To the Editor:

Renal transplantation in patients with sickle cell anaemia has been performed successfully in recent decades;1,2 however, complications due to vaso-occlusive phenomena are common and may lead to graft loss.3 The presence of procoagulant properties in patients with sickle cell anaemia is well known and this results in a prothrombotic state, a risk factor for kidney graft survival, in which thrombosis accounts for 2%-7% graft loss.

There are some alternative treatments for preventing these thrombotic phenomena. One is to maintain haemoglobin A (HbA) levels close to 85%-90% of the total, preoxygenation with FiO2 at 40% for 48 hours after transplantation and avoiding periods of dehydration, hypoxia and acidosis.1,4

In this article, we report the case of a patient with a history of sickle cell anaemia who, following renal transplantation, presented vaso-occlusive crisis and acute humoural rejection of the graft and was successfully treated with exchange transfusion and plasmapheresis.

CASE REPORT

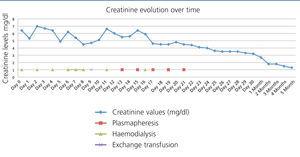

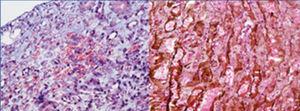

A 37-year-old black female with a history of sickle cell anaemia and end-stage chronic kidney failure, on haemodialysis for 6 years. She previously presented several episodes of sickle cell crises requiring multiple transfusions. In November 2010, she received a kidney transplant from a deceased donor, sharing a DR and an A, with a cold ischaemia time of 15 hours. Induction with alemtuzumab and methylprednisolone boluses was performed. During the intraoperative period, the patient showed low blood pressure, and required dopamine. The kidney graft perfusion was slow, with recovery during surgery. Postoperatively, the patient became anuric with an increase in nitrogen (Figure 1) and metabolic acidosis. Peripheral blood smear reported hypochromia, anisocytosis, microcytosis, target cells and high density lipoproteins 677, leukocytes 17 800, neutrophils 90%, lymphocytes 8%, haemoglobin 7.1, haematocrit 21%, platelets 179 000, corrected reticulocytes 5.2%. A Doppler of the graft reported good vascular perfusion but high resistance indexes. Vaso-occlusive crisis of the graft was suspected and management began with transfusions, hydroxyurea and haemodialysis. On the fifth day, biopsy was performed on the kidney graft (Figure 2); the major findings observed were infarction areas in peritubular capillaries with presence of neutrophils and erythrocyte entrapment, some with sickle cell aspect and C4d positive in 100% of the peritubular capillaries. With these findings, a diagnosis of acute humoural rejection and graft sickle cell crisis was made; treatment was performed with pulses of methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, tacrolimus, mycophenolate and exchange transfusion, the latter as sickle cell crisis management. Ten days after transplantation, improvement in renal function was observed and renal replacement therapy was suspended. The last creatinine control, four months later, was of 1.3mg/dl.

DISCUSSION

Sickle cell anaemia is a haemoglobinopathy that is commonly found in patients of African American origin,5 with an incidence of about 10%. It is caused by the replacement of valine by glutamic acid at position 6 of the beta chain in haemoglobin.6

Kidney graft losses in patients with sickle cell anaemia were observed as early as 2-6 weeks after transplantation. One study found that 35% of these patients had graft loss, of which 45% was secondary to rejection, 10% due to sickle cell crisis and 45% due to death.1 In other large series a one-year survival rate of 67%7 is reported, which suggests that vaso-occlusive crises and/or thrombosis may also be responsible for kidney graft losses.1

In renal transplanted patients with a history of sickle cell anaemia, kidney graft is susceptible to develop polymerisation of HbS and morphological alteration of erythrocytes.1 The pathogenesis of vascular occlusion is complex and multifactorial, the main associated factors being hypoxia, acidosis and low flow occurring in the peritransplant period; this initiates the activation of the endothelium with release of vasoactive products, increased leukocyte adhesion and higher procoagulant activity, which leads to an inflammatory response and vascular occlusion.1

This response typically comes within hours or days of renal transplantation and it may be another form of endothelial damage, with rejection being a secondary complication of said damage, rather than a primary event1; but there are reports suggesting that a mild to moderate rejection may lead to reduced oxygen levels and therefore an increase in the malformation of erythrocytes in renal microcirculation.8

This case report highlights the importance of vaso-occlusive crisis as a risk factor for early kidney graft loss in patients with sickle cell anaemia. In our population, it is common to find patients with this component, whether as sickle cell trait or its full form. For this reason, good clinical history knowledge in African-American patients and avoiding preventable prothrombotic events, such as periods of prolonged cold ischaemia, dehydration, hypoxia and acidosis during renal transplantation could be important measures for reducing early graft loss. Once the graft vaso-occlusive crisis occurs, it is necessary to initiate aggressive treatment in which multiple transfusions of erythrocytes and exchange transfusion should be considered to prevent graft ischaemia. In addition, the locating and treatment of rejection, which is common in this group of patients, is important in preventing its loss.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this article.

Figure 1. Creatinine values over time after renal transplant and days in which plasmapheresis (days 13, 15, 17, 19, 21), haemodialysis (days 0, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 16) and exchange transfusion (day 9) were received

Figure 2. Renal biopsy study