Introducción: Existe evidencia creciente del papel del ácido úrico (AU) como factor de riesgo cardiovascular y renal. En este trabajo analizamos la asociación entre niveles basales de AU y mortalidad global en una cohorte de ancianos seguidos prospectivamente durante 5 años. Pacientes y métodos: 80 pacientes clínicamente estables; mediana de edad, 83 años (rango 69-97); 31,3% varones; 35% diabéticos; 83% hipertensos; reclutados aleatoriamente en consultas de Geriatría y Nefrología entre enero y abril de 2006 y seguidos durante 5 años. Medimos basalmente AU y creatinina en plasma y estimamos filtrado glomerular (FG) con fórmula MDRD abreviada. Asimismo, en los pacientes de Nefrología se midió la proteinuria mediante la recogida de orina de 24 horas, y en los vistos en Geriatría se estimó a partir del cociente proteínas (mg/dl)/creatinina (mg/dl) en primera orina de la mañana. Registramos edad, género, comorbilidad basal (Índice de Charlson), patologías cardiovasculares individualizadas, tratamientos y mortalidad. Estadística: SPSS15.0. Resultados: El AU basal presentaba una distribución normal y su mediana era de 5,85 mg/dl. No encontramos diferencias significativas en los niveles de AU según género, antecedentes de diabetes méllitus, hipertensión arterial, uso de diuréticos, cardiopatía isquémica, arteriopatía periférica o ictus. Los pacientes con antecedentes de insuficiencia cardíaca tenían AU significativamente mayor (7,00 ± 1,74 vs. 5,90 ± 1,71; p = 0,031). 41 pacientes (15 varones y 26 mujeres) fallecieron: 15 por deterioro en el estado general; 8 por infecciones; 4 por ictus; 4 por tumores; 3 por causas cardiovasculares; 2 por complicaciones de fracturas y 5 por causas desconocidas. Los pacientes con AU superior a la mediana tenían un FG significativamente menor y una mortalidad a los 5 años más elevada. En el análisis de Cox para mortalidad global (variables independientes: edad, género, Charlson, antecedentes de insuficiencia cardíaca, AU, creatinina, proteinuria y filtrado glomerular-MDRD) sólo los niveles de AU (riesgo relativo: 1,35; 1,17-1,56, p = 0,000) se asociaban de forma independiente a la mortalidad. Conclusiones: en nuestro estudio, los niveles de AU se muestran como factor de riesgo independiente de mortalidad en ancianos.

Introduction: There is growing evidence of the role of serum uric acid (SUA) as a risk factor for cardiovascular and renal disease. We analysed the association between baseline SUA and overall mortality in a cohort of elderly patients followed prospectively for 5 years. Patients and Methods: Eighty clinically stable patients, median age 83 years (range 69-97), 31.3% men, 35% diabetics, 83% hypertensives were randomly recruited at Geriatrics and Nephrology visits between January and April 2006 and followed for 5 years. We measured baseline SUA and serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with MDRD abbreviated. In Nephrology Department patients, we measured proteinuria in 24-hour urine and in Geriatrics department patients we measured proteinuria (mg/dl)/creatinine (mg/dl) in urine (first morning urine). Predictive variables were: baseline SUA and plasma creatinine; estimated GFR (abbreviated MDRD formula); and we recorded age, gender, baseline comorbidity (Charlson index), individualised cardiovascular treatment and mortality. Statistical analysis: SPSS15.0. Results: baseline SUA was normally distributed and its median was 5.85mg/dl. We found no significant differences in levels of SUA by gender, history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, diuretic drug use, heart disease, peripheral arterial disease or stroke. Patients with a history of heart failure had significantly higher SUA (7.00±1.74 vs 5.90±1.71, P=.031). Some 41 deaths occurred during follow-up (15 men and 26 women): 15 due to general deterioration, 8 due to infections, 4 due to stroke, 4 due to tumours, 3 due to cardiovascular disease, 2 due to complications of fractures and 5 due to unknown causes. Patients with SUA higher than the median had significantly lower GFR and higher mortality at 5 years. In the Cox analysis for overall mortality [independent variables: age, gender, Charlson Index, history of heart failure, SUA, creatinine, proteinuria and GFR (MDRD)] only SUA levels (HR: 1.35; 1.17-1.56 P=.000) were independently associated with mortality. Conclusions: In our study, levels of SUA are an independent risk factor for mortality in elderly patients.

