Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autoinflammatory and genetic disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and/or polyserositis (peritonitis, pleurisy, and arthritis). Mutations in the MEFV (Mediterranean FeVer) gene, which is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, result in impaired pyrin production and uncontrolled inflammation by proinflammatory cytokines. One of the most common complications of FMF is secondary amyloidosis of the kidneys. However, much less commonly, it is reported to be associated with various types of glomerulonephritis, such as mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.1 This article presents a patient with FMF whose renal biopsy findings were consistent with minimal change disease (MCD).

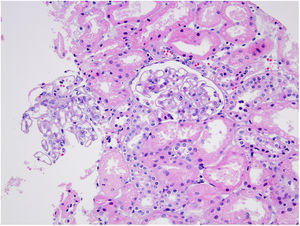

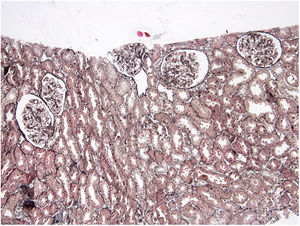

Case reportA 30-year-old female patient was diagnosed with FMF (with heterozygous polymorphism R202Q and heterozygous mutation M680I) six years ago after investigations for abdominal pain and febrile episodes. Treatment with colchicum dispert was started, but the patient never took it regularly. The patient was referred to our outpatient clinic complaining of extensive edema that had suddenly appeared ten days ago. On admission, her vital signs were stable. Physical examination revealed rales at the base of both lungs, diffuse edema of the lower extremities, palms, and abdominal wall, and ascites in the abdomen. Laboratory tests are listed in Table 1. Urinalysis revealed ++++ protein, fat cylinders, and oval fat bodies. Daily protein excretion was 17,000mg (reference range: 0–150mg/day). Renal ultrasonography was within the normal range. Serum antinuclear antibodies, antidouble-stranded DNA antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies were negative. Complement levels were within the normal range. Serum and urine electrophoresis studies revealed no evidence of monoclonal gammopathy or light chain disease. No compatible findings were noted on rectal biopsy, which was performed with a provisional diagnosis of secondary amyloidosis. Edema was controlled with diuretic therapy. In addition, colchicum dispert 1.5mg/day and ramipril 5mg/day were started. Percutaneous renal biopsy was performed to clarify the etiology of the massive proteinuria. Light microscopic examination revealed no pathologic findings, and Congo red and immunofluorescence staining were negative (Figs. 1 and 2). The biopsy findings were considered compatible with MCD. Possible secondary causes were excluded, and oral treatment with 1mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone was started. However, despite 16 weeks of treatment, remission was not achieved. With the diagnosis of steroid-resistant MCD and after reexamination of other causes of nephrotic syndrome, treatment was switched to cyclosporine-A (4mg/kg/day) and the glucocorticoid dose was gradually tapered. During 4-month follow-up period, proteinuria decreased to 240mg/day, and remission was achieved (Table 1).

Laboratory results at the time of admission and the end of cyclosporine treatment.

| Reference rates | The time of admission | The end of cyclosporine treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.7–15.5 | 13.1 | 13.4 |

| White blood cell (mL/mm3) | 4–10 | 5.6 | 8.45 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 17–43 | 20 | 22.8 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.66–1.09 | 0.58 | 0.53 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 135–145 | 136 | 142 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.5–5.0 | 4.36 | 4.47 |

| Calcium (mEq/L) | 8.6–10.2 | 8.61 | 8.72 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.6–8.3 | 4.36 | 6.34 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5–5.5 | 1.14 | 4.2 |

| Microalbumin (mg/day) | 0–30 | 8866 | 90 |

| Daily protein excretion (mg/day) | 0–150 | 17,000 | 241 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm3/h) | 0–25 | 88 | 23 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 200–393 | 891 | 329 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0–5 | 18 | 3 |

| C3 (g/L) | 0.79–1.52 | 1.21 | 1.19 |

| C4 (g/L) | 0.16–0.38 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0–100 | 358 | 130 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 0–150 | 249 | 195 |

Abbreviations: C: complement; LDL: low density lipoprotein.

The most important and well-known renal complication in FMF is renal amyloidosis, which causes a nephrotic syndrome clinic. However, the purpose of this article is to draw attention to the fact that the disease may be much less commonly associated with non-amyloid renal involvement. In a large series of 2436 FMF patients, 12.9% of cases had biopsy-proven amyloidosis, and 0.8% of cases had non-amyloid glomerular disease.2 Non-amyloid diagnoses included mesangial-capillary glomerulonephritis, mesangial-proliferative glomerulonephritis, diffuse endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulonephritis.1,2 To our knowledge, our case is the first case of FMF-related steroid-resistant MCD described in the literature.

The FMF-related inflammation may be described as chronic and recurrent in addition to being dysregulated.3 This impaired inflammatory response in FMF patients may initiate or facilitate immunological damage, a common cause of glomerulonephritis.4 Hence, a possible link between FMF and MCD could be dysregulation of the immune system. The mutant pyrin cannot control inflammation in FMF patients, and the systemic inflammatory response gets out of control due to the activation of interleukin-1b and nuclear factor kappa.3 During autoinflammatory attacks, levels of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 increase and with colchicine treatment, levels of IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha decrease.5 These evidence may indicate the involvement of cellular immunity in the pathology of FMF patients. Although the etiopathogenesis of MCD is not clear, it is known that cellular immunity is damaged. A “permeability factor” produced by T cells increases the protein permeability of the glomerular filtration barrier, particularly by altering podocyte morphology.6 For example, a possible permeability factor is interleukin-17, and levels elevated during disease have been shown to normalize in remission.7 Based on these points, it can be assumed that a factor arising from uncontrolled inflammatory cascades damaged the podocyte morphology in our case. Of course, much more data is needed to elucidate these unknown relationships. Colchicine is the main pharmaceutical agent used in the treatment of FMF to prevent inflammatory episodes and the development of amyloidosis. Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is thought to affect chemotaxis by influencing microtubule function.8 The literature suggests a possible link between FMF and glomerulonephritis, but there is insufficient experience regarding optimal treatment and prognosis. Limited data suggest that uncontrolled colchicine therapy may also be associated with the development of non-amyloid renal lesions and that colchicine treatment alone may actually improve the situation.9 The case presented here is a patient who never received regular colchicine treatment for six years after diagnosis. Although colchicine treatment was started immediately after hospitalization and continued throughout steroid treatment, no response was obtained. However, the follow-up in our case did not fully allow for the assessment of response to colchicine therapy.

As a result, patients with FMF may exhibit a variety of renal disorders. Although renal amyloidosis comes to mind first, non-amyloid pathologies may also rarely develop in these patients. Colchicine may have a preventive and therapeutic effect for non-amyloid glomerulonephritis as well as for renal amyloidosis. On the other hand, it is also clear that some of the non-amyloid glomerulonephritis cases will require specific glomerulonephritis treatment as in our case. Considering this possibility in cases of proteinuric FMF may be beneficial in the short and long term on a patient basis. At this point, the accumulated data can improve the management of patients.

AuthorshipEach author has contributed substantially to the research, preparation and production of the paper and approves of its submission to the Journal.

All authors: Final approval of manuscript.

Financial supportNone.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest.