El síndrome de Goodpasture (SGP) es una rara entidad de base inmunológica, caracterizada por la asociación de una glomerulonefritis rápidamente progresiva (GNRP) y hemorragia alveolar en presencia de anticuerpos antimembrana basal. La afectación del sistema nervioso central (SNC) en el SGP es extremadamente infrecuente en ausencia de ANCA. Presentamos el caso de un paciente de 20 años que comenzó con una GNRP acompañada de esputos hemoptoicos y dos episodios de crisis convulsivas tónico-clónicas generalizadas, en presencia de elevados títulos de anticuerpos antimembrana basal glomerular (Ac-anti-MBG). Tras tratamiento inmunosupresor asociado con plasmaféresis, el paciente presentó descenso de los títulos de Ac-anti-MBG, así como mejoría de los síntomas neurológicos y respiratorios, aunque sin recuperación de la función renal, permaneciendo en programa de hemodiálisis. Veinte meses más tarde, con la enfermedad en remisión, el paciente recibió un trasplante renal de cadáver.

Goodpasture´s syndrome is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) and alveolar hemorrhage in the presence of anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies. Central nervous system involvement is highly unusual in the absence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. We report the case of a 20-year-old man with RPGN accompanied by bloody sputum, tonic-clonic seizure and high titers of anti-GBM antibody. After treatment with immunosuppressants and plasmapheresis, the patient showed reduced anti-GBM antibody titers and improved neurologic and respiratory symptoms, but renal failure persisted, requiring hemodialysis. Twenty months later, with the disease in remission, he underwent deceased-donor renal transplantation.

INTRODUCTION

Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody disease is an immunological disorder characterized by the presence of circulating antibodies that act directly against an intrinsic antigen of the glomerular basement membrane, provoking a rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN).

Goodpasture’s syndrome (GPS) has generally been used as a synonym for anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody disease, which is characterized by the association of RPGN and alveolar haemorrhage in the presence of anti-basement membrane antibodies (anti-BM Ab). Damage to the central nervous system (CNS) from GPS is quite rare in the absence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and has only been described in 4 cases in the medical literature.1-4

Here, we present the case of a 20-year-old patient who started out with RPGN, accompanied by haemoptoic sputum and two episodes of generalized tonic-clonic convulsive seizures, with high anti-BM Ab titres.

Clinical case

20-year old man, smoker and former cocaine and cannabis user, who was admitted to the hospital with macroscopic haematuria and acute oliguric renal failure (AORF). 12 days before admission, the patient presented with asthenia, anorexia, vomiting, and dysuria, for which he visited a general practitioner who diagnosed him with a urinary infection and prescribed ciprofloxacin treatment. Four days later, he referred a fever of 38ºC, macroscopic haematuria, and a subjective decrease in diuresis.

The physical examination revealed the following: blood pressure: 140/90 mmHg, temperature: 37 ºC. Deteriorated general health, pallor of skin and mucosae, and bibasal hypoventilation. Upon admission, AORF was observed, requiring haemodialysis during the first 24 hours. 48 hours later, the patient presented haemoptoic sputum, followed by two episodes of generalised tonic-clonic convulsive seizures.

The laboratory results from the time of admission revealed: haematocrit, 25.5%, haemoglobin, 8.9 g/L, leukocytes, 16,700/mm3, platelets, 344,000/mm3, ESR, 96 mm/h, creatinine, 11.8 mg/dL, BUN, 90 mg/dL, glucose, 97 mg/dL, total protein, 5.3 g/dL, albumin, 4.5 g/dL, calcium, 8.2 mg/dL, sodium, 134 mEq/L, potassium, 5.2 mEq/L. Proteinogram, immunoglobulins, and kappa/lambda light chains were normal. Serology for hepatotropic virus, HIV, and liver function tests revealed no abnormalities. Blood and urine toxin screens, including tests for cocaine metabolites, were negative. The immunological study, which consisted of ANA, ANCA, antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin Ab, and complement levels were all negative. However, anti-BM Ab were positive (72.5 ug/mL, normal range <10 U). The urine analysis (24 hrs) revealed a proteinuria of 850 mg. An intense haematuria in the urine sediments was also observed. The chest radiograph showed bilateral alveolar/interstitial infiltrates, indicative of alveolar haemorrhage. The renal ultrasound revealed normal sized kidneys with increased cortical echogenicity. The electroencephalogram, cerebral magnetic nuclear resonance (NMR) and the cerebral angio-NMR were all normal.