INTRODUCTION

Uric acid (UA), a waste product of purine metabolism, is degraded by urate oxidase (uricase) to allantoin, which is freely eliminated in urine. One of the consequences of the absence of uricase in humans is the appearance of higher levels of UA in humans than in other species. It may even reach plasma UA concentrations fifty times higher than in other mammals. This condition, far from being a drawback, has been postulated to be an evolutionary advance related to the protective ability of UA against oxidative damage of free radicals.1,2

Hyperuricaemia is generally defined by UA levels >6.5mg/dl or 7mg/dl in men and >6mg/dl in women.3

Although recent epidemiological studies have focused on gout, which has been increasing in prevalence particularly among elderly individuals, the studies suggest that the incidence of hyperuricaemia has also increased during this time.4

In addition to the role of UA in the onset of rheumatism and gout, it has been postulated for some time that it is a possible determinant of the onset of hypertension (AHT), diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease (CKD).2,5

In recent years, there has been growing evidence of a relationship between high levels of UA in blood and renal and cardiovascular disease, endothelial lesions being the proposed pathogenic mechanism.2,6

Prospective epidemiological studies have shown the association between baseline levels of UA and the incidence of CKD (with increasing risk as UA levels increase).7,8

Regarding cardiovascular comorbidity, some studies found an association between UA and increased risk of heart attacks and coronary ischaemic strokes. However, other studies have not confirmed these results in multivariate analyses.2

On the other hand, some studies have shown that UA levels behave as a risk factor for both cardiovascular and overall mortality.9

In this study, we analysed the role of UA as an overall mortality marker in a cohort of elderly patients monitored for a period of 5 years. We also examined the association between baseline UA levels and cardiovascular history, the use of diuretics and renal function (RF).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was performed by analysing 5-year outcomes for a cohort of patients included in a study of elderly patients with CKD10,11,12 at the General Hospital of Segovia. Patients were recruited randomly while they visited the Geriatrics and General Nephrology departments during the period January-April 2006. Patients were in a period of clinical stability when they were selected and were monitored prospectively for 5 years (re-evaluation between January-April 2011). These patients had a mean age of 82.4±6 years (range 69-97 years) at baseline recruitment. Of these, 68.8% were women, 82.5% had histories of AHT, 35% were diabetic, 19.5% had histories of heart failure (HF), 15% had histories of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and 68.4% were receiving diuretic therapy.

Laboratory analysis

A baseline analysis was performed one week before patients attended scheduled visits at the Geriatrics and Nephrology departments. According to the standard procedures of our hospital's laboratory, we measured creatinine, UA, albumin, cholesterol and triglycerides in venous blood. We also analysed creatinine and proteinuria in 24-hour urine (Nephrology visits) or in first morning urine (Geriatrics visits).

Methods

This was a prospective observational study. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated with the abbreviated MDRD formula.13 Based on the median baseline UA, we established two study groups: Group 1 consisting of 40 patients with UA <5.85mg/dl, and group 2 consisting of 40 patients with UA >5.85mg/dl. We also examined the possible association between high levels of UA (P75) and demographic characteristics, RF and mortality.

After five years, we analysed mortality according to study group.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 15.0 program. Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation, or median and percentiles. Comparison of means was made with the Student's t-test and comparison of proportions with the chi-squared test. To analyse the simultaneous effect of several variables on mortality, we used a Cox analysis.

RESULTS

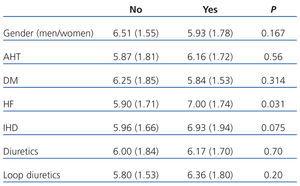

UA showed a normal distribution. Mean baseline levels of UA were 6.11±1.7mg/dl (range 2.8-11) and their median was 5.85mg/dl (P25=4.90mg/dl, P75=7.07mg/dl). Regarding the use of diuretics, 42.6% used loop diuretics and 29.5% used thiazides. Potassium-sparing diuretics were the least prescribed, at a rate of 11.5%. Table 1 shows the association between uric acid levels and gender, cardiovascular history and use of diuretics. Patients with histories of HF had significantly higher levels of UA (7.00±1.74mg/dl vs 5.90±1.71mg/dl, P=.031).

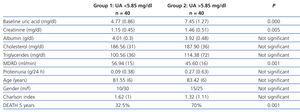

Table 2 shows the comparison between demographic characteristics, RF parameters, comorbidity and mortality at 5 years, according to median UA. Patients with UA higher than the median had significantly lower GFR and higher mortality at 5 years.

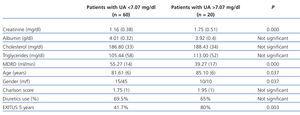

Twenty patients had UA greater than P75 (7.07mg/dl). Table 3 compares the variables according to this percentile.

There were no patients lost to follow-up that were not due to death.

