To the Editor,

Portal hypertension (PHT) is the most common liver cirrhosis-related complication and has a high morbidity and mortality index. Measuring the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is the method of reference to estimate PHT. The objective of this study was to determine the HVPG and the necroinflammatory and fibrotic activity in liver tissue from a transjugular biopsy in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and liver disease to establish the correlation with analytical and radiological data, and determine whether a treatment prior to progression to advanced kidney disease or kidney transplant was adequate, and to assess the technique’s profitability and safety in patients with kidney failure.

PHT is defined as a pathological increase in hydrostatic pressure in the splanchnic vein territory, which causes the portal-cava gradient to increase above its normal value (1-5mm Hg).1 It is the most common liver cirrhosis-related complication and has a high morbidity and mortality index.

Measuring the HVPG is the best method for estimating PHT and can be used in prognosis, meaning that it is the test of choice to assess PHT.1-3 A HVPG of 6-9mm Hg represents a subclinical PHT, while PHT complications develop when HVPG is above 10mm Hg.4-7

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend liver biopsy in assessing kidney transplant candidates’ liver disease.8 According to the Spanish Society of Nephrology, hepatitis C (HCV) carriers can be kidney transplant candidates once their liver disease has been completely assessed.9 The transjugular approach is recommended, given the risk of bleeding due to clotting disorder and platelet dysfunction associated with uraemia and intradialysis antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatment. It allows HVPG to be measured to confirm and assess PHT without having to puncture the liver capsule and peritoneum, reducing pain and risk of bleeding.10,11 Although measuring HVPG is an invasive procedure and is not available in all hospitals, its reproducibility and low number of complications mean that it is gaining more importance.12

The METAVIR score assesses the necroinflammatory activity (grade A) and fibrosis (stage F) using a coding system of two letters and two numbers.13

The objective of this study was to determine the HVPG and METAVIR in patients with CKD and liver disease, to establish the correlation wtih analytical and radiological data, and determine the convenience of treatment previous to progression to advanced CKD or kidney transplant, as well as assessing the profitability and safety of the technique in CKD patients. This is the first study that described the relationship between HVPG and clinical data of CKD patients.

Of the 277 patients undergoing predialysis and haemodialysis in our area, 11 kidney transplant candidates with chronic liver disease were referred to the hepatology department to assess their hepatic situation before their condition progressed to advanced CKD or being included on the kidney transplant waiting list.

In accordance with our hospital’s protocol and after having received the informed consent, a transjugular liver biopsy was performed to assess the histological severity of the liver disease and to exclude concomitant causes of dysfunction. At the same time, HVPG was measured to confirm and assess PHT. Antiplatelet drugs were withdrawn 5-7 days before, depending on the severity of the ischaemic heart disease. Haemodialysis patients were examined on a dialysis-free day, having undergone heparin-free haemodialysis the day before. The liver biopsy was performed by cut and aspiration, using an 8 F catheter and scope control. For each examination, 15ml-20ml of iodine contrast was administered. For non-dialysis patients, we performed prophylaxis for contrast-induced nephropathy with saline solution and N-acetylcysteine. All patients’ histologies were assessed by one pathologist using the METAVIR score.

Analytical and radiological data were taken to clinically determine the liver disease and we monitored the haemoglobin levels and kidney function at 6 and 24 hours after the procedure.

The procedure was performed on 6 patients of the 11 that had been selected: one patient was submitted for a kidney transplant before the examination, two were excluded due to contraindications (hepatic polycystic disease , dermal fibrosis), and two turned down the examination.

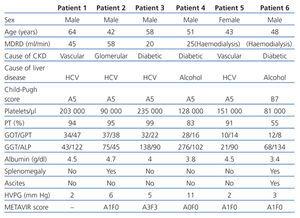

The characteristics of the patients studied are shown in Table 1.

Patient 1 presented with a normal HVPG, with no indirect signs of PHT. The patient could not undergo the transjugular liver biopsy because of the pronounced angle of the suprahepatic vein, which stopped the catheter from being placed (stiff guidewire). Patient 3 presented with a normal HVPG, with no indirect signs of PHT. METAVIR score was A3F3 with normal GOT/GPT and high GGT, without signs of alcohol consumption. Patient 5 presented with a normal HVPG, with no data for PHT. METAVIR score was A1F0 with normal transaminases. Patient 6 presented with a normal HVPG, with indirect signs of PHT (thrombocytopaenia, splenomegaly and ascites). METAVIR score was A1F0, with normal GOT/GPT and slightly high GGT.

Patient 2 had a HVPG of 6mm Hg (subclinical PHT) with PHT data (thrombocytopaenia and splenomegaly). METAVIR score was A1F0, with slightly high GOT/GPT and GGT. Patient 4 obtained a HVPG of 11mm Hg (severe PHT), without indirect PHT data. METAVIR score was A0F0, with normal GOT/GPT and high GGT, which was likely to be related with active alcohol abuse.

None of the patients suffered procedure-related complications.

This was a short study, including patients with CKD and liver disease. Measuring their PVPG and performing a liver biopsy revealed clinical data that were not found in analytical and radiological tests, and which also modified treatment for two patients.

The HVPG levels of patients 1, 3 and 5 coincided with indirect signs of PHT. Patient 2 also presented with subclinical PHT with thrombocytopaenia and splenomegaly. However, patient 4 had a HVPG of 11mm Hg which is not in accordance with indirect PHT signs (absence of thrombocytopaenia, splenomegaly and ascites), and patient 6 had a normal HVPG with thrombopaenia, splenomegaly and ascites.

Four patients’ liver histology matched the METAVIR score with cytolysis enzymes. Treatment of HCV-induced liver disease would have been ruled out for patient 3 given the level of transaminases, while the histology shows a significant necroinflammatory and fibrotic activity, which changed the therapeutic treatment.

Patient 6 had low PT, thrombocytopaenia, hypoalbuminaemia and ascites, which pointed towards a chronic decompensated liver disease. He was indicated liver and kidney transplant. However, this study found a patient with liver disease free of PHT; histology was A0F0 and liver transplant was not indicated. History of alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis could explain splenomegaly, and ascites could be of a cardiac origin, due to right heart failure and a protein count greater than 3g/dl in the peritoneal fluid. Furthermore, we were aware that there were no oesophagogastric varices, which support a HVPG of less than 10mm Hg.

CKD patients are at a high risk of suffering severe complications following percutaneous liver biopsies. A study conducted on 72 haemodialysis patients showed that 13.2% suffered complications.14 Our series only examined 6 patients, but the transjugular biopsy seems to be safer than the percutaneous method.

Our data suggest that measuring HVPG and liver biopsies are useful for correctly assessing CKD patients and liver diseases, and defining candidates for antiviral treatment and liver transplants. This means that it should be included in the liver disease examination for CKD patients.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients studied