Dear Editor,

Postpartum hemolytic uremic syndrome (PHUS), first described in 1968, is defined as a thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) typically following a normal delivery after a symptom-free interval (mean 26.6±35 days).1 It usually occurs in primigravida with the mean age of 27.0±6 years and preeclampsia is historically associated with the disease.1,2 The involvement of extrarenal vascular beds in PHUS has been less reported. Here we report for the first time a severe case of PHUS complicated by pancreatic necrosis, bilateral visual loss due to central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

A 20-year-old primigravid was admitted for edema and headache when she was 34 weeks pregnant. On presentation her blood pressure (BP) was 180/115 mmHg and moderate edema on face was noted. Initial investigations showed 3+ proteinuria and normal serum creatinine (Scr) concentration. The diagnosis of preeclampsia was established and a cesarean section was performed in the 35th week of gestation.

Nine days later, the patient complained of oliguria, nausea with BP of 175/105 mmHg. Laboratory tests revealed hemolytic anemia, with hemoglobin of 81 g/L, serum haptoglobin <0.2 g/L, and schistocytes shown in peripheral blood smear. Platelets (Plt) were markedly reduced at 41×109/L and an acute rise of Scr to 463.2 μmol/L showed acute renal failure. The immunologic studies revealed negative anti nuclear antibody and Coomb’s tests. Under suspicion of PHUS, antihypertensives, aspirin and furosemide were commenced on the 1st day of presentation and renal biopsy was performed on day 2.

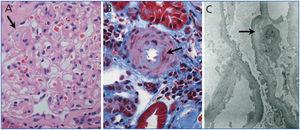

The patient complained of left-upper abdominal pain after renal biopsy and developed a sudden bilateral painless visual loss. The subcutaneous bleeding over her upper arms was noted and she rapidly developed anuria, dyspnea, confusion, hypotension with BP of 70/50 mmHg. The ultrasound scan excluded the existence of perinephric / subcapsular hematoma caused by renal biopsy. The fundus exam revealed bilateral CRAO. Laboratory tests on day 3 showed elevated serum amylase, lipase and Scr up to 625μmol/L, Plt down to 12.2×109/L. The level of fibrinogen decreased to 3.82μmol/L with delaying activated partial thromboplastin time and positive D-dimer. Computed tomography scan confirmed pancreatic necrosis. Renal pathology showed thickened glomerular capillary walls with subendothelial edematous expansion that forming double contouring and renal arteriolar intimal expansion with fibrin exudation on the arteriolar wall (Figure 1). Based on these findings, the diagnosis of PHUS complicated by pancreatic necrosis, CRAO and DIC was established.

She was treated with pulse methylprednisolone 500mg/d and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 20g/d for 3 days. Meanwhile, plasma exchange (PE) with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) infusion and CRRT were initiated. Anticoagulant therapy for DIC and CRAO were also carried out. On day 15, she was improved significantly and the urinary output increased whereas the bilateral vision improved only slightly and hyperglycemia became noted. On review after 6 months of onset, she remained bilateral visual loss, elevated blood glucose and Scr when hemodialysis and subcutaneous injection of insulin were suspended. These showed the irreversible visual impairment, secondary diabetes mellitus dependent on insulin and the progression to CRF.

HUS and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), collectively referred to as TMAs, occur with increased frequency during pregnancy or the postpartum period. These two disorders are considered by many to be manifestations of the same disease process; however, others consider HUS and TTP to be distinct entities.3 Since TTP and HUS share many overlapping features, distinguishing the two disorders may be difficult.4 As in the case we showed, the patient developed TMA with disturbance of consciousness that seemed to suggest TTP; however, the prominent renal insufficiency and the lack of diffused thrombi in renal tissue might support PHUS rather than TTP. Another differential diagnosis should be included in this case is hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome (HELLP syndrome). HELLP, usually associated with preeclampsia is more common in multiparous women and approximately 70% of HELLP occur prior to term, with the remainder usually occurring within 48 hours after delivery.5 Patients with HELLP frequently present with severe right upper quadrant pain. Based on these characteristics of HELLP, we prefer to diagnose our case as PHUS.

Although the pathogenesis of PHUS is unknown, the previous cases reported2,6,7 and the case presented here demonstrated preeclampsia could possibly trigger PHUS by causing platelet aggregation, deposition of microthrombi and occlusions in the microvasculature of the kidney, resulting in acute renal failure. The deficiency of ADAMTS-13, a metalloprotease that cleaves ultra-large von Willebrand factor (VWF) multimers observed in PHUS8 which suggest PHUS may be also associated with ADAMTS-13 deficiency. Recent studies revealed alternative complement 3 convertase dysregulation were detected in most PHUS patients suggesting PHUS was probably associated with complement gene mutation.9

Multiple organ involvement such as pancreas and ocular structures were reported in non-pregnancy-related HSP,10,11 whereas PHUS involving extrarenal vascular beds has been less reported so far except central nervous system and liver damage.12,13 Does this mean PHUS have a better prognosis than non-pregnancy HUS? The case we described here developed multiple organ damage such as pancreatic necrosis, CRAO, DIC and progressed to secondary diabetes mellitus, bilateral visual loss and CRF eventually. The severe complications of pancreatic necrosis and CRAO might be the manifestations of TMA in PHUS, but might be more likely induced by DIC in this patient. Anyway, this case suggests PHUS could also involve multiple organ dysfunctions and result in bad outcomes even if the appropriate treatments have been given without delay.

The renal pathology in HUS is characterized by glomerular capillary subendothelial expansion, arteriolar fibrinoid necrosis, arterial edematous intimal expansion and vascular thrombosis. The preceding etiologic conditions of HUS and the histological findings appeared not to be related to each other.14 Our case showed typical subendothelial edematous expansion and renal arteriolar intimal expansion with fibrin exudation which supported renal microangiopathy, but without diffused thrombi and fibrinoid necrosis in renal tissue which seemed to be inconsistent with the following development of multiple organ complications and the progression to CRF. This was considered to be due to the early performance of renal biopsy after the attack and the early pathological findings in PHUS presented here may be difficult to predict the disease development and poor prognosis.

In conclusion, pancreatic necrosis, CRAO and DIC were observed in PHUS. Although renal replacement therapy and PE with FFP infusion have improved the survival of PHUS significantly, multiple organ complications such as pancreatic necrosis, CRAO and DIC may cause severe sequelae and lead to a poor prognosis of PHUS.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Figure 1. Renal biopsy findings in postpartum hemolytic uremic syndrome