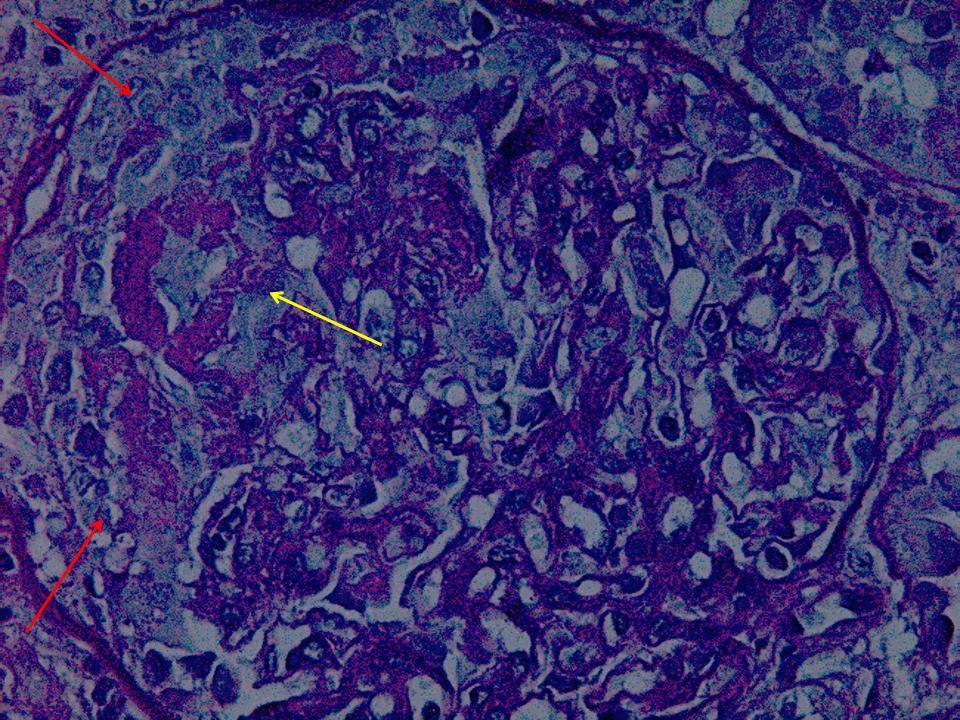

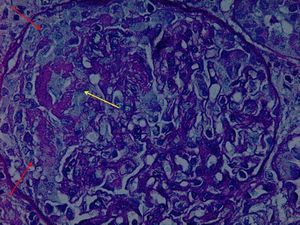

Four days after the patient was admitted, we performed a percoetaneous renal biopsy, in which we observed an extracapillary glomerulonephritis (100% of crescents), with collapsed glomerular tufts, areas of fibrinoid necrosis, moderate inflammatory infiltration and incipient interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (Figure 1). The immunofluorescence scan showed linear deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG) along the glomerular basement membrane.

The patient was diagnosed with GPS associated with a probable ANCA negative CNS vasculitis. Upon admission, the patient was treated with 3 500mg boluses of methylprednisolone for 3 consecutive days. Subsequently, oral cyclophosphamide was added in a daily dose of 1.5 mg/kg along with 15 sessions of plasmapheresis. Furthermore, the patient received treatment with valproic acid. The respiratory and neurological symptoms disappeared with the prescribed treatment, but unfortunately, the renal function did not recover, and the patient remained on a haemodialysis program upon discharge.

Twenty five days after being admitted, the patient was discharged from the hospital with negative anti-BM Ab titres, allowing a slow reduction in the immunosuppressant treatment, with no indications of relapse. Cyclophosphamide was ended 3 months after admission, but the patient remained on low doses of steroids (2.5 mg/day) and on a haemodialysis program (Figure 2).

Subsequent evolution

Six months after being discharged, and after non-compliance for antihypertensive treatment, the patient was readmitted for a hypertensive emergency (blood pressure at 220/120 mmHg and a right temporal intraparenchymal haematoma that required surgical drainage). At this point, serial measurements of anti-BM Ab levels were negative, and in spite of the severity of the damage, the patient presented with no neurological deficit upon discharge.

