findings were attributed to the intermittent taking of the medications, which were not taken for a total of 4 days per week, thus avoiding the gastrointestinal upset associated with a daily dose. Regarding this, the low dose prescribed in our patients (most of the patients received a regular dose no more than 60mg/day) as well as the routine intradialytic ingestion of food, could have minimised gastrointestinal symptoms. In fact, under supervised administration, our patients received higher individual doses than they had routinely been prescribed, and there were no discontinuations due to gastrointestinal intolerance during the study. Furthermore, during the supervised post-dialysis administration, the level of satisfaction improved significantly. This finding could be explained firstly by the reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms, and secondly by the simple fact that patients avoided the inconvenience of collecting medications at the hospital pharmacy in our centre, which is located away from the dialysis unit and has opening hours that do not always coincide with routine HD sessions. Following the results of our study, we will consider post-dialysis administration in patients with difficulty attending the hospital pharmacy (due to either physical condition or scheduled HD time).

As previously mentioned, patients on HD have a high drug load, due to their associated increased concomitant conditions, which can result in poor treatment adherence. The average rate of treatment compliance in randomised controlled studies in patients with CKD on a HD programme is around 42–78% and is getting lower over time.26–30 In our study, the adherence rate is similar to that previously published. As expected, with supervised post-dialysis administration, treatment compliance improved, despite the use of different methods of evaluating treatment compliance in the different phases of the study. The Morisky–Green test is widely used in various population studies of therapeutic inertia and compliance, particularly in the setting of the hypertensive population. It was used in phase 1 to maintain neutrality, to avoid factors of confusion and subsequent interpretation (for example, encouraging the taking of medications in supposedly noncompliant patients). In phase 2, in order to be objective, it was decided to use the final count of cinacalcet tablets to calculate the total quantity and number of tablets of medication used. However, despite supervision by a nurse, treatment nonadherence was 11%. This fact could be attributable to an oversight of the nursing staff in administering the medication in the final moments of disconnecting the patients, when there are other care tasks to be done; or possible errors in the number of tablets to administer after the HD session (for example 2 tablets instead of 3). Perhaps using a single administration schedule, or taking the medication at another point in the HD session could minimise this mild nonadherence, although the end of the HD session was chosen to ensure the same moment for taking the medication for all patients in phase 2 and to avoid errors in assessment of gastrointestinal symptoms (because of intradialytic food), as well as to not coincide with the administration of other regular medications by nursing staff during HD sessions.

One point to highlight in our study is that it was carried out according to routine clinical practice. That is to say that in current practice, despite the medical indications, it is not uncommon to give low doses of calcimimetics on alternate days, thanks to recent improvements in the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Among the multiple limitations of our study, some of which have already been mentioned, the most notable were the low number of patients, requiring the use of a non-parametric statistical test, and the short follow-up time in our patients; though a period of 12 weeks was chosen to avoid potential changes in regular medications associated with bone mineral metabolism after routine 3-monthly tests. Regrettably, it was not possible to do a cost-economic analysis. Studies with more patients and a longer duration would be needed to confirm the effectiveness and gastrointestinal tolerance of calcimimetics given under supervision post-HD, in the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism.

In conclusion, in our study, supervised post-dialysis administration of calcimimetics was effective in the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism, with fewer gastrointestinal effects and a higher level of satisfaction. Based on these results, we consider the administration of post-dialysis calcimimetics to be effective and, above all, beneficial in determined patients with poor treatment compliance.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Esteve Simo V, Moreno-Guzmán F, Martínez Calvo G, Fulquet Nicolas M, Pou Potau M, Macias-Toro J, et al. Administración de calcimiméticos posdiálisis: igual efectividad, mejor tolerancia gastrointestinal. Nefrologia. 2015;35:403–409.