Dear Editor,

Cholesterol emboli syndrome (CES) is caused by cholesterol crystal deposits in small arteries, spread throughout different organs: kidneys, brain, eyes, pancreas, intestine, skin and toes. It can occur spontaneously, however it is often observed in hypertensive, older patients who are smokers with atherosclerosis, following vascular surgery or anticoagulant treatment.1,2 It is a significant condition because of its high morbidity and mortality and because it is often underdiagnosed.3,4

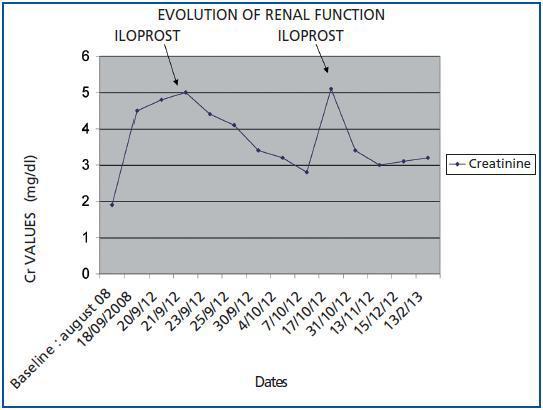

We would like to present the case of a patient with suspected clinical CES and partial recovery of kidney function (KF) following early treatment with iloprost. The changes in kidney function can be found in figure 1.

A 79-year-old male patient who was an ex-smoker and light drinker with a history of HBP and hiatus hernia, underwent surgery for a hydatid cyst in the right lung at the age of 33. He also had a history of chronic kidney disease secondary to chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy, with baseline creatinine levels of 1.8-2mg/dl. He presented ischaemic heart disease characterised by unstable angina and catheterization was carried out with the implantation of 2 stents.

In September 2008, 15 days after catheterization, the patient was admitted into the Department of Neurology because of an ACVA affecting the left posterior cerebral artery, when deteriorated renal function was detected, with maximum creatinine 5.0mg/dl and ischaemic lesions on the soles of both feet with distal cyanosis. The biochemistry showed: eosinophilia, proteinuria 0.5g/day, and all other values within the normal range. The abdominal ultrasound and renal Doppler scan were normal. No cholesterol crystals were detected upon fundoscopic eye exam.

With a suspected diagnosis of cholesterol atheroembolism because of his history of atherosclerosis and invasive vascular surgery 15 days before, we began statin and support treatment, controlling blood pressure with calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors and betablockers. Empirically, we continued to administer corticosteroids (1mg/kg weight), without obtaining a favourable response. We decided to begin treatment with iloprost, starting with a dose of 2ng/kg/min for 6 h/day, for a total of 14 days. This produced redness of the skin and headaches after the first dose was administered which decreased with the lower rate of infusion. In this way, we managed to obtain a gradual reduction in creatinine levels, which stabilised at 4mg/dl at discharge. Patient diuresis was constant throughout. The distal cyanosis improved considerably.

In October 2008 he was admitted once more for a urinary infection and signs of acute on chronic kidney disease affecting the volume-depleted patient, with creatinine 5.1mg/dl. After saline solution therapy, a tapering regimen of corticosteroids (16mg/day) and four more doses of iloprost, we were able to stabilise kidney function, recording creatinine levels of 3mg/dl.

Regular patient check ups continued in the Department of Nephrology and RF remained stable with creatinine levels 2.8-3.0mg/dl.

In March 2009, the patient died of a massive digestive haemorrhage.

CES has a very poor prognosis, with a 63% mortality rate,3 because of the impact of the cholesterol emboli on different organs. Our patient died of a digestive haemorrhage with preserved kidney function, although the majority of patients who survive require dialysis. Since no specific treatment has been established, the measures taken in the first instance were based on the prevention of triggering factors,5 and later on, on support measures to control blood pressure (ACE inhibitors, betablockers, calcium antagonists, diuretics), statins and haemodialysis if necessary.2,6 There is some controversy surrounding the beneficial effects of corticosteroid treatment and its effectiveness is subject to debate.6,7

In the case of our patient, in light of the history of atherosclerosis, HBP with heart catheterization carried out 15 days before, the episode of ACVA, deteriorated kidney function and distal cyanosis with highly suspected CES, we decided to start early treatment with iloprost given the lack of response to the support measures taken and the corticosteroids. With the new treatment we managed to improve renal function to a certain extent, since it was stabilised and dialysis treatment was not required. Similarly, the distal cyanosis lesions also made good progress.

Several articles published in the literature describe the benefits of treatment using prostacyclin analogues, iloprost, vasodilator agents and antiaggregants. These are effective in treating leg ischaemias, Raynaud¿s phenomenon in connective tissue disease, pulmonary hypertension and are currently recommended for scleroderma renal crisis. These have been used recently for treating cholesterol atheroembolisms as they quickly improve distal cyanosis, leg pain and kidney function.8-10

Figure 1.