Twenty months later, the patient received a kidney transplant from an organ donor, as well as immunosuppressant treatment with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. The kidney transplant has been satisfactory so far, and the patient has referred no recurrence of the disease (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

GPS is a rare immunological disorder characterized by the triad of RPGN, the presence of circulating anti-BM Ab, and pulmonary haemorrhage. Although genetic factors have been associated with an increased likelihood to develop this syndrome, other factors such as environmental exposure (viral infections, exposure to volatile hydrocarbons and tobacco smoke) could trigger the disease in predisposed individuals, particularly in those with underlying pulmonary lesions.5 Additionally, the consumption of cocaine has also been related to anti-BM Ab disease.6 Our patient was a smoker, as well as a previous cocaine user, factors that could have influenced in triggering the disease.

In 10 to 30% of cases, anti-BM Ab disease is associated with ANCA, and the majority of patients have low titres of anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO). This subgroup of patients probably presents a variant of associated vasculitis.7 However, although the exact cause of the development of ANCA in anti-BM Ab disease has not been clarified, some authors suggest that a polyclonal activation mechanism could be responsible.8

GPS is characterized by the presence of autoantibodies against the epitope of the alpha 3 chain of type IV collagen (alfa-3 [IV] NCI), labelled the Goodpasture antigen.9 Although this antigen has a wide distribution, it is primarily expressed in the glomerular and alveolar basement membranes, and less frequently in tubular, cochlear, retinal, and choroid plexus basement membranes.

Cerebral involvement in GPS is extremely rare in the absence of ANCA, and only 4 cases have been described in the medical literature.1-4 All of the cases that have been communicated presented with recurrent convulsive seizures related to cerebral vasculitis with or without haemoptysis. Rydel et al.1 described the first case of ANCA-negative cerebral vasculitis associated with GPS, demonstrating vasculitic infiltrates in the meningeal biopsy. Although cerebral and meningeal biopsies constitute the gold standard for the diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis, their use is currently limited to patients with doubtful diagnosis due to the aggressive nature of the procedure. Furthermore, in most of the described cases of GPS with cerebral involvement, the diagnoses of ANCA-negative cerebral vasculitis associated with GPS were performed based on the clinical presentation of the patient and the findings from imaging tests.2-4 Our patient started with RPGN requiring dialysis from the beginning, followed by pulmonary haemorrhage and two events of tonic-clonic convulsive seizures, together with elevated anti-BM Ab levels. The repeated ANCA measurements were negative, and other possible causes that could have triggered the convulsive seizures, such as metabolic disorders, drug deprivation-induced hypertensive seizures, etc. were excluded. Although the cerebral NMR came up normal in our patient, we cannot rule out that small vessel vasculitic lesions could have contributed to the cerebral damage that was caused. Indeed, cerebral NMR scans come up negative in as much as 35% of patients with cerebral vasculitis.10 Cerebral angiography was not performed because the neurological symptoms disappeared with the previously described treatment. Furthermore, we also observed an improvement in respiratory symptoms, although renal function never recovered. Levy et al. showed that renal insufficiency as estimated by plasma creatinine levels (>5.7 mg/dL) or the need for dialysis at the onset of the disease, as well as a percentage greater than 50% of crescents found in the renal biopsy, are all negative prognostic factors for the recovery of kidney function.11

Kidney transplants are possible to perform in this disease, although there does exist a risk of recurrence in the new organ, leading to the recommendation that at least a 6-month waiting period be necessary for the transplantation and only when anti-BM Ab titres are undetectable. This is a promising strategy in the majority of cases, as in our patient, who received an organ donor transplant 20 months later, presenting with a positive clinical evolution and no signs of recurrence of the disease.

Finally, we conclude that GPS with neurological involvement is extremely infrequent, especially with negative ANCA. Normal cerebral NMR findings do not exclude the possibility of small vessel cerebral vasculitis, requiring an aggressive and early diagnosis and treatment of GPS in order to improve the prognosis of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Eduardo Salido for his advice on renal pathology and review of the manuscript.

Figure 1. Extracapillary glomerulonephritis (red arrows) with centres of fibrinoid necrosis. Yellow arrow, PAS stain, 400x.

10237_108_8375_en_w4777103917table1_en.doc

Table 1. Data on the patient¿s evolution from the onset of GPS.

10237_108_8377_en_w4777103918fig2_en.ppt

Figure 2. Evolution of Anti-BM antibodies and renal function following the initiation of treatment with steroids, oral cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis