Chronic kidney disease is associated with a wide range of stressful situations causing important physical and psychological consequences. It is not usual that psychology professionals are active members of nephrology teams. In consequence, these alterations are not properly assisted. Our aim is to present how a psychologist is integrated into a nephrology department and its preliminary results. We designed a clearly defined integration process, starting with a therapeutic communication training program for all staff members. In the model we have prioritised pre-emptive interventions in order to promote the adaptation process, which is far from simple psychological symptom control. The binomial patient family is considered the main objective for care, choosing an interdisciplinary approach. We worked more from a health psychology perspective than from a mental health perspective. During 2008, the psychologist attended to 571 patients (mean 48 patients/month). The total number of interventions was 1,022. Most cases (45.2%) were derived from the advanced chronic kidney disease program, mostly related to demands about emotional impact of commencing renal replacement therapy. Others were: suspected depressive episode, adherence, primary caregiver in an overwhelming emotional state, bereavement, anxiety and support in decision making process. This experience is a stimulus for the integral approach of the renal patient.

La insuficiencia renal es una enfermedad que genera un amplio rango de situaciones estresantes, que ocasionan trastornos tanto de tipo físico como psicológico. Es anecdótico que profesionales de la psicología sean miembros activos de los equipos de nefrología, por lo que dichas necesidades pueden no ser atendidas adecuadamente. Nos proponemos describir el proceso de incorporación de este profesional en un servicio de nefrología y presentar resultados preliminares de su actividad. El proceso se inició con un programa formativo en comunicación difícil. En el modelo elegido se prioriza el trabajo preventivo; se trata de facilitar los procesos de adaptación más allá del mero control de síntomas psicológicos; se asume como prioridad asistencial el binomio pacientefamilia y se opta por un estilo de relación sinérgica interdisciplinaria. Se trabaja más desde la perspectiva de la psicología de la salud que desde la óptica de la salud mental. A lo largo del año 2008 el número de pacientes atendidos por el psicólogo ha sido de 571 (media de 48 pacientes al mes). El número total de intervenciones fue de 1.022. La mayoría de los casos atendidos en consulta (45,2%) procedían de la consulta de enfermedad renal crónica avanzada (ERCA). Otros motivos de derivación fueron: sospecha de depresión, cumplimiento, sobrecarga del cuidador principal, duelo, ansiedad y apoyo en la toma de decisiones. Este tipo de experiencias son un estímulo para el abordaje integral del paciente con enfermedad renal.

INTRODUCTION

The Nephrology Service of La Paz University Hospital has worked regularly for more than two years with the group of psychologists from the hospital’s Haematology Service. The relationships were initiated mainly for monitoring certain complex patients and for training medical professionals and nurses in therapeutic communication tools.

On several occasions, from close contact and shared reflection, nephrology service professionals have expressed the need for additional support that, in many cases, goes above and beyond the limits of the speciality training in nephrology or certification in nursing. This has been based on the hospital’s caring for patients with various degrees of renal impairment and the fact that this disease occurs and progresses in different ways, many of them with significant complexity.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this paper is to describe the process of incorporating a psychologist into a clinical nephrology service in a tertiary hospital, with particular attention to the criteria that we believe guarantee a safe and successful integration of all parties involved. Secondly, our goal is to present a brief description of the health care activities (leaving the teaching and research activities for another publication).

The scheme that we will follow begins with the description of the assessment of service needs and then goes on to describe the process of implementation, paying particular attention to the criteria that we believe should be addressed to ensure the psychologist’s long-term effectiveness and work. Here we present the results of the first year of the psychologist’s activities and then conclude with some final thoughts regarding the use of similar processes in other medical services.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Needs Assessment

Psychological aspects of renal failure

Renal failure is a disease that produces a wide range of stressful situations in the patient and his or her environment, resulting in both physical and psychological disruptions.1 The patient with renal disease faces a loss of health that will be perceived as a threat, which manifests in high levels of emotional impact that can interfere with normal functioning. Patients with stage 4-5 advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD) have significant changes in their quality of life when compared with the normal population, and the psychological impact due to symptoms increases with decreasing glomerular filtration rate.2 Psychological disturbances are common in patients with renal diseases and may result in hospitalisation rates from 1.5 to 3.0 times higher than in other chronic diseases, which results in significant morbidity.3 Depression is the most common psychological problem in the population with advanced stage renal disease and may be effectively addressed with pharmacological and psychological interventions.4 The rate of depression in haemodialysis patients is 44% while patients with stage 5 ACKD make up a risk group due to the life stressors that they face.5