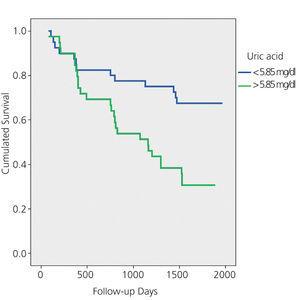

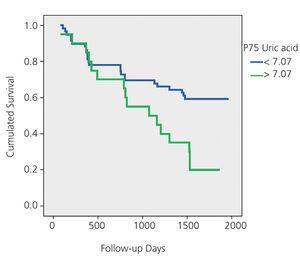

Overall, 41 patients died during the 5-year follow-up: 15 due to general deterioration, 8 due to infections, 4 due to stroke, 4 due to tumours, 3 due to cardiovascular problems, 2 due to fracture complications and 5 due to unknown reasons. In the multivariate Cox analysis, the only predictor of overall mortality after adjusting for age, gender, Charlson score, history of HF, use of diuretic and creatinine, presence of proteinuria and GFR-MDRD was UA level (mg/dl) (relative risk 1.35; 1.17-1.56; P=.000). Figures 1A and 1B show the Kaplan-Meier mortality curves according to the median uric acid and P75. Both figures show significantly higher mortality in patients with UA greater than P50 and P75.

DISCUSSION

Overall mortality in the patient group with UA levels higher than the median was significantly higher. Moreover, if we analyse patients with UA levels >P75 (7.07mg/dl), their mortality increases even further, reaching 80%, results that are consistent with other recent studies.9

In this cohort of longer-lived patients, the most frequent cause of mortality was progressive deterioration rather than cardiovascular disease, and baseline UA levels were found to be the only predictors of mortality in the Cox analysis.

Hyperuricaemia has been linked to various diseases in humans.4 Gout is a disease that predominantly affects men, with an increase in prevalence in both genders as age increases. In our study, men also had higher levels of UA, although these differences were not significant, which may be due to the fact that we treated postmenopausal women in whom estrogenic activity had ceased.14

CKD has been associated with hyperuricaemia.2 In experimental studies in rats with hyperuricaemia, renal lesions included afferent arteriolopathy, mild interstitial fibrosis, glomerular hypertrophy and/or glomerulosclerosis.15 We also found in our study that elderly patients with greater levels of UA had significantly worse RF. This association may be valid in both directions, that is, the high levels of UA may be explained by renal ischaemia and reduced RF, and/or reduced GFR in patients with higher levels of UA may be due to the direct toxic effects of UA.

Diuretics, widely used to treat AHT with the additional benefit of preventing HF episodes,16 increase UA by stimulating the reabsorption of sodium and urate in the proximal tubule.3 Moreover, the increase in UA has also been observed in conditions that are accompanied by hypoxia (obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive HF).17,18 Leyva et al first studied UA concentrations in patients with chronic HF and found an inverse relationship between UA levels and oxygenation, suggesting that damage from oxidative metabolism may play a role in the pathogenesis of HF.19 In the SHEP study, diuretics were demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular mortality in the elderly. However, a recent subanalysis found that cardioprotection was lower in those patients who had high levels of UA.20

In our study, we found that UA levels were similar among those who received diuretics and those who did not. Moreover, elderly patients with histories of HF, who generally require higher doses of diuretics, had significantly greater levels of UA. It is therefore conceivable that the increase in UA levels in elderly patients with histories of HF is showing the effect of a local ischaemia rather than the increase associated with diuretics. Similarly, patients with history of IHD have higher levels of UA, although in this case it was not statistically significant, possibly due to the low number of patients who had this disease.

Lastly, ischaemia determines an increase in xanthine oxidase, which leads to an increase in UA levels.3 Treatment with xanthine oxidase inhibitors, such as allopurinol, has shown to reduce cardiovascular complications after coronary bypass and in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.21 Recently, Goicoechea et al found that treatment with allopurinol in patients with chronic renal failure reduced the decline in RF.22

With the data from our study, we cannot confirm that there is a causal relationship between high levels of UA and mortality. A step forward in our study would have been to confirm whether the reduction in UA levels with allopurinol, or more recently with febuxostat (a new inhibitor of the xanthine oxidase),23 contributes to reduced mortality in these patients.

An important prognostic factor of morbidity and mortality is the presence of proteinuria.24,25 In our follow-up study of RF in the elderly, the presence of proteinuria at 36 months was an independent factor of mortality.12 This did not occur in our analysis at five years, either proteinuria is included in the model as a qualitative variable (yes/no) or if its numerical value is used. This may be explained by the lack of proteinuria in the baseline sample and by the fact that the patients with higher proteinuria died in the first years of follow-up.

In conclusion, our data show that UA is an independent risk factor for overall mortality.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Table 1. Baseline levels of uric acid (mg/dl) according to gender, cardiovascular history and use of diuretics

Table 2. Comparison of variables according to the median uric acid (5.85mg/dl)

Table 3. Comparison of variables according to P75 of uric acid (7.07mg/dl)

Figure 1A. Kaplan-Meier mortality curve according to the median uric acid (P50)

Figure 1B. Kaplan-Meier mortality curve according to P75 of uric acid (P50)