Anxiety disorders in this population have been underestimated by associating them with the depressive disorders, but they are truly significant and diagnostic procedures should probably improve in order to effectively detect them.6

The psychologist’s work is very focused on meeting patients’ needs and in tapping into their own psychological resources. In this line, as Magaz-Lago reminds us, the health psychologist will promote adaptive responses to improve compliance with medical prescriptions, better symptom management, family counselling, optimised communication with professionals, and improvements in quality of life.7 Addressing the patient with renal disease requires a holistic view of his or her health status together with both biological and psychological, social and spiritual aspects associated with the patient’s condition.8

Inter-consultations

La Paz University Hospital has a team of psychologists that is integrated into the haematology service. This team has more than 30 years of extensive clinical experience in a hospital-based medical service. In recent years, the team of haematology psychologists started to receive formal requests for support through consultations for intervention with some highly complex clinical cases involving renal patients and their families. The psychological and social complexity of these patients grew gradually day-by-day. The clinicians sought assistance. Thus, faced with needs that exceeded the abilities of medical and nursing intervention, new assistance mechanisms were created within the hospital.

Training in difficult communication and decisionmaking (counselling)

Since the demands for psychological intervention were increasing at the same time as the complexity of care in terms of their psychosocial variables, a proposal was made for formal training with the entire nephrology service within the framework of continuing education. The aim was to improve the therapeutic relationship and serve as a means of preventing burnout within the service. The course was proposed within the relational technology of counselling. For effective clinical practice in complex areas such as nephrology, good communication is essential for facilitating the therapeutic relationship and the decision-making process, all in threatening scenarios such as starting renal replacement therapy or withdrawing it. Counselling is a therapeutic tool that has proven very useful in the health field as a suitable methodology to facilitate therapeutic communication.9-11 It is an interactive process that promotes both biological and biographical health, reduces adverse emotional states, promotes self-regulation of the professional, and favours adaptation to the disease.12

The specific training content of the course was designed to provide resources to assist nephrology professionals in their respective care settings, both as crisis and chronic situations, where the communication is high in emotional intensity and has to tackle sensitive processes such as decision-making (Table 1).

Over the course of 2007, there were five sessions of a 12- hour interdisciplinary course for doctors and nurses from the service. At the beginning of each session, participants were asked to set out in writing the three most feared or most difficult situations, from the point of view of therapeutic communication and relationship. The main difficult or feared situations from the group are listed in Table 2.

Criteria and implementation process of the psychologist into the nephrology service

In reviewing the literature, we have not found any similar experiences that describe the process of integration of a psychologist, looking at criteria and process, into a medical service, either in general or in nephrology in particular. With this background, once the needs had been identified, the institutional decision was made by the chief of service to look for a psychologist with the appropriate background to work as part of the team and, simultaneously, to get external funding to support it, since the health system itself currently does not provide funds for such implementation. It is worth highlighting that, for years, the nephrology service had been formally requesting the incorporation of a psychologist into the staff from the hospital management and the response was never positive.

Criteria

A specific professional profile was sought that was focused on health psychology training and experience with teamwork, preferably in the hospital environment. In our experience, it is very important that the psychologist is fully integrated into the dynamics of the service. This defines their participation as regular and standardised in the internal activities involving practitioners (clinical sessions, organisational meetings, continuing education, research, attending conferences, etc.). The psychologist is not so much a consultant but a member of the team, which implies sharing spaces and processes.

Furthermore, it is also important that patients perceive the presence of the psychologist as an additional, stably integrated, member of the service. To do so, the psychologist’s presence was facilitated in the medical visit or on certain consultations. The perspective was clear. Faced with a consultation model, we explicitly opted for a model of integration into the service with differential and significant emphases. In the chosen model, continuous scheduled and preventive work is prioritised over intervention by consultation at times of crisis. Great care is taken to facilitate the adaptation process as a fundamental strategy that goes beyond the mere control of symptoms. The necessary care of the patient-family binary is taken to be the priority in such chronic processes. A relationship style of sustained interdisciplinary synergy is chosen, which weaves partnerships into team-building, and not through the simple, but important, multidisciplinary contribution alone. It works more from the perspective of health psychology than from the viewpoint of clinical psychology in the strict sense.

Finally, there is a clear commitment, without forgetting the psychopathological aspects, not to run away and to address the experience (great experience) of suffering of the patient with kidney problems.

As background, there is an entire anthropological approach that focuses not only on symptoms and problems, but also in the resources and abilities.13,14 Table 3 briefly outlines the differential aspects of this approach. Obviously, the model also incorporates the principles of modern bioethics (of non-maleficence, justice, beneficence, and autonomy), encouraging a kind of symmetrical, deliberative relationship,15 which forms the basis for providing care that is focused on quality and excellence. Needless to say, the research dimension continues and deepens, as it must in any clinical service in a university hospital. In a service as broad-based as that of nephrology, we decided to prioritise provision of care in some areas according to need:

ACKD patients with a high likelihood of starting dialysis. Patients facing an acute process within the chronic condition.

Patients on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis having adaptation difficulties.

Patients with serious problems with lack of compliance with treatments, which often require increased income and additional testing and the resulting increase in overhead spending and health care.

Patients at the end of life and prevention of complicated grief.

As mentioned, the dynamics of work include family intervention when indicated. In addition, other professionals in the service may use the psychologist for crisis intervention with patients who were not included in the above-mentioned areas or for more complex or problematic patients. All this is properly coordinated with the psychiatry consultation service when needed for supportive drug treatment.

Furthermore, strategies were established so as to prevent burnout,16 from ongoing training in therapeutic communication tools and the creation of interdisciplinary meetings between doctors and nursing staff to enhance the formal channels of internal communication within the service.

Process

Once the service chief’s proposal was completed, the selection process began to find the person who best fit the profile. Once the professional was selected, it was essential to design the inclusion of the psychologist into the service in order to reduce barriers and enhance opportunities. During the first month, a rotation in the different sections of the service was scheduled as a participant observer in order to discover barriers and resources for patients, family, and the healthcare team in each scenario. It was after this month that a research project was presented to the chief of service that met the most pressing needs and allowed for the development of psychological activity within a safe and adequately funded role.

This professional does not rely on the medical services that are usually part of their own discipline for reviewing clinical cases, starting a permanent shared position as health psychologist, or conducting psychological research specifically. For this, the appointed psychologist relies on technical supervision with a consultant psychologist outside of the service who is still part of the hospital. Equally important is that the organisational monitoring be performed monthly with the chief of nephrology service in order to coordinate the internal aspects of the service, status of the team (challenges and opportunities), and the development of research projects.

RESULTS

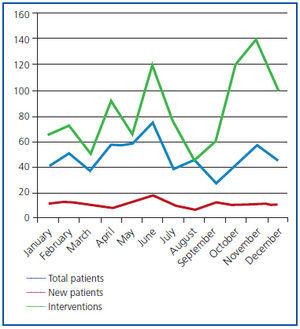

Activity during this first year has focused on the triple task of provision of care, research, and teaching, understanding that these are three interdependent axes and constantly feed back onto each other in a teaching hospital such as ours. The number of patients seen by psychology was 571 over the course of 2008 (average 48 patients per month). 1022 interventions were conducted with patients and family, an average of 85 interventions per month (Figure 1).

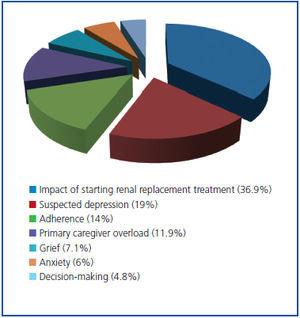

Aside from the daily interventions performed as a precautionary measure and in the usual scenarios of service (hospital rooms, ACKD consultation room, haemodialysis unit, peritoneal dialysis unit, among others), 85 cases were treated as outside psychology consultations thanks to explicit referrals made by medical and nursing staff from different sections of the service. The interventions are separated by service source and reason for referral (Figures 2 and 3).

Most cases seen in consultation (45.2%) came from ACKD consultation. Sixty-four percent were women. The mean age was 52.6 years (standard deviation [SD]: 18.393). Fifty-six percent were actively employed at the time of the intervention. Half (52.4%) were married or living with a partner.

DISCUSSION

An interesting piece of quantitative data bears mention. It has to do with the demands that were made, and especially those that were intervened upon, which are clearly consistent with the needs identified in the literature. To mention just one example, the two main reasons for referral were patients about to start a dialysis program, with the resultant practical and emotional impact on their lives and, second, patients in whom professionals sensed or suspected a possible depressive process. The reality since then has shown that it was reactive depression, usually immersed in a process of adaptation. It is well known that all these processes of adaptation coexist with the significant experience of suffering.

It is also important to note the process of implementing the psychologist into a pre-existing team with a long history. When processes are not carefully implemented, the results depend more on trial and error than on the initially goals of the participants. The following are some key points:

1. The professionals who designed the process also discussed in depth the barriers and opportunities, thus allowing for anticipation of any resistance and tapping into the full potential available. For example, it was very useful to begin by defining what we did not want to happen. Namely, that the psychologist was isolated, that other service professionals were not involved in the emotional support of having a psychologist on board, that expectations were unrealistic and disproportionate, which would generate later frustration. Raising all of these possible issues facilitated the prevention of such difficulties.

2. The process has been clearly participatory and transparent. Some professionals have participated in the design, others in the gradual introduction of the psychologist, and everyone in offering a welcoming attitude to the new person. Real and not just perfunctory participation reduces initial resistance and serves to clarify expectations.

3. Monitored process. Things are not generated solely from desire or only from design. The best-designed engines do not work if not oiled or appropriately maintained. Monitoring requires defined and systematic time and space.

Throughout the process, the psychologist has conducted monthly monitoring meetings with the nephrology service chief and with the outside adjunct psychologist, who is part of the hospital. We took advantage by monitoring the implementation process and the technical supervision of work already performed or yet-to-be performed.

We believe that this experience can be replicated. Obviously, not in exactly the same way because no two scenarios, no matter how similar they may be, have the same institutional cultures. However, we do understand that the process and context keys, as well as the criteria, can be enormously helpful for knowing how and where to proceed. The great achievement of this experience is to say that it is possible and it is also useful, both for professionals and, above all, for patients and families.

A priori, this model of integration may also have some important limitations. Firstly, clear leadership is needed not only to create a sense of belonging and usefulness for the psychologist, but also in the need to invest energy in the process, especially at the beginning. Without commitment and leadership it is highly unlikely that the goals would be met. Secondly, we do not know how it would have been received if the psychologist had arrived more formally as an adjunct to the service (consulting psychologist). At least from a theoretical standpoint, it is possible that someone would have seen it as a missed opportunity to include a different consultant (a physician) to ease the workload.

As for future prospects, undertakings like this one prompt us to consider how to continue developing strategies such that the psychologist might reinforce in the team the evaluation and treatment of psychological needs of the patient with renal disease. It may also prompt the development of proactive strategies in other hospital services, so they do not have to wait for the system to react positively (which is very unlikely) to these needs, thus we must not forget that treatment of suffering is not really on the menu of the system’s services. Finally, these considerations also drive us to be rigorous in the collection of treatment data, which in the future may help sustain a commitment such as that currently being done in the nephrology service.

Such experiences are an encouragement for real and proven belief in the multidimensionality of the individual, in the plurality of approaches, in teamwork, and in the enormous wealth generated by bringing people together to cooperate and not to compete. In short, it is a benefit for patients and highly satisfying for professionals.

Acknowledgements

To Drs. Cristina Coca, Laura Díaz Sayas, Carola del Rincón and Teresa López-Fando. This project would not have been possible without their clinical and teaching abilities. To all the physicians and nursing staff of the Nephrology Service of the La Paz University Hospital for their hospitality and their capacity for dialogue. To Shire for giving continuity to this project with a non-restrictive grant.

Table 1. Content of the counselling course in the nephrology service

Table 2. Common difficult or feared situations in daily practice

Table 3. Axes of proposal: Decalogue of the integration model

Figure 1. Psychologist¿s activities during 2008.

Figure 2. External consultations to the psychologist: classification by referral source.

Figure 3. Consultations to the psychologist: classification by problem found.